Investors are facing important questions about their future in today’s investing climate. What is a safe withdrawal rate? What are reasonable return expectations for our portfolios? Let’s introduce a framework for these questions.

Over the last 50 years, U.S. equities have averaged annual returns of 10.56%. U.S. bonds averaged 7.43%. A U.S. portfolio of 70% equities and 30% bonds, rebalanced annually, would have averaged 10.03%. Importantly, if you add 70% of the return of the equities and 30% of the return of bonds, the result is not 10.03%. It is 9.62%. The 70/30 portfolio experienced a 0.41% bump with what is called “diversification return.”

In 1992 David Booth and Eugene Fama published “Diversification Returns and Asset Contributions,” in which they found, “The portfolio compound return is greater than the weighted average of the compound returns on the assets in the portfolio. The incremental return is due to diversification.”

This is the free lunch in investing. Diversification return occurs because of two factors. The first has to do with the math of a portfolio recovering from a loss—it needs to rise by a higher percentage than it lost to even out. A portfolio that declines 25% needs to rise 33% to break even. A portfolio that declines 50% needs to rise 100%. Decreasing a down period with non-correlated assets means future returns do not have to be so high.

The second factor is rebalancing, or the process of selling higher and buying lower over time. These two factors add diversification return in any sensible strategy over the long term. The more diversification you have in your portfolio, the higher your diversification return.

So how can one assess the reasonable expectations from their portfolio going forward? Valuation matters.

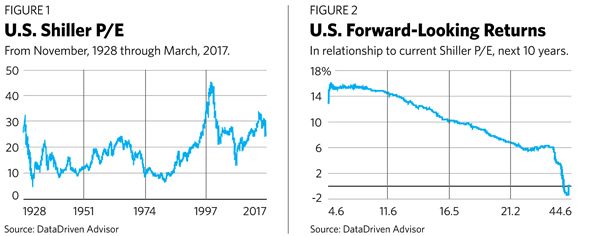

To understand this better, we need to look at the predictive power of the Shiller valuation (Figure 1).

Figure 1 shows the historical Shiller P/E for the S&P 500. High numbers imply an expensive market, low numbers a cheap market.

The chart on the right (Figure 2) displays the historical relationship between the current Shiller P/E and the average returns over the next 10 years. This data is over 90% correlated, and while some individual periods have varied from the forecast, this is generally an excellent indication of future returns. Since the forecast is medium to long term, some people get hung up on the timing. But this is as good an indicator of rational expectations as we have, and everyone is planning for the medium to long term, so our forecasts should align with the time line. Notice how when the Shiller P/E is low, high returns generally follow. Of course, it follows that when the Shiller P/E is high, low returns tend to follow.

How can we use this data? Since the Shiller P/E was 29 at the end of the second quarter of 2020, let’s transport ourselves back to the last time it was around that level at the end of the year—in December 2006. At that time, the 10-year U.S. bond yielded 4.71%. It would have been reasonable for investors to expect around 4.71% from their bonds. And their stocks? The Shiller P/E of 27 was one and a half standard deviations above median, implying that there would be 6.07% average annual returns going forward.

We could have said, “I expect 6.07% from my stock portfolio and 4.71% from my bond portfolio.” In that case, the math on expectations of a 70/30 portfolio would have been: 0.70% x 6.07% + 0.30% x 4.71% = 5.66%. Note that the diversification return is generally smaller for shorter time periods, so we would add in 0.32% to account for that (0.32% was the median diversification return for a 70/30 portfolio over 10-year periods as of December 31, 2006). So we add that in and get 5.98% expected average annual returns. Over the next decade, the returns of a 70/30 portfolio were actually 7.11%—pretty close to expectations and certainly far less than the long-term returns of the 70/30 portfolio (which had been 10.67% at that time!) Anyone expecting to obtain the average long-term returns would have been badly disappointed.

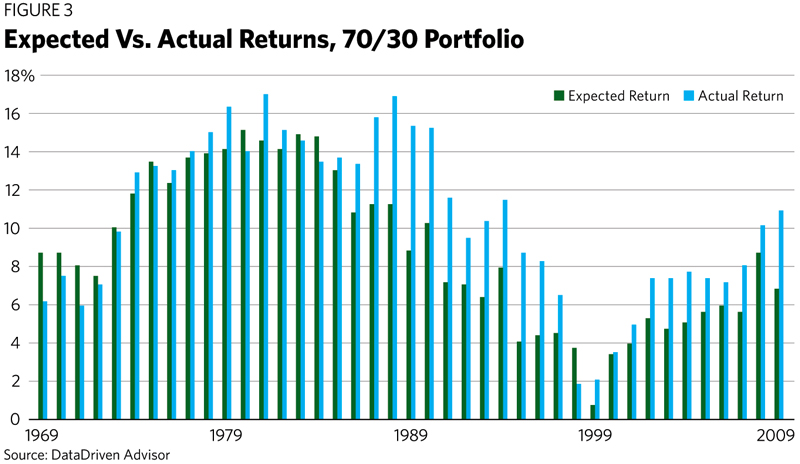

The next chart (Figure 3) shows us the complete historical data set comparing expectations with actual returns since 1970. The expected returns have been between 1% and 15%, while actual returns have fallen between 2% and 17%. Over a decade, returns face an uncomfortably wide range of outcomes, and that range depends almost entirely on the starting valuation. Note that 76% of the time, expected returns fell within 3% of actual returns. When the results did deviate by more than 3%, it coincided with periods of outperformance—during the internet bubble, for instance, or the period ending 2019 (the longest bull market on record). The data is over 85% correlated.

Where We Are Today

As of July 6, 2020, the 10-year U.S. government bond was yielding 0.68%. The Shiller P/E of 29.5 is over 1.5 standard deviations above median. This implies that the average annual returns for U.S. equities will be 4.32% going forward. So today, the math on expectations of a 70/30 portfolio should be 0.70% x 4.32% + 0.30% x 0.68% … or 3.23%.

Add in 0.35% for diversification return (the long-term average, as of early July), and the expectations should be 3.58% for a U.S. 70/30 portfolio going forward. Using the same methodology, the Shiller P/E forecast for average annual returns over the next seven years is an even more disappointing 2.35%. Said differently, over the next seven years, U.S. investors, regardless of their split between domestic stocks and bonds, should be expecting around 2% average annual returns.

Returns of 3.58% are likely not enough for most investors, especially considering that after deducting inflation, the real return is even lower.

So what can we do? Diversify.

Over the last 50 years, a diversified portfolio averaged 9.59%. But the added diversification return averaged 1.12% annually! This is a huge bump in today’s environment of low expectations. Recall, the more diversification you have, the higher your average diversification return.

We’ve already set our expectations for U.S. stocks and bonds at 4.32% and 0.68%. Let’s look at the other pieces of the diversified portfolio.

Let’s start with international bonds. A large international bond fund, the SPDR Bloomberg Barclays International Treasury Bond ETF (BWX), has a 30-day SEC yield of 0.47%. A large emerging market bond fund, the VanEck Vectors J.P. Morgan EM Local Currency Bond ETF (EMLC), has a 30-day SEC yield of 4.45%. For international bonds in total we’ll make a rough assumption of 70% in developed and 30% in emerging markets. So we should expect a return of 0.70% x 0.47% + 0.30% x 4.45%, or 1.66%, on our international bonds.

While this is similar to our U.S. bond expectations, there is a diversification element provided by holding international currencies. If the U.S. dollar depreciates, these bonds might do well. Of course, the reverse holds true if the dollar strengthens.

How about international stocks? Look at valuations for the four largest developed countries: Japan, Germany, the U.K. and France. For a visual, here is the Shiller P/E of Germany, the largest of the European countries (Figure 4).

How about international stocks? Look at valuations for the four largest developed countries: Japan, Germany, the U.K. and France. For a visual, here is the Shiller P/E of Germany, the largest of the European countries (Figure 4).

All of the largest developed international countries have valuations within a one-half standard deviation of their median (and all of them are below median), implying there will be a normal range of returns going forward. Over the last 50 years, developed international equities have averaged 9.33% annually, and with normal valuations this is our current expectation.

How about emerging markets? Here we will examine the valuations of the four largest emerging market countries—Brazil, Russia, India and China (the BRICs). Each has a valuation within a one-half deviation of its median (with three of the four countries seeing it fall below median). That implies there will be a normal range of returns going forward. Over the last 50 years, emerging market equities have averaged 12.02% annually. More conservatively, we’ll use the same 9.33% returns that developed international equities earned to set our expectations.

For international stocks in total, we’ll make a rough assumption of 70% in developed and 30% in emerging markets. In that case, we should expect a return of 9.33% (or 0.70% x 9.33% + 0.30% x 9.33%).

Now we get to the difficult stuff: real estate, gold and commodities.

Real estate is a bit troubling. We haven’t found any literature pointing to a framework to determine expected returns here (and if you know of any, please share). Looking at historical data, real estate investment trusts have averaged 8.90% over the last 50 years, and 8.18% since 2000. Taking a global approach and employing a reasonable amount of conservatism, let’s assume there is a return figure midway between our expectations for U.S. stocks (3.55%) and international stocks (9.33%). Thus, 6.44% seems like a reasonable expectation from REITs.

Gold and commodities are the most difficult to set expectations for, since they have no intrinsic value, earnings or dividends. Looking at the historical data, gold has averaged returns of 7.83% over the last 50 years, and 8.64% since 2000. Let’s take the lower of the two, 7.83%, for gold. Similarly, commodities have averaged 6.73% over the last 50 years, but have fallen 0.33% since 2000. To be conservative, let’s average the two periods and end with 3.20% as our outlook for commodities.

I define the diversified portfolio as equally weighting each asset class—U.S. stocks, U.S. bonds, international stocks, international bonds, real estate, gold and commodities. This is not how I recommend allocating a portfolio, but it is a reasonable way to discuss the features of diversification in general.

The expectation for a diversified portfolio would be one-seventh of each of the individual pieces:

(1/7)*4.32% + (1/7)*0.68% + (1/7)*1.66% + (1/7)*9.33% + (1/7)*6.44% + (1/7)*7.83% + (1/7)*3.20% = 4.78%.

As we did with the 70/30 portfolio, we add in the average diversification return: The median for a diversified portfolio over 10-year periods is 1.12% annually.

Taken together, our expectations for a diversified portfolio are 5.90%. This is almost 65% more than the expectation from a 70/30 portfolio alone. But don’t take my word for it. Plug in your own assumptions and position sizes.

We’ve rarely been faced with such low expectations on both U.S. equities and U.S. bonds at the same time. Today’s domestic investing market suggests that this is possibly the most important time in history for investors to be eschewing home bias and embracing a multi-asset-class, globally diversified portfolio. Let us be clear: The odds seem heavily stacked in the favor of diversification.

Randy Kurtz, CFP, is founder of the DataDriven Advisor, a registered investment advisory firm in Chicago. For more information, visit atadrivenadvisor.com.