Carl reflects on the anniversary of the pandemic:

There are 73 sets of hash marks on the paper my wife uses to record the duration of her home confinement, five days at a time. The tally was kind of a joke at first, but it is now a sobering reminder that it’s been a year since lives and economies were turned upside down.

In early March of 2020, I visited several clients in Europe. It was a typically busy itinerary: seven cities in two weeks across five countries. The coronavirus had been in the news for several weeks already, but didn’t seem overly threatening. I found room for hand sanitizer in my luggage but didn’t expect to use it much.

When I arrived in Dublin to begin the journey, I learned the first Irish cases had been diagnosed and schools were to be closed. An outbreak in northern Italy had been spread to other European cities by skiers who had gone to Lombardy for a spring holiday. Clients began cancelling our meetings, and we ultimately decided to cut the trip short. I flew home a week early and spent a couple of days in the office upon my return. I haven’t been to the airport or the office since then.

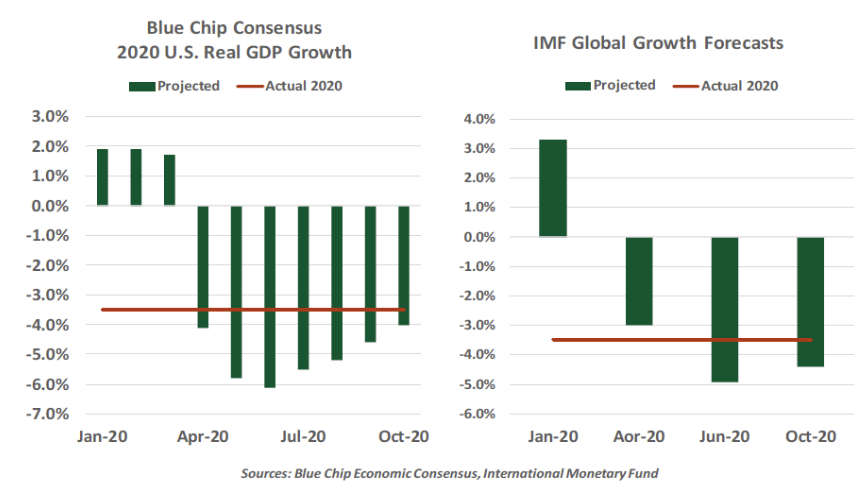

At the outset, many of us presumed we were facing a relatively temporary interruption. (For a time, I continued paying for a monthly train pass and a gym membership close to the office.) Early analysis of the situation determined it would manifest largely as a supply shock affecting production chains that snaked through China. Our forecasts, and those produced by others, were slow to recognize the extent of the damage that would ultimately be done to commerce.

As reality set in, markets found themselves behind the curve and facing an excess of unknowns. Trading became extremely volatile, and liquidity was drained from financial markets. In response, the U.S. Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near zero in two huge chunks, and opened a series of support programs for troubled sectors. The market frenzy of March 2020 eventually calmed, but the global economy had been deeply damaged.

No Country Has Done A Flawless Job Of Dealing With The Pandemic

Societies have had to make difficult choices over the past year as they’ve balanced public and economic health. Some have remained more open, finding restrictions untenable; others took more aggressive steps to limit contagion. In between are a large number of countries that have vacillated between the two. It hasn’t been easy to set a steady course: information used to guide policy has undergone update and revision; local circumstances and local politics have introduced complications. While leaders have been hailed and faulted for their management of the situation, no country has handled Covid-19 flawlessly.

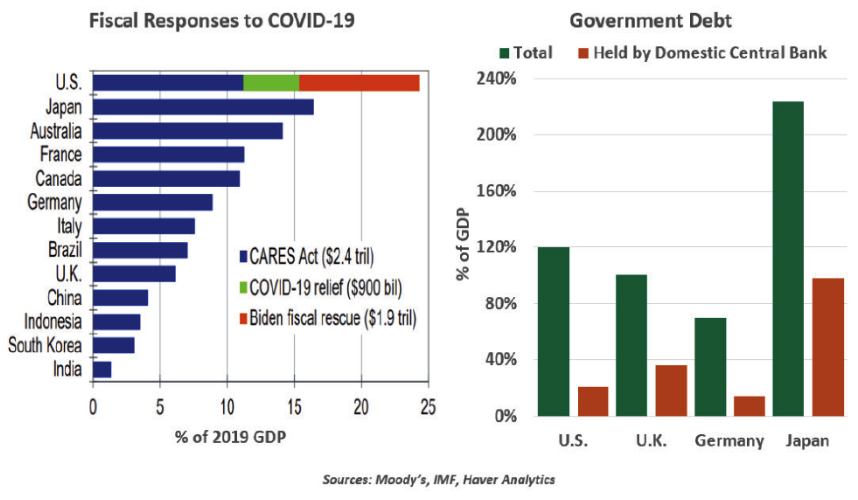

Richer countries have spent immense sums to cushion the impact of the pandemic. Balancing the speed of action and care in the design has not been easy. The U.S. has decided to go very big, Europe has lagged, and some emerging markets have barely gotten started. These differentials will be reflected in relative economic performance. Central banks have served as enablers, absorbing substantial volumes of government debt.

Many countries did not enter the pandemic in the best long-run fiscal shape. While addressing the proximate challenge required aid on a large scale, the issue of how much debt is too much debt will be debated even more actively in the years ahead. So will the proper scale of central bank balance sheets, which have grown by leaps and bounds.

Financial markets have certainly performed far better than expected over the past 12 months, taking flight on the wings of policy support and vaccination prospects. At times, it has been hard to reconcile the optimism of investors with the troubling news on economic activity. That kind of “K-shaped” recovery pattern has been seen at many levels, and will be with us for some time.

At the moment, things are looking up. While not fully contained, Covid-19 is being brought closer to heel in many countries, which should allow additional mobility and economic activity. There is substantial pent-up demand and saving around the world, which should create a second “V-shaped” leg for the recovery. Forecasts are currently being revised upward at almost the same rate they were being downgraded 12 months ago.

Beyond the next four quarters, the pandemic will almost certainly have lasting impacts, which will need to be managed carefully. Individuals and industries may struggle with after-effects for a long while after the pandemic dissipates.

Following all of this from the confines of my house has been a bit surreal. Like many, I have been working harder in the last year, analyzing the dramatic changes to the world caused by an organism only .07 microns in size.

The Outlook Is Improving, But Full Recovery Is Still A Long Way Off

I still see articles suggesting craft and home improvement projects to keep office refugees from getting bored, but most of the people I correspond with do not have a surfeit of extra time. I feel like I am living where I work, not working from home.

Nonetheless, I feel incredibly fortunate. Our family has maintained good health, and I have a job that can be done from home. Our son’s wedding had to be postponed and two graduations will be held virtually this spring, but these are small inconveniences compared to what others have endured. My heart and my thoughts go out to families that have been touched by Covid-19, and my admiration goes out to the caregivers who have tended to the sick.

My wife and I received our first vaccinations last week. We felt different when we returned home; not because our shoulders were sore, but because an end to our isolation was in sight. There is a lot of quality time with family and friends to catch up on; a lot of hugs and handshakes deferred, and celebrations put on hold. One day soon, we hope, the hash marks will stop.

Little Kids Get Big Benefit

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 was ratified last week. Much attention has been focused on the $1,400 economic impact payments and the extension of $300 supplementary unemployment benefits called for in the bill. But the Act went further than simple Covid relief, reshaping taxes in a way that will change children’s lives.

Poverty in the U.S. is defined as lacking a minimum income to afford food and necessities. That minimum is indexed to inflation and adjusted for household size. The poverty line for a single American parent with one child in 2020 is $17,839; for a household of two adults and two children, $26,246. As of 2019, 10.5% of the U.S. population lived in poverty, including more than 10 million children under age 18.

Parents may recognize the child tax credit. Through 2020, it was a helpful annual income tax credit of $2,000 per child. Households that did not earn enough to have accrued $2,000 in income tax liability could receive a partial $1,400 refund.

Starting in 2021, the child tax credit will increase to $3,000 per child, or $3,600 for children under age six. Instead of realizing the credit upon the filing of a tax return, starting in July, families will receive this tax credit as a monthly distribution of $250 or $300 directly to their bank accounts. Every parent with an income of under $75,000 (or couples filing jointly earning up to $150,000) will automatically receive payments. And crucially, even parents with low or no income will receive the full value. Higher earners (households under $400,000) will still qualify for the previous $2,000 annual credit.

Disbursing money monthly to parents is novel in the U.S., but other nations have successfully piloted similar programs. The majority of OECD nations offer modest, means-tested cash benefits to parents. Critics of the program have raised objections that payments create a disincentive to work, but studies of these other nations’ programs, such as a recent study of the Canada Child Benefit, found no reduction in labor force participation.

The new system of child tax credits will function like Social Security for parents.

The bill contains other provisions that fight poverty. Children and adult dependents are eligible for the full value of the one-time $1,400 economic impact payments. Health insurance subsidies were enlarged, expanded nutrition benefits were continued through the end of 2021, and lower-wage workers without children will receive a larger Earned Income Tax Credit.

Analyses by the Urban Institute and Columbia University each concluded that in total, the provisions of the Rescue Plan Act will increase incomes enough to halve the number of households below the poverty line. The Urban Institute found the new child tax credit alone would reduce the child poverty rate from 13.7% to 11.3%, lifting 1.7 million children out of poverty in one year. At a cost of $135 billion for the 2021 benefit (7% of the Rescue Plan’s cost), the investment will generate a considerable return. The combination of one-time payments, child tax incentives, expanded unemployment and nutrition assistance pack a powerful punch.

The premise of a bill reducing child poverty by half might make one wonder if there could be a policy that eliminates child poverty. Programs of such size would be a bridge too far for most legislators, and the cash infusion could spur excessive inflation. But targeted measures to help children and support family formation can find an ongoing role; programs like Social Security and Medicare once sounded generous, but are now part of the economic fabric.

The revised tax credit can be regarded as a pilot program scheduled to expire after one year. When advance payments start to arrive over the summer, parents may find themselves pleasantly surprised; if payments stop in 2022, legislators may face difficult questions.

A nation facing demographic challenges and needing to enhance its human capital should consider all remedies that can support child-raising. This experimental policy could prove to be the most beneficial legacy of the nation’s Covid response.

Free World?

During the past year, governments around the globe have invoked executive powers, restrictions on liberty and surveillance to deal with the pandemic. Every type of regime took some measures, from authoritarian states like Jordan to traditional democracies like the U.K. While extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures, there is a growing concern some governments will continue to rely on these powers even after the pandemic is over.

Looking at the broader trend of democracy around the world, those concerns are not entirely unwarranted. Democracy has been faltering in the past decade and a half, reflected in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index and Freedom House’s latest report. Hong Kong’s independence is under increased threat due to the new national security law, as is the region’s status as a leading financial center and trade hub. India, the world’s largest democracy, was recently downgraded to “partly free.”

Democracy Offers A Better Framework For Growth Than Autocratic Regimes

Recently, China’s rise as an economic powerhouse has contributed to a belief that a more authoritarian system is best for economic growth. China’s apparent success in managing the pandemic has only strengthened the sentiment. A number of countries are finding value in a more directed model that avoids the messiness of government by the people.

However, much evidence contradicts this notion. Studies show that democracy does cause growth. Countries that switch to democratic rule achieve about 20% higher gross domestic product per capita in the long run, as democracy promotes investments and education. Social conflict falls while economic development rises. Additional accountability reduces corruption and inefficiency.

In sum, research finds that democracy offers a better framework for economic development than do autocratic or authoritarian regimes. That said, democracies certainly have room for improvement in responding to crises, when the need for decisive action is at odds with a deliberative system.

Winston Churchill once observed that “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” Hopefully, the pandemic won’t cause populations to think otherwise.

Carl R. Tannenbaum is executive vice president and chief economist at Northern Trust. Ryan James Boyle is vice president and senior economist at Northern Trust. Vaibhav Tandon is second vice president and an economist Northern Trust.