“The world thinks it’s difficult to combine meaningful current income with growth of capital, but we don’t agree and have proven otherwise,” declares David King, lead portfolio manager of the Columbia Flexible Capital Income Fund, which holds securities that offer the potential for income and price appreciation. His matter-of-fact tone exudes confidence without braggadocio, and the performance numbers back up his claim.

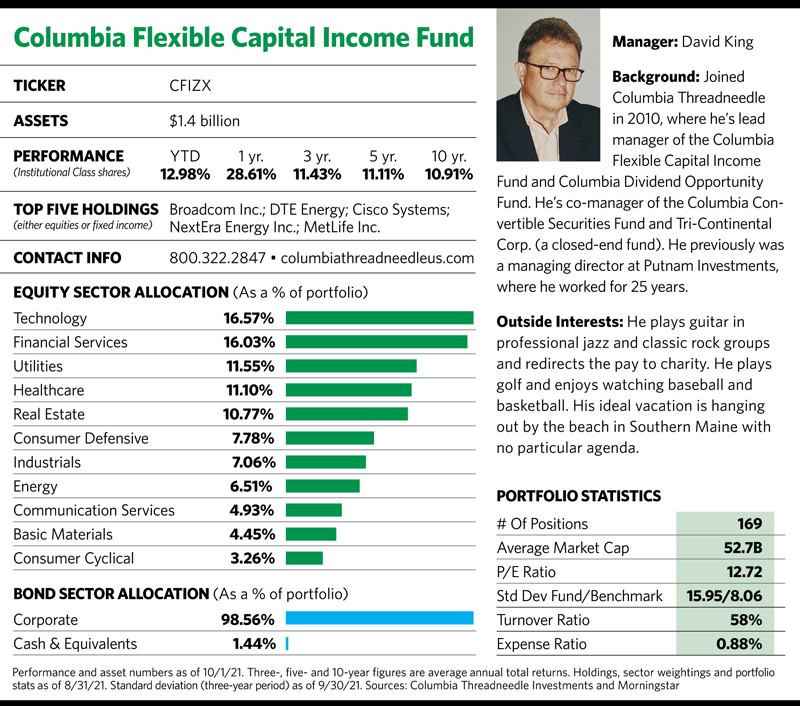

The fund has landed in the top quartile in Morningstar’s “Allocation—30% to 50% Equity” category in all of the measurable periods from year-to-date (as of October 1) through the past 10 years. The portfolio recently included roughly 170 holdings grouped into three main asset classes. Equities represented the largest category at about 45% of the portfolio, followed by bonds and convertible securities at 28% and 27%, respectively.

While the fund is included in an asset allocation-type category, King dismisses the notion that his fund is guided by asset-allocation concerns. Instead, he states that portfolio flexibility via securities selection is his game.

“The end idea of any investment is to get to a solution, and the mechanics are just the route to that,” King says. “We thought we could construct a portfolio that would have meaningful current yield with growth of capital. The consensus view has been that’s not possible in today’s low interest rate environment, or that it’s just very difficult. It’s made difficult because nearly everyone else who tries to do this does so through a top-down, asset-allocation lens.

“Our proposal is that you build it through securities,” he continues. “That’s what has enabled us to be the top-performing fund in total return in our Morningstar category in the past 10 years. And it’s one of the highest-yielding funds at the same time.”

The Columbia fund’s 10-year annualized return through October 1 was nearly 11%, and its trailing 12-month yield was 4.26%, according to Morningstar. King credits the fund’s success to the securities selection acumen of its three-member management team, which also includes Yan Jin and Grace Lee, along with what he describes as the strong collaborative culture at Columbia Threadneedle Investments, a Boston-based money manager with roughly $600 billion in assets under management.

“It’s easy for me to say everyone should go bottom up when they want to have income and growth, and another thing to do it because there are thousands of potential securities,” King explains. “That would be difficult except for all of the people [in Columbia’s investment research department] who will help us out who follow dividend-paying equities or bonds or areas such as REITs or other areas we might choose to find income in.”

Sometimes, he and his team know a particular company well enough that, for example, they need to look only at that company’s bonds, because the stock doesn’t pay a dividend. At other times, an analyst on Columbia’s research team might suggest a new bond that would be a good fit for the fund. Or maybe an equity analyst recommends an equity, but King’s team won’t buy that equity because it doesn’t pay a dividend. Instead, the company might have a convertible security or bond the firm can buy, so the team will confer with a credit analyst who covers the company.

“The unifying premise is that all of the securities we buy have a dividend or a coupon and they’re all denominated in U.S. dollars,” King says. “In our world of stock-paying dividends, converts, preferreds, REITs, MLPs, bank loans and bonds, we think these securities are more similar than different when you analyze them from the bottom up.

“It’s done bottom up as if there isn’t a meaningful difference between the stock of Verizon or the next junk bond deal being done,” he adds. “We think that philosophy is the extreme minority view.”

The fund’s two recent top holdings—Broadcom Inc., a maker of semiconductor and infrastructure software products, and DTE Energy, a diversified energy company—embody its flexible approach to securities selection. Both companies are covered by Columbia’s equity analysts, but the fund’s portfolio managers approach them differently.

“Broadcom has been a great stock that’s been a cheap, fairly unloved tech company that does acquisitions,” King says. “They did a software acquisition that people hated, but the stock is now about 300 points higher since then, and now people don’t hate it as much. Broadcom’s dividend growth has been excellent, and the yield is still superior. But we’ve sold some shares to keep the weighting contained.”

King notes that the fund holds DTE’s convertible preferred securities rather than its equity because the former offers more income. Elsewhere, he and his team have spotted a couple of interesting yield trends they believe have fallen through the cracks.

That includes convertible securities in the utilities sector that offer high yields. “They’re bond-like but they’re very safe,” King says, pointing to the substantial coupons offered by UGI Corp., a natural gas and electric power distributor, and South Jersey Industries, an energy services holding company.

The other yield trend King highlights is at companies offering a special dividend on top of their base dividend. This includes fund portfolio holdings such as hydrocarbon exploration company Pioneer Natural Resources, personal installment loan provider OneMain Financial and farm machinery maker Agco Corp.

“The concept of special dividends has been frowned on by Wall Street because a lot of this involved weak companies that were doing this to attract investors as a gimmick,” King explains. “But when a company like Pioneer with a strong investment-grade balance sheet does it, and where it’s a very cyclical business and we think the cycle is improving in energy, we look forward to achieving yields as high as 8% per annum from that common stock depending on its stock price. But it would be less if the stock goes up, which would still be good.”

All Of That Jazz

King has played guitar in rock and jazz bands for four decades, and for the past 15 years has played in a regular standing jazz band. “In an emotional intelligence sense, the process of playing jazz is just like running a portfolio, at least the way I do it,” he says, adding that playing a jazz number and running a portfolio both require some improvisation when it comes time to make small, midcourse corrections.

“The other people I deal with aren’t left-handed jazz musicians, so sometimes I have to readjust my brain and realize I’ve missed some important things that smart liner people know,” he says. “And other times I just know things that other people don’t know, and people ask how I know that but I can’t always say why.”

King says he and his team don’t worry about how much they should own in a particular sector; if they see something they like, they buy it. “It’s driven by the supply of things we can get that we like; it’s not driven by our view of the Fed or any sort of macro thinking,” King says. “It’s more of, ‘What’s out there and what can we do?’”

When the team discovers a big sector overweight in the portfolio, they’ll reduce it by selling some of each security in that sector. “We don’t decrease our overweight by selling [outright] something we like,” he explains. “We adjust our weightings within a sector.”

The Columbia fund’s seemingly free-form approach has delivered the performance goods, but Morningstar noted the fund’s credit risk profile is relatively high for its peer category. In addition, its Sharpe ratio is higher—and its standard deviation is higher—than the category average. Sharpe ratio measures reward-to-risk efficiency, and a higher value is better. Standard deviation gauges volatility by measuring dispersion around an average, and a lower value is better.

“There’s no question that we have a higher standard deviation than the category,” King acknowledges. “If you buy the average fund in this space, you get very low volatility and very mediocre returns. We’re OK with people getting a little more volatility, but we’re not talking about hair-raising risk. There’s standard deviation, but then there’s 10 years of history where you see a really bad year for us is like a mid-single-digit loss, while some of the good years have been north of 20% in total return.”

Since the fund launched in July 2011, it twice suffered annual losses in the 6% area. Its best year was 2019, when it posted a total return of 22.6%.

“This is my largest single asset holding,” King says. “The fund is designed for people like me who are later in their working career or retired and with a 15-year or more life expectancy. The point of the fund is there’s definitely some meaningful income, but it’s not intentionally at the expense of your capital, which we expect to grow.”