Most financial advisors are familiar with the problem that projected healthcare costs will pose to people in retirement—numbers that are, to say the least, alarming.

Fidelity Investments noted this year that an average retired 65-year-old couple in 2022 may need a mind-boggling savings of $315,000 (after tax) to cover their retirement healthcare expenses. Earlier this year, the Employee Benefit Research Institute noted that a 65-year-old couple with median prescription drug expenses needed $296,000 in savings for a 90% chance of having enough to cover their healthcare expenses in retirement.

But most financial planners aren’t telling clients to have that much money set aside. Instead, some are taking to heart recent research published by T. Rowe Price and Vanguard/Mercer Health & Benefits.

View Costs As An Annual Expense, Not A Lump Sum

Specifically, they are looking at healthcare costs as an annual expense instead of as a lump sum. That makes such expenses easier for retirees to plan and pay for, according to Sudipto Banerjee, a vice president at T. Rowe Price, who wrote one of several reports on the topic.

Financial advisor Massi De Santis uses Fidelity’s lump-sum estimate as a starting point to guestimate what a client’s annual healthcare expenses will be. “The $300,000 for a couple seems scary, but it is about $6,000 per year, per person,” says De Santis, the founder of DESMO Wealth Advisors in Austin, Texas. “Think of $150,000 divided by 25 years equals $6,000. I usually express the number to the clients as an annual average figure, instead of the sticker shock of $300,000.”

A joint report by Vanguard and Mercer Health & Benefits echoes that point of view: “We believe a better planning framework considers [healthcare] costs as annual expenses personalized to an individual’s health status, coverage choices, retirement age and loss of any employer subsidies,” says the report, titled “Planning For Health Care Costs In Retirement.”

De Santis, however, doesn’t rely solely on averages when incorporating healthcare expenses as part of a client’s financial plan. “It’s important to realize that the $6,000 is an average number,” he says. “Some years, especially the early years, this number can be much lower, and some years much higher if there is an unexpected surgery, etc. Some people that are healthier may end up paying less. Some may end up paying more, but there will be a cap due to out-of-pocket maximums. For this reason, I suggest starting with the average, which is conservative at the start, and review/revise the plan over time.”

In fact, as his clients get closer to retirement or if the clients are retired, he refines the $6,000 per person number using their state and health status, as well as a tool for financial advisors provided by Vanguard. “So we get a more personalized estimate,” he says.

Financial advisor Patrick Kuster, with Buckingham Strategic Wealth, agrees with that approach and says advisors “should consider planning for anticipated, annual healthcare expenses as part of a client’s annual income needs, while still customizing plans for large, unexpected out-of-pocket expenses that may come up through retirement. … As client health, age, life expectancy, location, preference and means vary, so should the numbers in their financial plans,” Kuster says.

Premiums From Monthly Income, Out-Of-Pocket Expenses From Savings

So how might financial advisors go about helping their clients plan for these costs? First, by breaking the costs down into those that are fixed and those that vary. According to Banerjee’s research, health insurance premiums are usually fixed and can be budgeted for and funded from monthly income. Out-of-pocket expenses can vary from month to month, however, and his research shows they could be paid from savings or a fund earmarked for those purposes.

Consider: For people age 65 and over who have traditional Medicare (Parts A and B) and a prescription drug plan (Part D), annual premiums are $2,500 for the 25th percentile and $3,300 for the 90th percentile. In comparison, out-of-pocket expenses for the 25th percentile are only $300 and they’re $5,000 for the 90th.

Not all advisors break out fixed and variable costs, however. “I don’t think it’s useful to just plan for the premium as fixed liabilities and the deductible and coinsurance as discretionary expenses, because they are not,” De Santis says. “What I think is useful with a client is to review how much will be fixed [the premiums] and how much may be variable [coinsurance and deductibles].

That usually gives clients peace of mind, he says, “because it clarifies the meaning of the $6,000 per year we use as an initial estimate.”

Of course, financial advisors also want to plan for their clients’ all-in cost of healthcare. At one end of the spectrum, those one in four retirees in the 25th percentile who are covered by traditional Medicare (Parts A and B) and a prescription drug plan (Part D), including out-of-pocket expenses, will pay less than $2,700 per year for annual healthcare expenses, according to Banerjee’s research. At the other end of the spectrum, one in 10 retirees—those in the 90th percentile—will spend more than $7,800 annually on total healthcare costs, the median expense being $3,500.

The Mercer-Vanguard research has different estimates, but the results are similar. It shows that a low-risk, 65-year-old woman under original Medicare, in 2020, would have median costs of $3,100 pear year, a medium-risk woman would have median costs of $4,000, and a high-risk woman would have median costs of $6,700.

Wealth advisor Jason Branning advises clients to further reduce the variability of their out-of-pocket expenses by purchasing a Medicare Supplement Insurance plan, or Medigap, typically Plan F (for those who still qualify) or Plan G.

Medigap plans cost on average $150 to $200 per month according to Kaiser Family Foundation. They can help clients cover copayments, coinsurance and deductibles copayments, says Branning, who is with Branning Wealth Management in Ridgeland, Miss.

“These Medigap plans cover a majority of the medical costs annually for retirees through their monthly premiums,” Branning says. “Our advice is to cover these mandatory costs—health insurance—by matching them to stable income.”

That stable income includes Social Security, pensions (if the clients are lucky enough to have one) and earned income (if they are still working). Branning also uses withdrawals from various taxable and retirement accounts, such as IRAs and health savings accounts (HSAs) when necessary, as well.

The Mercer-Vanguard model suggests that a typical 65-year-old woman who purchased a Medicare Supplement Plan G and a standard prescription drug plan would have annual healthcare expenses of $5,100 in 2020.

“For those who can afford it, purchasing a Medigap plan that covers most of what Medicare doesn’t pay can lead to a highly predictable healthcare budget and heavily limit out-of-pocket medical expenditures,” says Kuster. “But doing so comes at an expense. Compared to lower cost Medigap policies with potential higher out-of-pocket expenses, buying a more expensive plan also means experiencing higher premiums, even if you don’t use the plan often. It’s wise to weigh the benefits and disadvantages of other insurance options, such as a Medicare Advantage plan or any retiree medical benefits available.”

De Santis says the question about Medigap is specific to each individual. “But Medigap is a good option if someone thinks they may see a doctor frequently and are concerned about the deductibles and copays,” he says. “I think it’s a good option to evaluate with the specific client.”

To be sure, retirement healthcare costs can vary widely depending on the type of insurance a retiree chooses, and no type of coverage is “typical,” according to Banerjee.

The authors of the Mercer-Vanguard research share that opinion: “Coverages differ in cost and comprehensiveness, and retirees need to make trade-off decisions when selecting a plan,” they write. “Total costs under different Medicare coverages may vary based on health status. Some people may consider paying higher premiums to reduce the risk of extreme or less predictable out-of-pocket costs. Others, especially those who expect to remain healthy, may experience lower costs in most years by opting for a less-extensive supplemental policy or none at all. The trade-off is that they may experience years with much higher costs. Waiting until supplemental coverage is needed may not be advisable, as many carriers will not provide that option after an individual becomes sick—outside of the initial Medicare enrollment period—or will charge higher rates.”

Planning For Prescription Costs

The just-passed Inflation Reduction Act will also change how financial advisors plan their clients’ healthcare costs in retirement. The law caps out-of-pocket prescription drug costs at $2,000 annually per Medicare beneficiary starting in

2025. Original Medicare, combined with a strong Medigap and efficient Part D coverage, means less risk of unexpected out-of-pocket healthcare costs through retirement, says Kuster.

Wild Cards To Be Considered

There are some other wild cards to plan for as well, including income-related monthly adjustment amounts (or IRMAA) on Part B and Part D premiums. “All Medicare enrollees start off by paying a standard amount, while higher income earners pay more for the same coverage,” says Kuster.

The calculation, he notes, is based on adjusted gross income plus certain foreign-earned income and tax-exempt interest (also known as modified adjusted gross income, or MAGI) from two years prior. For example, an individual’s 2024 Medicare costs are based on 2022’s MAGI.

Advisors must also consider how inflation will affect people’s healthcare costs.

For instance, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services projects an average annual Medicare spending increase of 6.7% between 2023 and 2030. And Fidelity’s Retiree Health Care Cost Estimate tool currently predicts a 4.9% healthcare inflation rate in retirement. “When planning for longer periods of time, it’s anticipated that a more conservative inflation number can be used in the assumption,” Kuster says.

What’s more, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services project an average annual Medicare spending per beneficiary increase of 4.5% between 2023 and 2030, and it is assumed that Medigap plans may experience similar increases over this time.

When thinking about the long-term projections of Medigap premium costs, Kuster says it’s important to note that supplements essentially pay the portions of Medicare-approved medical claims that weren’t covered by Medicare Part A or B. “The coverage is based on the prices Medicare negotiates and reflects a very similar utilization that Medicare experiences,” he says. “Therefore, we should expect Medigap premiums to increase within a reasonable range of Medicare’s increasing costs per beneficiary.”

Advisors must also account for the fact that Medicare and Medigap do not provide any dental coverages; though many Medicare Advantage plans have added some dental coverage, those plans typically have caps on how much they pay. “This leaves those with large dental procedures still needing to plan for sizable out-of-pocket costs,” Kuster says.

Planning For Long-Term Costs

The biggest wild card when it comes to healthcare expenses—expensive healthcare shocks and long-term care—can also be planned for.

According to Banerjee’s research, very few retirees experience a catastrophic healthcare shock. “The likelihood of experiencing healthcare shocks increases with age, particularly after age 80, but very few retirees saw a permanent increase in healthcare costs after having a large healthcare expense,” he writes.

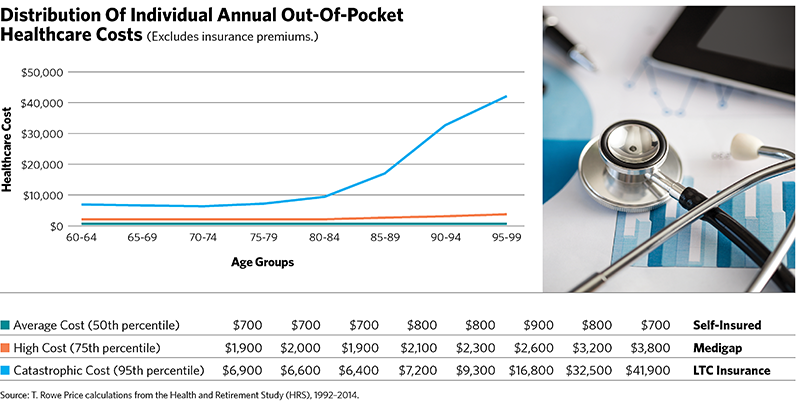

How might financial advisors plan for these costs then? According to Banerjee’s work, an individual in excellent health might budget for the median expenses (see the figure on page 61), while someone with a chronic medical condition might use the 75th percentile as their guideline and those in poor health might use the 95th percentile.

And how might a client pay for those long-term-care costs and healthcare shocks? Banerjee suggests the following: “One might think about self-funding the average costs, using Medigap policies to safeguard against high costs and purchasing long-term-care insurance to protect themselves from catastrophic cost scenarios.”

Kuster also thinks of long-term care as a separate risk. “It is important to address the risk of long-term-care expenses and the potential for an increase in ongoing healthcare-related expenses when evaluating each unique financial plan,” he says. “For many retirees, there is not one ‘right’ solution that removes all the risk.”

Robert Powell, CFP, RMA, is an award-winning financial journalist whose work appears regularly on MarketWatch.com, USAToday.com and TheStreet.com. He is also the editor and publisher of Retirement Daily on TheStreet and co-founder of finStream.tv.