There’s no shortage of research showing how investors are often their own worst enemies, sabotaging themselves by making emotional decisions or resorting to market timing and performance chasing (Source: 2018 Dalbar Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior).

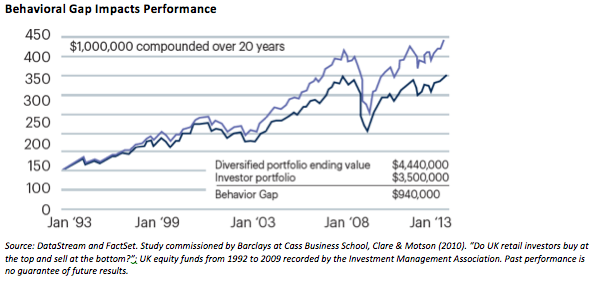

Industry analysis shows this type of behavior can reduce investment returns by 1–2% a year on average—a “behavioral gap” that would compound to a 21% shortfall compared to a diversified buy-and-hold strategy over a 20-year period, as shown in the following chart (Source: “Behavioural Finance Matters.” (n.d.) Barclays Research).

Fortunately, there’s also evidence that working with a qualified financial advisor can help investors avoid some of these behavioral pitfalls. One study, for example, found that investors working with a human financial advisor boosted their investment returns by 3% a year (Source: Kinniry, Francis et.al. “Putting a value on you value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha,” September 2016, Vanguard research). About half of this benefit came from “behavioral coaching,” which the study identified as the most influential action an advisor can take.

The fact that investors don’t necessarily see the need for this type of help—which may not be surprising, given most people don’t like to think they’d fall prey to their emotions—presents a marketing challenge as well as a call to action. Advisors can add value to their businesses by educating their clients on ways to avoid behavioral investing traps, and reinforcing positive behaviors that will pay off in the long run.

Behavioral Traps Can Derail Investment Progress

Advisors may be able to help improve client outcomes and satisfaction by educating clients about the role emotions and cognitive traps can play in investing. Research firm Dalbar (Source: 2018 Dalbar Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior) outlined several of these negative tendencies, including loss aversion, herd mentality, anchoring (locking in to an initial impression or piece of information), endowment (emotional attachment to an investment), and familiarity bias (e.g., investing in a stock because you buy the company’s products). But two of the biggest problem behaviors they identified were:

• The temptation to leave the market during volatile periods.

• Engaging in short-term market timing.

These errors can prevent investors from following through on long-term strategies. In fact, according to Dalbar’s research, investors seldom stay invested in one equity mutual fund for more than four years, on average. Holding periods were even shorter for fixed-income funds, something that suggests risk aversion isn’t the only reason for this restlessness (Source: Ibid). Other factors that could be at play include investors’ overconfidence in their ability to predict market changes, or their attempts to chase performance.

Such missteps can prove costly, as advisors know even one month of bad decision-making—such as missing out on a big market rebound—can potentially derail years of sound decision-making.

How To Promote Sound Investment Behavior

Helping clients curb their emotions and biases is a powerful way to deliver value. This requires not only understanding, but speaking the language of emotions and motivation, while having strategies in place for when client emotions are high. Here are a few ways you can improve your business by helping clients avoid investing traps:

• Be responsive. According to a 2017 investor study, failure to respond promptly to phone calls was the number one reason investors fired their advisors. Clients often call when they are anxious and looking for reassurance, and if they don’t get it from you they may turn to another advisor.

• Acknowledge emotions. Rather than assuming the role of the “expert” and jumping in with logical arguments, listen to your client’s concerns and then mirror them back so the client feels heard. This can help reduce emotional reactions and make a client more receptive to advice.

• Focus on the big picture. Every client has a “touchstone” that drives them to invest and exchange short-term rewards for long-term security—maybe it’s a satisfying retirement, starting a business, or helping their child avoid college debt. Once you know that touchstone, you can return to it during critical situations, showing how different choices could bring the client closer or farther away from their ultimate goal.

• Change the frame of reference. While investors tend to focus on one-year returns in normal times, anxiety during volatile market periods may shorten their frame of reference to daily or even hourly market performance (Source: “Behavioural Finance Matters.” (n.d.) Barclays Research). You may be able to ease frayed client nerves by shifting the focus back to long-term returns—for example, show charts of five-year (or longer) rolling returns, which will smooth many of the shorter-term bumps in the road.

Understanding A Client’s Emotional Needs And Risk Tolerance

Because a person’s attitude toward risk can be shaped by everything from childhood experiences to their profession, advisors need to work directly with clients to better understand how they really view the trade-off between risk and return.

While risk surveys and risk-tolerance tools may help determine basic investment preferences, they’re not necessarily strong predictors of how clients will react when market volatility is high, or as loss aversion becomes stronger. Because investors often have difficulty weighing hypothetical trade-offs, consider combining questionnaires with face-to-face discussions about downside risks and priorities that are more relevant to a client’s specific situation and background (Source: Ibid).

Understanding a client’s “emotional style” may help you anticipate some of their potential investing blind spots. Barclays, for example, outlined several emotional styles and the types of investor behavior they imply (Source: Barclays, “Overcoming the cost of being human: Or, the pursuit of anxiety-adjusted returns,” March 2013):

• Engagement. High-engagement clients take an active role in researching investments and monitoring performance, which can translate into a heightened focus on short-term market movements, especially when anxiety is high. At the other end of the spectrum, low-engagement investors may be less reactionary, but also less aware of the need for regular portfolio rebalancing.

• Composure. Low-composure investors are more emotional and may be very anxious when markets are volatile. High-composure clients, by contrast, may be better at keeping a long-term perspective, but harder to pin down for regular portfolio check-ins. But remember, even high-composure investors might can potentially lose their cool during prolonged periods of market volatility, or if they face stresses in other areas of their lives.

• Need for action. Some people respond to stress by becoming more deliberate, while others are driven drive to act. Advisors may be able to address the reluctance of deliberate investors to act through counsel and strategy. For clients who lean toward action, you might consider incremental portfolio changes to accommodate their need to “do something.”

• Willingness to delegate. Some investors require greater control over their investments, especially in stressful market conditions, and it may be harder for them to delegate decision-making to their advisor. This tendency can carry risks if investors aren’t aware of their blind spots.

• Trust in experts. Some clients have a deep respect for the skill of active managers and may be more interested in specific strategies to manage risk. Others who are more skeptical about active management may be a better match for buy-and-hold index funds.

Anticipate Pitfalls, And Reinforce Productive Behavior

Once you have a better appreciation of how client goals, risk tolerance, and emotional style intersect, you’ll be better able to anticipate their likely investing pitfalls and develop proactive strategies to curb them.

For example, low-composure, low-risk clients may be prone to loss aversion, familiarity bias, and endowment. Advisors may need to invest more time in education while considering interim measures to lower reluctance to change. Low-engagement, high-composure clients with a willingness to delegate may be happy to offload decision-making to professional managers or a managed account if they recognize the limitations this may involve.

Behavioral science argues that if a client isn’t taking our advice, we may not be addressing underlying emotional issues—such as fear of loss or anchoring. We may also have failed to convince the client that change is not only necessary, but doable.

It all boils down to knowing your clients—and understanding what makes them tick as individuals. If you do, you can help them curb their self-defeating investing tendencies, encourage their positive behaviors, and add value to your business in the process.

Matthew Wilson is head of E*TRADE Advisor Services, where he oversees E*TRADE’s technology solutions, custody services and referral network for independent registered investment advisors.