One of the most popular and reliable touchstones of investment strategy is value. Buying stocks with lots of current good things—book value, earnings, dividends—per dollar spent does better in the long run than buying stocks with hoped-for future good things. This principle seems to apply to other assets as well.

But this is a long-term claim measured over large portfolios tracked over many decades. Value goes through extended periods of underperformance, often when markets are frothy and investors are pouring even more money into the most overvalued assets. The 2010s were not kind to value, especially from 2017 to 2020, but the 2020s are making up for the losses rapidly.

A popular explanation for the trends is that value is an interest rate bet. The story goes that value stocks deliver cash flows in the immediate future, while growth stocks promise cash flows farther in the future. (I use “growth” to indicate the opposite of value, which is common usage. But to be more precise, non-value stocks are expensive, with high market prices relative to book value or other fundamentals. The reason they are expensive is usually because investors expect above-average growth, but there are sometimes other reasons.) At high rates, the present value of future cash flows is diminished relative to current cash flows, so value stocks are attractive relative to growth. But when rates are low, value is less attractive. The underperformance of value occurred at a time of low rates, and value revived when rates started to climb.

Hedge fund manager Cliff Asness of AQR Capital Management LLC (who I spent a decade working for) recently demolished this popular explanation on both theoretical and empirical grounds. But he did agree that value has been trading this way for a while, and that likely means it will continue to trade this way for a while. So, what’s an investor to do?

If you think value requires increasing rates to do well, then it doesn’t seem like a good strategy at the moment. The Federal Reserve is raising short-term rates with the intention of fighting inflation. If it works, long-term rates should go down on reduced inflation expectations. If it doesn’t work, we could end up in a recession, with even lower long-term rates. In either case, the Fed will eventually cut rates. The only scenario for continually increasing long-term rates is a disastrous repeat of the 1970s, with the Fed doing just enough to slow the economy without reducing inflation. Even in that case, value could likely outperform growth as it did in the 1970s, but no stock portfolio is likely to do well.

Asness based his empirical case on the correlation between changes in the 10-year U.S. Treasury note’s yield and the performance of a portfolio long value stocks and short growth stocks. A positive correlation supports the idea that value requires rising rates. Asness shows that the correlation wanders up and down over time, seldom far from zero, and more often negative (falling rates help value) than positive. Only relatively recently have we seen a sustained significant positive correlation.

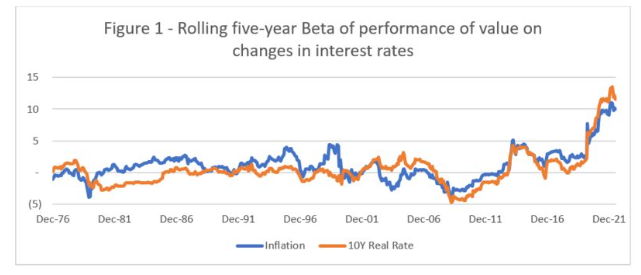

Figure 1 repeats the analysis with three changes. (These are my calculations based on data from AQR.) I decomposed the 10-year Treasury yield into an inflation component and a real rate (the nominal yield minus forecast inflation). Because inflation in gold-standard days was qualitatively different than fiat-money inflation, I only used data since 1971, while Asness goes back to 1926. Third, I show beta rather than correlation.

The two statistics are similar, but correlation is more useful to show how reliable an association is—statistical significance—which was Asness’s concern. Beta indicates the size of the effect—practical significance—which is what I want to discuss. The current betas around 10, for example, mean a 50-basis-point increase in either inflation or 10-year Treasury yields is associated with value outperforming growth by 5%, an amount that is certainly of investment interest.

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the 10-year Treasury real yield seemed to have little effect on the value factor. That further undercuts the popular story of why rates matter for value, since that story should depend on the real rate. There does seem to be a mostly positive correlation with value, ranging from a beta of zero to almost five. Perhaps value stocks are more able to recapture inflation than growth stocks.

But my chart, unlike Asness’s, seems to show a regime change with the 2008 financial market, rapidly increasing betas, and both inflation and real rate betas moving in lockstep. That suggests the performance of value depends on nominal rates rather than inflation or real rates. It’s hard to come up with economic arguments for that.

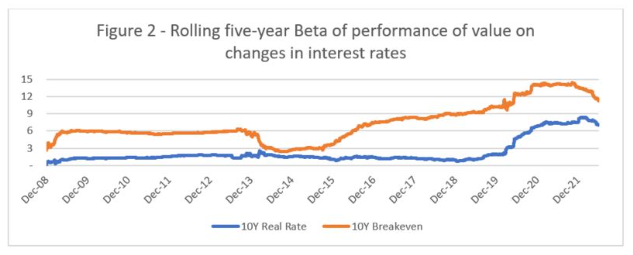

Figure 2 is a similar chart focusing on the period of interest (Same sources as Figure 1, plus the St. Louis Fed). For these years I can estimate expected future inflation using the 10-year Treasury breakeven rate and use daily rather than monthly data for more precision (The yield on 10-year treasuries minus the yield on 10-year TIPS.). In this version value seems to react more to inflation than to real rates, and to have a strong positive reaction to both. The inflation beta started increasing rapidly in 2015, and the real-rate beta in 2020. This appears to be to be a regime change from the pre-2008 pattern of zero real rate beta and inflation beta ranging from zero to five, up and down.

Where does that leave us? One answer is to ignore the recent correlations and look to both theory and long-term patterns. Based on long-term history, value should deliver 17% extra total return over the next five years.

Another answer is to use the most recent five years of data and ignore theory and earlier performance. That predicts value will deliver 22% extra performance over the next five years if rates don’t move. If rates, both inflation expectations and real rates, fall to zero, value would have a negative 9% performance. If rates doubled, value would deliver 53% extra.

To me that makes value seem like a pretty good bet. While zero or even negative rates are possible, I think it unlikely they will fall low enough to bring value to negative territory, even if the last five years are perfect predictors of the future. A doubling of rates, while also unlikely, strikes me as more plausible than a drop to zero, and both inflation expectations and real rates significantly higher than today seem likely.

It’s certainly worth Asness’s time to think about a possible regime change in the effect of rates on the value factor, but even if you throw out all theory and evidence before 2017, the correlations do not seem strong enough to render value unattractive. You would need to be sure that falling rates kill value, and also very sure that both inflation and real rates will fall to near zero, to abandon value now.

Aaron Brown is a former managing director and head of financial market research at AQR Capital Management. He is author of The Poker Face of Wall Street. He may have a stake in the areas he writes about.