One of my least favorite market cliches is “healthy correction.” Why exactly is it ever good for your health to lose money? And how do we know when a market is “correct”? That said, if there is any such thing as a healthy correction, we might just have seen one in U.S. large-caps this month.

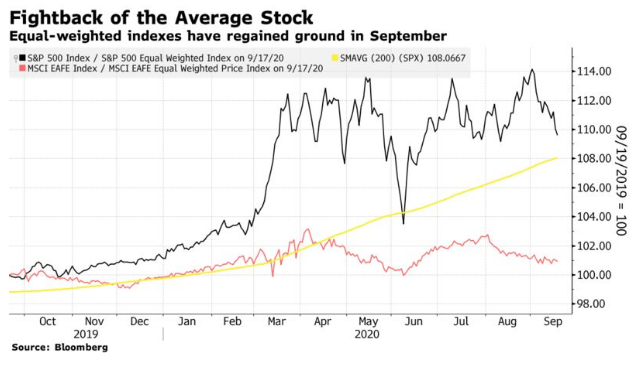

The rebound since the Covid scare reached its worst in March has been one of the most unbalanced and narrow rallies ever seen. The market cap-weighted version of the S&P 500 massively outperformed the equal-weighted version — or in other words, the average stock did far worse than the overall index. That was because gains were concentrated in a few big companies. That trend has been at least somewhat corrected in the last two weeks:

Note that the trend of outperformance by the cap-weighted index was briefly but dramatically interrupted in June. That was when the coronavirus appeared to be coming under control, just before it became clear that a second outbreak in the Sun Belt was forming. The phenomenon of investors pumping everything into a few big names thought to benefit from the pandemic, led by the tech players, has been central to creating such a narrow market.

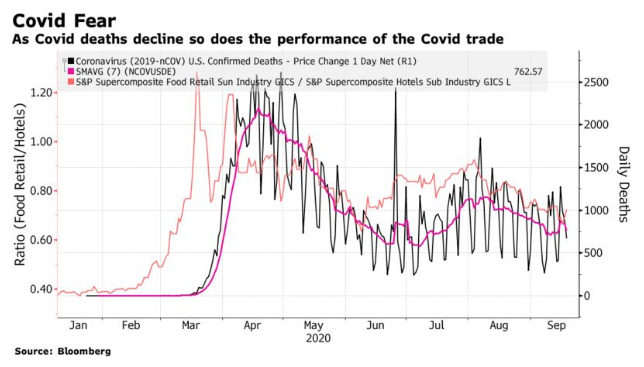

We can see this more clearly from a “pure” version of the Covid-fear trade, which shows how food retailers (thought to benefit) perform relative to hotels, resorts and cruise lines (plainly very much harmed). The following chart shows how this trade has performed, compared to the number of new Covid-19 deaths each day. Covid-fear is obviously reducing at present, which has meant that hotel stocks have regained ground on food retailers. The current death statistics don’t suggest the pandemic is over, but do indicate that it is less dangerous than once thought, so this makes sense:

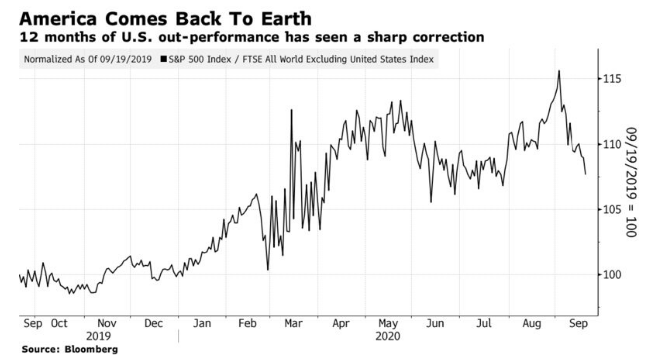

This isn’t just about the market narrowing. A number of other trends, all linked with the dominance of the FANG stocks, had already been brought to a point where they looked ready to collapse on themselves. And indeed, they are correcting. The U.S., as measured by the S&P 500, had massively outperformed the rest of the globe, as tracked by FTSE’s index for the world excluding the U.S., for the year so far. Corrections for the FANGs have brought a relative decline for the U.S.:

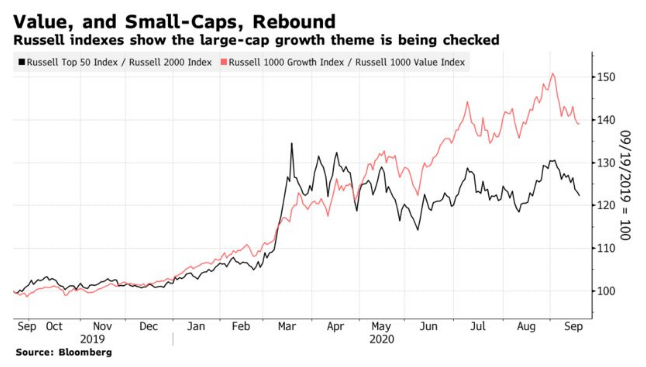

In a more muted way, the Russell indexes show that within the U.S. the strong outperformance by growth over value, and by mega-caps versus small-caps, has also been pegged back somewhat in September:

In all cases, the underlying trend in need of correction remains intact. The FANG stocks are still up massively for the year, and the rest of the world is not. The NYSE Fang+ index (which also includes American depositary receipts issued by some big Chinese internet names) has still outperformed the equal-weighted S&P 500 by an astonishing 74%. Logically, it is hard to see how this can be sustained:

So if the correction so far has been healthy, then by the same logic it would be healthier still for the correction to continue a while. If that involves investors coming to realize that the internet platforms will not be able to gobble up everyone else’s profits forever and a day, that would be healthy on a number of levels.

That said, the continuing move in volatility suggests that the greatest excess caused by speculation in call options has now worked its way through the system. The VIX index measures volatility by how much investors are prepared to pay to protect against future swings through the options market. Usually, the VIX will move in the opposite direction to the stock market. When equities are doing well, the options market shows less anxiety. In the last four weeks, there was first the sight of the S&P 500 spiking higher while the VIX also rose, and then in the last week gradual declines in both the stock market and the VIX.

The worst excesses from the options market, at least, have been corrected. And that is healthy.

Herd Mentality

Herd mentality is in the news, as well as herd immunity. Whatever its role in combating the pandemic, it has long played an important part in the world of investing. Professional investors are paid not to make the most money possible with the least risk, but to accumulate the most assets — which generally means doing a bit better than their peers. That makes big contrarian bets very dangerous to their careers, and creates an incentive to hug their benchmark. It’s often best expressed in terms of herd psychology; in a herd of antelope, it is safest to be in the middle, as it is those at the front or the back who are most likely to be attacked by lions.

Herding by fund managers, arguably exacerbated by the increasing importance of indexes and passive investments as competition, hasn’t improved performance for their clients. Usually, the brave contrarians who pick the least crowded stocks get rewarded with much better performance than those who stick with the herd. This year is a big exception. In the following chart, from BofA Securities Inc.’s quantitative equity strategist Savita Subramanian, the yellow bars show the performance of the 10 most overweight stocks among equity fund managers, while the blue lines show the performance of the 10 most shunned. Usually, there is good money to be made by betting against the crowded trade. This year has been very different:

According to Subramanian, the spread of 19.2% in favor of crowded over under-owned stocks is the strongest in a decade. So this is a market that is becoming narrower, and where it is harder than usual to make money by betting against the consensus. Subramanian also published a chart using the concept of “active share” — the proportion by which a fund’s portfolio differs from its benchmark. The higher the active share, the more fund managers are deviating from their index, and avoiding a herd mentality. A hugely influential paper published in 2006 by Martijn Cremers and Antti Petajisto suggested that higher active share was associated with stronger performance, and since then it has become increasingly common for institutions allocating money to fund managers demand a high active share. As the chart shows, active share did indeed grow after the crisis, but has now been declining for several years. The success of crowded trades this year makes it easy to understand why:

The herd psychology isn’t just visible at the level of individual stocks. If we look at funds’ sectoral holdings, the same pattern appears. The sectors in which funds were overweight at the beginning of the year are now even more overweight, and vice versa. There has been very little rotating from successful sectors, or profit-taking thus far:

This is good evidence that a correction was needed, and that it might have further to go. For the longer term, the issue of how fund managers are paid and incentivized looks to be a critical one if markets are to avoid a cycle of bubble and bust.

RBG

This year’s electoral “October Surprise” came in September, with the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg arriving by tragic coincidence just as the Jewish holiday of Rosh Hashanah began. Ginsburg was arguably the best-known member of the Supreme Court in generations, and a figure who came to take on immense cultural significance. There have been some superb appreciations of her life in the last 48 hours, and you can find them here.

For now, the crude but necessary question is: How exactly is her passing likely to affect markets? We should split the question into two. First, does it change the odds on the likely winner of the presidency, or the Senate? Second, does it increase the chance of the “nightmare scenario,” of significant civil disorder or a constitutional crisis?

My guess is that the answer to the first question is “no.” Normally, conservative voters are more invigorated by a court vacancy than liberals are. But RBG’s sainted status among many on the left could change that. S&P 500 futures opened in Asia with little change, while betting and prediction markets have shown minimal shifts since the news broke.

The answer to the second question, however, has to be “yes.” The Supreme Court rules on issues that matter passionately to many Americans, such as abortion and gun rights. A fight for a seat that could change the court’s balance will raise the temperature. Add to this the deep ill feeling created by the process, and there is every chance of mass demonstrations and civil disobedience before the election.

Beyond the chance of disorder, the risk of a constitutional crisis is deepening. Democrats are incensed that Republicans refused to let Barack Obama’s nominee Merrick Garland have a vote in similar circumstances four years ago, but seem intent on pressing ahead now. Much will depend on whether they can successfully label the Republicans as hypocrites.

The problem is that having done this, the Democrats will have reduced the perceived legitimacy of the court. And their only weapons for stopping a new justice being appointed before the next presidential term starts are extreme. Should they win the presidency and Senate, they can plausibly threaten to expand the court. This would recreate a liberal majority and do grave damage to the court as an institution. Democrats can also threaten to deal with the inherent pro-Republican bias in the Senate and the electoral college by pressing ahead with attempts to make Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia into states.

Threatening this as brinkmanship might persuade Republicans not to push ahead with filling the vacancy. But beyond the scenario of a contested election, this raises the possibility of renewed constitutional upheavals once a President Biden were to take office. These risks aren’t negligible. It is prudent for investors to take them into account.

Survival Tips:

How exactly did the waif-like Ruth Bader Ginsburg survive numerous bouts of cancer to live as long as she did? Depending on how you look at it, her decision not to resign six years ago, while Democrats still held the White House and Senate, showed either misguided arrogance, or a thrilling and cussed determination to live on. Her work-out regimes are legendary. And of course she is nicknamed after a rapper who didn’t live to see anything like such an advanced age.

One other key to her longevity is her well-known love of opera. She even played a cameo in a Donizetti work four years ago, while her unlikely friendship with conservative Justice Antonin Scalia even became the subject of its own comic opera, Scalia/Ginsburg. Usefully, the New Yorker ran a list of her favorite operas eight years ago. Those with a Pandora account can listen to an interview with RBG here.

There are few better ways to escape the stresses caused by the effort to replace Scalia and Ginsburg than to dig through some of the operas she recommended here. To get started, I’d suggest The Rake’s Progress by Stravinsky, one of her more avant-garde suggestions, or La Ci Darem La Mano from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, a gloriously seductive duet, with the great Bryn Terfel in the title role. Rest in peace, RBG, while your country tears itself apart over how to replace you.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets at Bloomberg. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.