Federal Reserve policymakers believe that inflation expectations are self-fulfilling prophecies, and they’re dead set on preventing them from moving materially higher. But expectations are hard to measure in real time, and the most popular household surveys are limited by respondents’ often poor understanding of what inflation truly is. They may confuse price levels with inflation (a rate of change), and they tend to over-extrapolate from a few narrow experiences at the gas station and the supermarket.

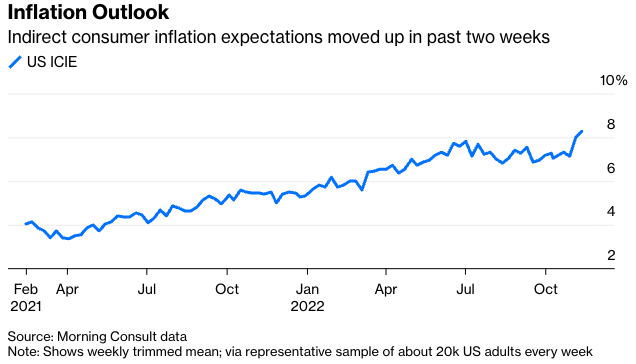

Of course, economists and survey architects are aware of these shortcomings, and there’s been considerable enthusiasm around the idea of making the questions more intuitive and personal. Morning Consult, in work with economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, introduced a survey question last year that asks consumers how their incomes would have to change to make them “equally well-off,” given their expectations about prices in the next 12 months. In the past couple of weeks, the Morning Consult metric—drawn from weekly surveys of 20,000 people on average—jumped to a record. I spoke to John Leer, chief economist at the decision intelligence company, about the recent data. A lightly condensed and edited transcript of the conversation follows.

What is your indirect consumer inflation expectations gauge telling us?

For the second week in a row, we’ve had really record high inflation expectations—up to 8.25% for the week ending this past Saturday, up from 8.02% the week prior. This in many ways sort of bucks the trend that we’ve seen over the last two months where we saw basically a lot of volatility that essentially resulted in instability. And now we’re clearly seeing a turning point with elevated inflation expectations… It’s hard to refute now—after having two consecutive weeks, 20,000 survey respondents per week—that 12-month inflation expectations are elevated.

What are the implications of that finding?

There’s a view now that folks actually will have to make more money, their wages would have to grow faster, to keep up with how they expect the price of goods and services to evolve. What we haven’t seen—and this is a separate paper—is I think folks don’t believe that they’re actually going to be made whole. They know that they would need to make in this instance 8.25% more to keep them at parity, but that would require a lot of negotiating power.

How do you solicit inflation expectations? Why do you think it’s a better way?

We ask people how much their wages would have to change to make them equally well-off for their expected changes in the price of goods and services that they buy. That’s valuable for a couple of reasons. First of all, the basket of goods: We cater to individuals. So we know that expectations tend to be better informed when you make it very micro-specific, very specific to the respondent…that’s benefit one. The other is framing it in terms of people’s wages. Inflation can be a hard concept for people to understand, even people who are fairly financially savvy. Is it prices? It’s not quite prices. Is it change in prices? Well it’s not quite a change in prices. It’s the rate of change in something called a price index. So what we’ve done here basically is by asking people about what they spend for their goods and services, in their head they’ve mentally constructed the basket of goods and services that they’re using. And then we’re asking folks about the rate of change in wages which again allows you to look at everything in a single number. And I think that’s functionally how people think about inflation: It’s going to make me poorer. OK, well how would I need to be offset to be equally well-off?

To what extent have politics pushed inflation expectations higher recently?

I would say that’s still my primary hypothesis [of what happened in the data in recent weeks]. We’re in early stages of testing that hypothesis, and really proving it or disproving it takes a little bit more work … but it’s been interesting because those inflation expectations remained high even after the election. I would have thought, OK, we’re going to have a divided government, spending’s probably going to be a little bit lower, there’ll be more gridlock…it is possible that it really is just fear-mongering, that we’ve got political ads hammering home high levels of inflation. That historical experience is what people use to inform their future expectations.

What’s certainly true right now is that 12 months ahead inflation expectations are elevated. The cause is only really, really valuable if you think that in the absence of those ad campaigns going forward that you would see a drop in inflation expectations, that this has just been an entirely temporary phenomenon. It might be; we’re two weeks into it. That’s the value of some of this high-frequency data, because we’re going to be able to track this stuff every week, and you’re more able to make some causal claims.

Your survey responses come from internet surveys. How do you respond to the survey purists who say internet surveys are inferior?

First and foremost, I think about the world in which we live currently, and you’ve got to be a realist about how people engage with surveys. Few people answer the door if somebody knocks. Even fewer people are going to answer their phone if an unexpected number rings, and so that’s just the reality in which we live… The second part is that in the U.S. internet penetration is extremely high across a shockingly high range of demographic groups, and that allows us to access a lot of different folks… The benefit there is that then gives us access to a very large sample at a very high frequency.

The issues with online surveys are very, very similar to the issues that folks have with non-response rates via phone surveys. You’ve got to address them one way or another in this current world, and my view is that we are able to provide a lot of value by doing the high-frequency large-scale surveys.

Short-term inflation expectations get short shrift. The Federal Reserve and many economists tend to focus on longer-term expectations when assessing whether expectations are well anchored. Your longer-term expectations data aren’t ready yet for public eyes, but in the meantime, why should we pay attention to the short-term expectations?

Our very preliminary take is that in our data it does not look like there’s a noticeable difference between 12-month and the five-year [inflation expectations]. The respondents do not seem to be as sensitive to the time horizon as what you see in some of these other surveys.

[Short-term] inflation expectations are certainly important for the wage-setting process, probably not in the U.S. as much as in Europe and places where they have a more unionized labor force and they go through a more formal wage-setting process. They’re coming up with their forecasts for inflation essentially, which they use to inform their wage bargaining. In the U.S., we essentially have rolling periods of wage negotiation since there’s fairly low union coverage. And I think that again doubles down on the need to have higher-frequency data, and I think the 12-month time horizon is appropriate.

Jonathan Levin has worked as a Bloomberg journalist in Latin America and the U.S., covering finance, markets and M&A. Most recently, he has served as the company's Miami bureau chief. He is a CFA charterholder.