For Stephen Yacktman, chief investment officer and portfolio manager at Yacktman Asset Management, the decision about which stocks to invest in, or whether to invest in stocks at all, rests largely on price. If he likes a company and its stock fits his valuation and quality parameters, it may be a good candidate for purchase. But if stock prices are exceeding his comfort zone, he is fine with sitting things out.

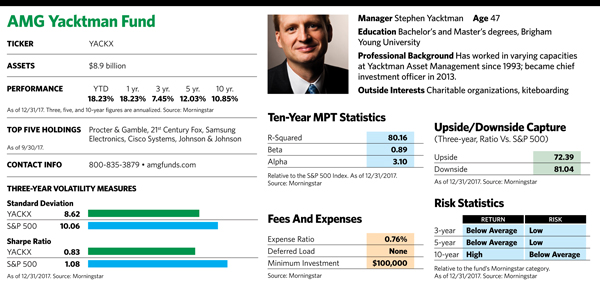

The latter conviction is the main reason that the AMG Yacktman Fund, the firm’s flagship offering, had nearly one-quarter of its assets in cash at the end of 2017. Since the end of 2011, the Standard & Poor’s 500 has more than doubled, while earnings have increased at a fraction of that pace. Using price-earnings multiples as a yardstick, the index is trading at one of its highest levels in history.

“We would not find it prudent to lower our standards to stretch for returns,” he told shareholders in a report issued late last year. “We believe there is far too little focus on risk today, and many will eventually be disappointed by the results that markets will achieve over the next decade.”

Yet despite the frothy market, there have been times the fund has seen buying opportunities. That happened in the late 1990s, when prices of tech stocks climbed to dizzying levels while value stocks remained relatively cheap and out of favor. Because the fund loaded up on those value stocks and remained fully invested, it was able to produce strong double-digit annualized returns between 2000 and 2009, while the S&P 500 sank.

But there are other times, such as 2007-2008 and today, when the rising market tide has lifted almost all stock boats. When that happens, the fund raises cash levels because quality bargains are much more difficult to find.

Yacktman’s willingness to sit things out is an anomaly in the world of mutual funds, which almost always have a mandate to stay fully invested in their respective asset classes. And while he acknowledges that having a cash hoard can be a drag on returns in expensive markets that keep going up, he believes it makes sense over the long term.

“Sure, expensive markets can get more expensive,” he says. “But our goal is to invest over a full market cycle, not for the next couple of months or years. And it’s better to keep money in cash than to lose money.” When managers are fully invested, he adds, they may be forced to sell stocks to meet redemptions amid the descending price cascade of a down market.

Maintaining high cash levels also means that when stocks become cheap again, his fund can be an aggressive and active bargain buyer.

Several charts on the firm’s website underscore its ability to beat the pack in difficult times. In the two years following the market peak in March 2000, for example, the AMG Yacktman Fund delivered an annualized return of 25.47%, while the S&P 500 fell 12.52%. Following the market peak in October 2007, the fund’s two-year annualized return was 4.05%, while the index fell 15.17%. Its resilience in down markets is one reason the fund has been a top performer in Morningstar’s large blend category over the last 10- and 15-year periods.

But the last few years have been more challenging ones for the fund. “This fund’s recent results continue to suffer as managers Stephen Yacktman and Jason Subotky refuse to chase stocks in what they consider to be an expensive market,” wrote Morningstar analyst Kevin McDevitt in a report issued late last year. “Such discipline has served the fund well over the long term, but it has meant missing out on a big chunk of the market’s gains following the mid-2011 correction.” Nonetheless, Morningstar assigns the fund four stars and a “Gold” rating for its patient and disciplined investment approach.

Not all shareholders, though, have been willing to wait things out. In 2014, the fund had $13.5 billion in assets, up from $300 million just five years earlier. Yet as of late last year, its asset base stood at only around $9 billion. A similar story unfolded for the AMG Yacktman Focused Fund, which has $4.5 billion in assets, down from $11.6 billion at the beginning of 2014.

Yacktman says many of those who left were performance chasers who didn’t really understand what the fund was about. Co-manager Jason Subotky stresses that it’s important for investors in this fund to understand its unique ebbs and flows and to hang in for a full market cycle to truly appreciate its value.

“We’re not trying to get the highest returns in expensive markets,” Subotky says. “Our shareholder base expects us to manage risk and perform well during difficult periods.”

Looking for Consistency

Like its allocation parameters, Yacktman’s stock picking approach is also fluid. While the goal is to buy high-quality companies at low prices, the fund’s holdings often straddle the growth-at-a-reasonable-price and value camps. Depending on pricing and other factors, its purchases may lean toward one end of that spectrum or the other.

Over the last few years, the emphasis on value and pricing has risen as high-quality growth stocks have gotten more expensive. Even among these bargains, the managers like to see a company enjoy high market share, high cash return on assets, relatively low capital requirements, reasonable debt, and unique franchises. The fund also likes a company’s management to be friendly to shareholders—to reinvest in its business, make synergistic acquisitions and pursue stock buybacks.

When Yacktman doesn’t find stocks he likes, he may sometimes invest in high-yield bonds. He made one such investment in the debt of beauty products company Avon. While Avon’s stock fared poorly in 2017 because of disappointing earnings, the company’s bonds were selling at a hefty discount. Yacktman bought them, and they offer attractive interest payments that Avon is well prepared to sustain over the long term.

The fund’s adaptable, wait-it-out approach reflects Yacktman’s long tenure at the firm, which his father, Donald Yacktman, founded in 1992 after spending 10 years managing Selected American Shares. Stephen, one of Donald’s seven children, joined the firm in April 1993 as an analyst soon after graduating from Brigham Young University. He served as co-manager for the AMG Yacktman Fund and AMG Yacktman Focused Fund beginning in 2002, and in 2006 he was named co-chief investment officer and senior vice president of the firm. In early 2013, he took over as chief investment officer. His father, now in his mid-70s, continues to work at the firm and contribute ideas.

While the fund’s strategy has remained fairly consistent over the years, Stephen, now 47, has initiated some changes. The firm used to assign analysts to specific industries, but found that doing so led to an industry bias. Now, analysts take a more generalist approach. The fund also owns more technology stocks than it did years ago, when the sector consisted of more volatile stocks and companies with erratic cash flows. And it has de-emphasized stocks of large banks, whose financial reports may not always reveal the full extent of the risks they are taking.

One thing that has not changed much over the years is that a large chunk of assets is dedicated to consumer staples companies, which the managers like because the cash flows of these companies are steadier and more predictable than those of other industries. “It’s often an underpriced and unexciting area of the market and a good place to be when everything else is so expensive,” says Yacktman. His holdings in this group include Procter & Gamble and PepsiCo. With its strong Frito-Lay business, the latter company, he believes, “probably has the best positioning of any large packaged food company in the world.”

The fund has added a few international stocks in the last couple of years because the managers believe these offer a better value than comparable stocks in the U.S. One top fund holding is Samsung, which trades on the South Korean exchange. It’s “cheap compared to Oracle or Microsoft,” says Yacktman. While the stock has appreciated substantially over the last year, the company’s earnings have increased substantially as well. Shares also remain relatively inexpensive, especially in light of Samsung’s substantial excess cash.

One of the benefits enjoyed by the undervalued and underappreciated companies his team looks for is that sometimes they become acquisition targets. That happened in mid-December 2017, when the Walt Disney Company announced a deal to buy most of the assets of longtime Yacktman fund holding 21st Century Fox for $52 billion in stock. Investors have worried about the future of traditional media companies, which are battling the likes of Netflix and Hulu, but Yacktman and Subotky believed investors were overlooking Fox’s valuable international assets such as Star, the leading media company in India, and its 39% ownership of Sky.

These are not part of high-cost U.S. television bundles and do not get hurt when U.S. consumers cancel their cable subscriptions. “Post close, Disney will be the best positioned traditional media company with a significantly improved global position,” says Yacktman. “The remaining Fox assets include Fox News, Fox Sports and its network and television station businesses. These assets could generate more than $2 billion in annual free cash flow.”