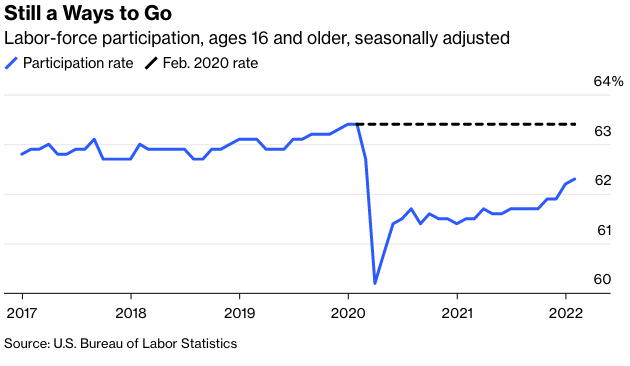

Despite spectacular job growth over the past 22 months, the U.S. labor-force participation rate is still 1.1 percentage points—which amounts to about 1.8 million people—short of where it was on the eve of the pandemic in February 2020.

The labor-force participation rate is the number of Americans 16 and older who either have jobs or are actively looking for them, divided by the population 16 and older. (Uniformed military personnel and those confined in prisons and other institutions are excluded from both sides of the equation.) The fact that participation is still so much lower, even as the unemployment rate moves close to pre-pandemic levels—it was 3.8% in February, versus 3.5% in early 2020—is both an explanation for some of the strange things going on in the labor market these days and a phenomenon that itself calls out for explanation.

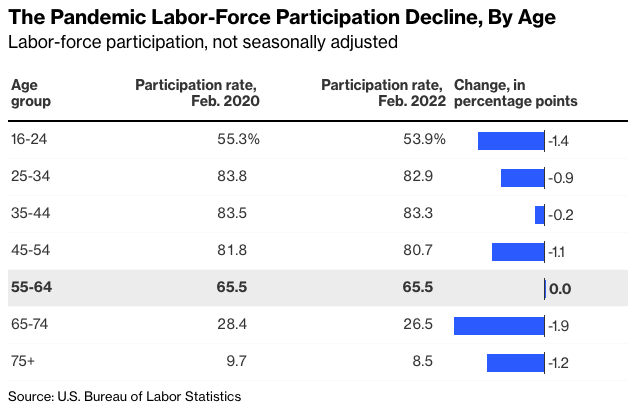

Part of what’s going on is just that Americans are getting old, with the eldest members of the giant baby boom cohort turning 76 this year. By the estimate of economists Jason Furman and Wilson Powell III, 0.3 percentage point of the decline in labor force participation since February 2020 can be chalked up to the aging of the population since then.

That still leaves a 0.8-percentage-point gap, though, and there are some interesting shifts within age groups that may help explain it. Because the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t adjust all of its age-group numbers for seasonal factors, comparisons that mix months can be misleading, so the February jobs numbers released last week provide a good occasion to look back at what’s changed since just before the pandemic in February 2020.

The general pattern is smaller losses among those in their prime career years and larger ones for those nearer the beginning and the end. The 45-to-54-year-olds are a big exception, and I’ll admit straight away that I don’t know what’s going on there. The group’s labor-force-participation decline has been concentrated among those 45 through 49, has affected men and women similarly and does not seem to be connected to population adjustments that the Bureau of Labor Statistics made in January to incorporate the results of the 2020 U.S. Census (that is, there was no big drop from December to January). Maybe it’s a fluke, maybe it’s not.

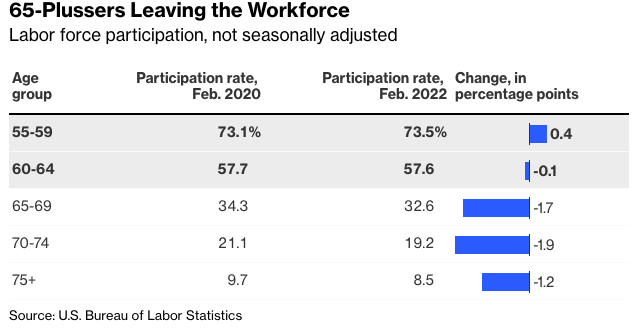

The participation declines among those 65 and older aren’t a fluke, and a lot has been written about them already. A pandemic that was most dangerous for the elderly, coupled with an asset-price boom that was kind to those with retirement savings and home equity, led a lot of Americans 65 and older who were still working to retire.

Some of these people will unretire if the Covid-19 threat continues to recede and the job market continues to boom, but the hit to labor-force participation among those 65 through 74 has been so big that it’s hard to see the gap being closed quickly. Those in their late 50s and early 60s have been the least likely to drop out of the labor force of any age group, so the best hope may simply be to wait until they (or should I say we, since that’s my cohort) move into their late 60s and early 70s.

Which leaves the young folks.

The big increase in labor-force participation among 16-and-17-year-olds comes after decades of declines, and fits well with anecdotal evidence of desperate employers taking chances on unexperienced teenagers and those teens being (rationally) less worried than adults about catching Covid on the job. The sharp decline among 18- and 19-year-olds is weird, and doesn’t really fit with other evidence such as enrollment declines at two-year colleges. The BLS does seasonally adjust the participation rates for both those groups, as well as for 20-to-24-year-olds, so it’s possible to view their trajectories over the course of the pandemic. The 18-19 line has certainly jumped around a lot, so I wouldn’t read too much into the recent decline.

Labor-force participation among those 20 through 24 has followed a steadier line. It’s been rising, but is still well short of the pre-pandemic rate. Explaining this, and the smaller but still significant participation declines among those in their late 20s and early 30s, has become something of a cottage industry over the past year.

Much of the talk has centered around a supposed attitude shift toward work described variously as the “Great Resignation” or “Lying Flat,” but hard evidence for this has been mostly wanting. (Goldman Sachs economist Joseph Briggs simply offered up a chart showing rising activity on the r/Antiwork subreddit, for example.) And while there is ample evidence that struggles with child-care during the pandemic have kept lots of women out of the labor force, women in their early 20s are a lot less likely to have kids than they used to be.

My own based-on-little-evidence theory is that the pandemic, and especially the total shutdown of spring and summer 2020, was so disruptive for young people finishing their educations and entering the job market that it’s taking a long time for them to catch up. Figuring out one’s initial path into a career isn’t easy in normal times, and having that path completely blocked for many months has got to have an impact.

I tried this explanation out on a couple of economists at companies in the job-search space, and met with some agreement. “It was a forced gap year, essentially,” said Nick Bunker, director of economic research at the Indeed Hiring Lab. “Things were so uncertain. There was mass unemployment in jobs that didn’t require a college degree.” Daniel Zhao, senior economist at Glassdoor Economic Research, pointed to sharply rising median wages for 16-to-24-year olds (10.6% over the 12 months ending in January, according to the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker) as an indication both of shortages of younger workers and, more positively, “some scarring effects from the Covid recession being avoided for new young workers in the labor force.”

Graduating in the midst of past recessions has brought negative effects on earnings that persist for as much as a decade. The rebound from the Covid-19 recession has been so rapid that perhaps that long-term scarring can be avoided—but it’s still a risk for hundreds of thousands of young Americans who have yet to find a way into the labor market.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of The Myth of the Rational Market.