Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Chapter 2 of Wade Pfau’s new book, Retirement Planning Guidebook: Navigating the Important Decisions for Retirement Success.

The biggest risk for retirement is not knowing how long you will live. A new 65-year-old retiree may live anywhere from another year to more than 40. If you live longer, how long will your retirement plan need to support your budgeted expenses? Will you have the resources to sustain spending over that longer lifetime?

A long life is wonderful, but it is also costlier and a bigger drain on those resources. Half of the population will outlive what the statistics say they will, and our lives will only get longer as science finds new ways to keep us healthy. And some people may fear outliving their resources even more than they fear death. That can create a paralyzing effect when it comes to their retirement spending.

Moshe Milevsky coined the term “longevity risk aversion” to describe how people feel about outliving their retirement assets. Beyond mortality statistics, this aversion is what will drive a retiree’s decision about an appropriate planning age. Those with greater fear of outliving their wealth will try building a financial plan that can be sustained to a higher age, one they are much less likely to outlive.

Some people decide to “front-load.” They think it’s best to enjoy a higher standard of living and spend money while they can early in their retirement, and then make cuts to their spending later when they need to. Then there are others who “back-load.” They’ve taken into account that they’ll live a longer life, assume their current plan won’t get them where they need to be, and thus either spend less money early on to stretch their assets—or turn to products with lifetime income protections. These people do not want to reduce their standard of living at advanced ages or be a burden to their children.

This is the trade-off: either live a more robust lifestyle today by accepting a shorter planning horizon or protect your lifestyle in a longer future by spending less today. People must determine how little spending they are willing to accept today so they won’t have to deplete their assets to live a longer life. At the same time, as they worry more about outliving their assets, they’ll find annuities with lifetime income protections more attractive. While the annuity-based cost for lifetime income remains the same, people also are going to want more in assets to feel comfortable living longer.

What’s the best way to choose a planning age? When determining longevity, it may seem natural to base calculations on the aggregate U.S. population, but clear socioeconomic differences have been identified in mortality rates. Higher income, wealth and education levels correlate with longer life spans.

It may not be that more income and education cause people to live longer, but perhaps there are underlying characteristics—that some people are able to enjoy a more long-term focus, and that, in turn, may lead them to seek more education and to practice better health habits. The very fact that you are reading this somewhat technical article about retirement income suggests you probably have a longer-term focus and should at least expect to live longer than the average person (accidents and illnesses aside). And that means mortality data based on population-wide averages are underestimating your potential longevity.

It is also important to keep in mind that while life expectancy at birth is a more familiar number, it is of little relevance for someone reaching retirement. If you have reached 65, obviously you did not die earlier. But that’s actually important information. As you age, your subsequent life expectancy increases. The remaining number of years one can expect to live decreases, but not on a one-to-one basis with age. (We don’t say that 90-year-olds have a negative life expectancy, for example.) These mathematical oversights lead individuals to further underestimate how long they may live in retirement.

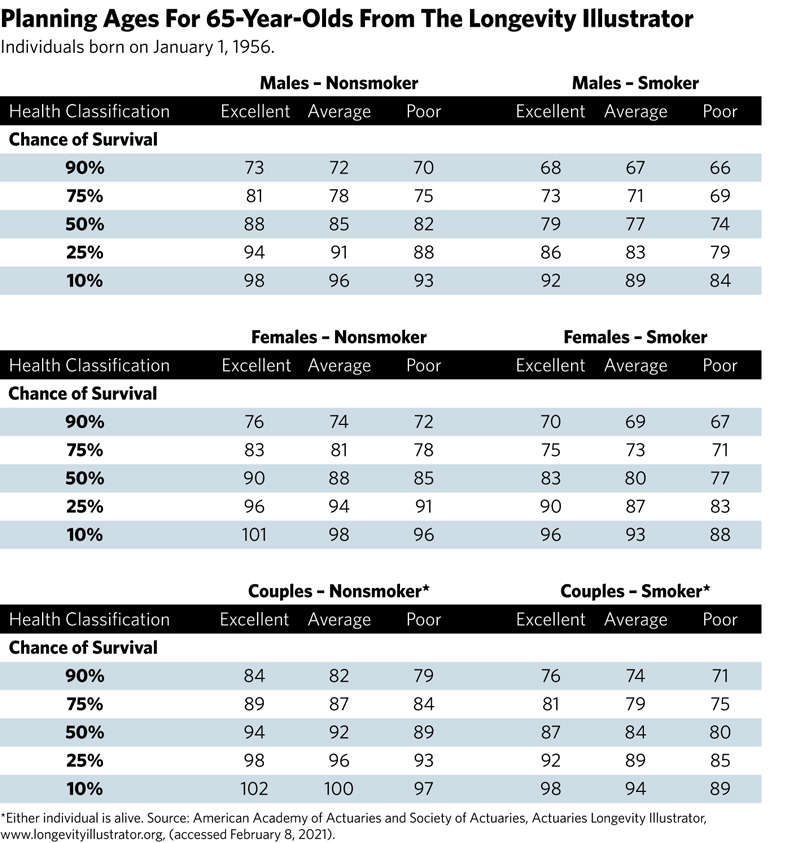

There are tools available that provide more precise longevity estimates for people depending on their circumstances. Some tools ask questions about your family’s history and current health to be more precise. But there’s a simpler tool that offers a longevity estimate in minutes and without cost. It’s called the Longevity Illustrator, and it was developed by the American Academy of Actuaries and the Society of Actuaries to help users develop personal life expectancy estimates by answering a few questions about their age, gender, smoking habits and overall health (it can be found at www.longevityillustrator.org). It’s a simple way to fine-tune your longevity estimates.

The table offers sample cases for 65-year-olds using their health assessment and smoker status. For example, a nonsmoking 65-year-old female in average health who is willing to accept a 10% chance of outliving her financial plan would need the plan to work until she’s age 98. For a male with the same traits, the age is 96. If these two were married, the new 10% chance of survival rises to age 100 for the survivor. That’s because, with two people, the probability that at least one of them is still alive at an advanced age is higher than it is for just one person alone, as now there are two chances they could survive to that age.

In 1994, William Bengen chose 30 years as a conservative planning horizon for a 65-year-old couple when he discussed sustainable retirement spending. At the time, he assumed it was unlikely that either one of the partners in a couple would live past 95. But as mortality improves over time, that time horizon has become less conservative, especially for nonsmokers in decent health. In fact, we can see that the 50th percentile of longevity for a nonsmoking couple in excellent health is age 94. This means 95 is much closer to a real life expectancy. Twenty-five percent of the couples will see one member live to age 98, and 10% of them will still see someone living at age 102!

We can now return to the question of choosing a planning age. This is a choice every person has to make for themselves, using objective characteristics in their assessment: their gender, smoking habits, health status and history, family health history, and other socioeconomic characteristics that correlate with mortality. They will also have to answer more subjective questions: How do you feel about outliving your investment portfolio, and what would be the impact on your standard of living if you outlived it?

With the Longevity Illustrator, these subjective factors can point to which percentile of your estimated longevity distribution to use. As a general starting point, the 25th percentile survival ages may be more applicable to people who prefer to “front-load” their retirement, while the 10th percentile survival ages may be more applicable to those who want to back-load. One could consider going more extreme in either direction, but these values provided by the illustrator are reasonable anchor points. Either this or a related tool could also be used if your age falls outside the numbers shown in the exhibit and you’d like to get more appropriate estimates for your personal circumstances.

Wade D. Pfau, Ph.D., CFA, is the curriculum director of the Retirement Income Certified Professional program at The American College in King of Prussia, Pa. He is also a principal and director at McLean Asset Management and RetirementResearcher.com. His book, The Retirement Planning Guidebook, is designed to help readers navigate the key financial and non-financial decisions for a successful retirement. The book includes detailed action plans for decision-making that can assist advisors and their clients.