There are potential pitfalls regarding efforts to increase taxable income as a part of managing taxes for long-term efficiency in retirement. These pitfalls make the process more complicated as there is more to pay attention to than just the federal or state income tax brackets. Taxable income can uniquely generate a need to pay taxes on more of Social Security benefits and can raise Medicare premiums. It can also trigger the net investment income surtax. After 2026, it may lead to phase-outs for personal exemptions and itemized deductions. In special cases, there could also be additional tax deductions and tax credits with income limits that could be lost. For those retiring before Medicare eligibility, taxable income could also impact the availability of subsidies for health insurance coverage. Here we will emphasize a few of these key issues. Perhaps the most important of these for typical retirees will be the Social Security tax torpedo and the Medicare IRMAA surcharges.

The Social Security Tax Torpedo

Having more income can uniquely generate a need to pay taxes on Social Security benefits. Up to 85% of Social Security benefits can be counted as taxable income. The rules for Social Security benefit taxation create what is known as the “tax torpedo.” Once benefits begin, each $1 of additional income from qualified plan distributions and the like will require taxes on that income as well as taxes on up to 85% of a corresponding $1 of Social Security. Wealthier individuals may find that avoiding taxes on 85% of Social Security benefits is impossible, but those with relatively more modest resources might be able to set into motion a plan that can reduce or even completely avoid the tax torpedo for life, while following conventional wisdom strategies could leave them mired in paying more taxes through the torpedo. Presently around 50% of Social Security beneficiaries will pay taxes on at least a portion of their Social Security benefits.

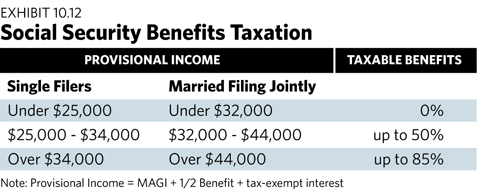

Exhibit 10.12 provides the details for determining how much of Social Security benefits are taxable. The calculation is based on provisional income, which is defined as modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) plus half of the Social Security benefits plus any tax-exempt interest from investments such as municipal bonds. Depending on the publication, this provisional income measure may also be called the combined income or the total income. As well, modified adjusted gross income can mean different things each time it is mentioned in the tax code. In this context, it is generally the components of adjusted gross income listed on the 1040 tax form before including the taxable portion of Social Security benefits. This calculation is what determines how much of the Social Security benefits are taxable, which then allows for the calculation of AGI.

The dollar values in Exhibit 10.12 were set in 1994 and this is one part of the tax code that is not adjusted for inflation. Congress may change these thresholds at some point, but they have been the same for a long time. This means that over time more and more Americans will pay income tax on their Social Security benefits unless they have built up large non-taxable reserves. The upper thresholds for triggering taxation on 85% of benefits are $34,000 for single filers and $44,000 for joint filers.

Calculating taxable Social Security benefits is complex because of these loopy formulas. You do not know your AGI until you know how much of your benefit is taxed, but you do not know how much of your benefit is taxed until you know your AGI. The amount of Social Security benefits that are taxable is calculated as whichever of these three calculations provides the smallest amount:

1. 85% of Social Security benefits

2. 50% of Social Security benefits plus 85% of the amount of provisional income that exceeds the second threshold ($34,000 for singles and $44,000 for joint filers)

3. 50% of provisional income beyond the first threshold plus 35% of provisional income beyond the second income threshold

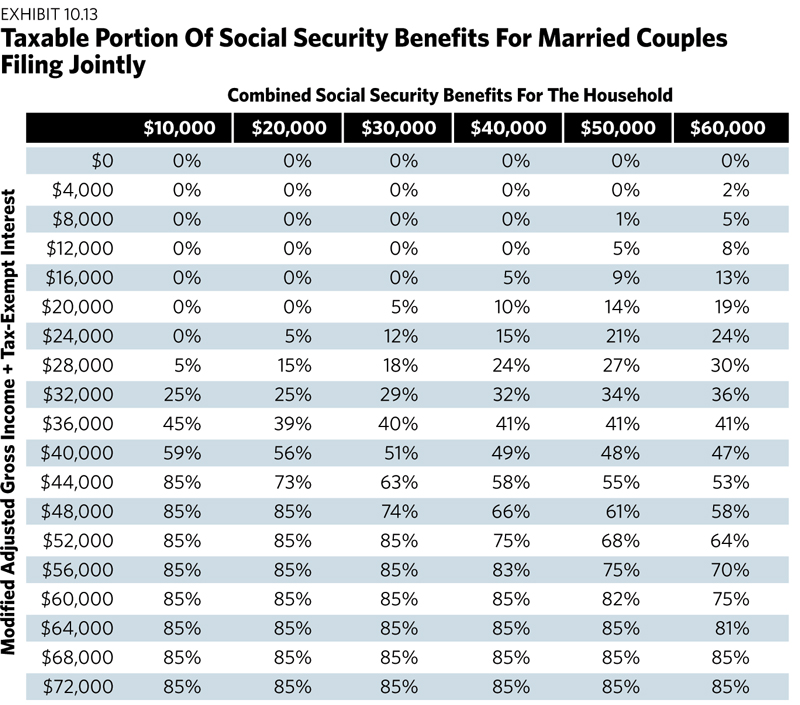

These three calculations can create results that may not be intuitive. It also becomes difficult to connect taxable income directly to the marginal tax rates because the results vary by amount of Social Security benefits. There is not just one tax torpedo; its shape is different for different amounts of Social Security benefits. To provide a sense about this, Exhibit 10.13 shows the taxable portion of Social Security benefits for couples who are married filing jointly. The results are shown for different components of the provisional income (Social Security benefits and everything else). Perhaps the most counterintuitive outcome relates to how the taxable portion of Social Security benefits can decrease as the Social Security benefit increases for different levels of MAGI and tax-exempt interest. This is because the taxable portion of the benefit is not growing as fast as the benefit in those cases where the 85% rate is playing a role.

For Exhibit 10.13, the tax torpedo is at work in any case that taxable Social Security benefits are greater than 0% and less than 85%. When the taxable portion is still 0%, a dollar of additional income does not trigger tax on Social Security. Once the taxable portion becomes 85%, then a dollar of additional income does not trigger more Social Security taxes. But for the range in between, the tax torpedo is at work as more income triggers not just taxes on that income but also taxes on more Social Security benefits.

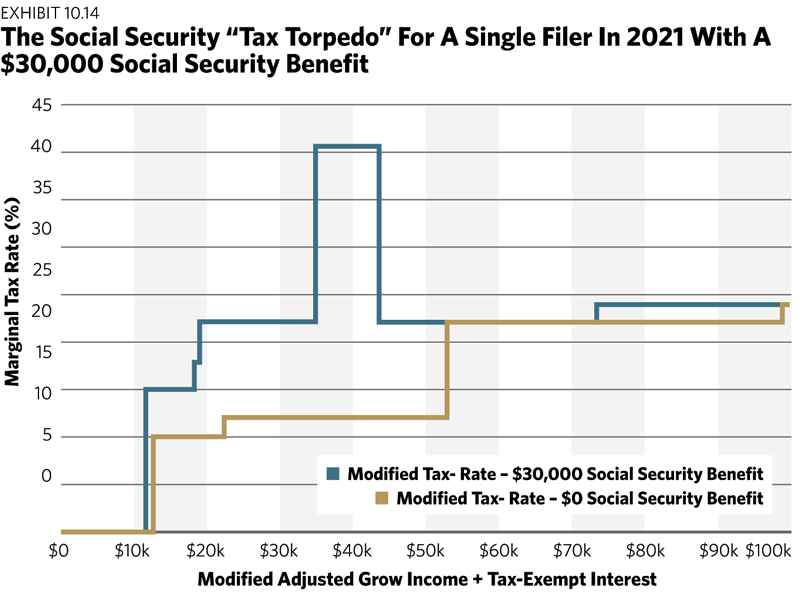

Exhibit 10.14 provides a visual illustration of the tax torpedo for Social Security. In this example, we consider a single filer in 2021, and the assumed Social Security benefit is $30,000. The exhibit plots the MAGI plus tax-exempt interest against the marginal tax rate on $1 of additional income. I will simply call this amount MAGI to avoid having to keep writing “plus tax-exempt interest” every time as well. When the liMAGI reaches $11,700, the marginal tax rate jumps to 15% (this is a 10% federal tax bracket and a trigger of 50% of a Social Security dollar becoming taxable). It jumps to 18% at $18,334, 22.2% at $19,000, and 40.7% at $34,987. It then drops to 22% at $43,706. The MAGI of $43,706 is the point which serves as the upper limit of the tax torpedo with the $30,000 benefit, as now 85% of Social Security is taxed. Subsequent increases in taxable income do not also cause more Social Security taxation. With this benefit, a MAGI of $43,706 represents an AGI of $69,206 with 85% of Social Security added. With a standard deduction of $14,200 for single filers over 65, this represents a taxable income of $55,006.

For tax bracket management, the MAGI of $43,706 becomes an important threshold where there can be extra advantages to stay below it as possible. Otherwise, once getting past this threshold, taxpayers then experience a range where the marginal tax rate is back down to 22%. Understandably, it can be very clunky to move this discussion back and forth between MAGIs, AGIs, and taxable incomes, but at least I hope this discussion has helped to provide a sense about how this tax torpedo can uniquely increase marginal tax rates for retirees as income triggers taxes on itself as well as on more of Social Security.

Social Security taxation creates a case for more than just tax bracket management; it also can add greater after-tax value for delaying Social Security benefits. If one is already retired at age 62, delaying Social Security benefits to 70 could help to provide a foundation for making more Roth conversions before Social Security benefits begin, which could then help keep taxable income lower after age 70 so that Social Security then does not experience as much of the tax torpedo. If Social Security is delayed until age 70, then pre-70 taxable income is reduced. Those waiting to age 70 will have more opportunity to conduct Roth conversions and realize long-term capital gains on taxable accounts at lower tax rates. This will also help to reduce taxable income later after benefits begin. Subsequent Roth distributions do not count when determining how much of Social Security is taxable. Those with the capacity to get a large portion of their IRAs converted to Roth accounts prior to beginning Social Security could enjoy substantial tax improvements. Not only will Social Security benefits be larger, but less, or at least a smaller percentage, of those benefits count as taxable income. These strategies may also help later in retirement to lower the amount of RMDs, to increase the cost-basis for taxable accounts, and to create less pressure to make taxable withdrawals to meet retirement spending needs. Social Security delay frequently complements strategies to support more after-tax spending power.

The tax torpedo can apply for couples as well, and its specific shape does depend on the level of Social Security benefits. The torpedo has the biggest impact when it is adding Social Security taxes on top of the 22% tax bracket, getting the marginal rate up to 40.7% for a portion of income. If the old tax code returns in 2026, the tax torpedo could impact the 25% tax bracket, which would amplify the marginal tax rate to 46.25% with Social Security’s impact included.

That is not even the whole story. These tax rates could be even higher if there were long-term capital gains that further get pushed from the 0% tax bracket to the 15% tax bracket as Social Security becomes taxable. For this to be relevant, the household would need to still be in the 12% tax bracket and in a range where a dollar of income is taxing 85% of a dollar of Social Security. If this also then pushes $1.85 of long-term capital gains from the 0% to the 15% tax bracket, then suddenly the marginal tax rate is 49.95%. With the tax rates scheduled to return in 2026, the 12% tax bracket becomes 15%, which then increases the overall marginal tax rate to 55.5% for this perfect tax storm. Retirement tax rates will not always be lower in retirement, especially when a dollar of income leads to tax on that income, tax on more of Social Security, and tax on more of long-term capital gains or qualified dividends.

Increased Medicare Part B and Part D Premiums

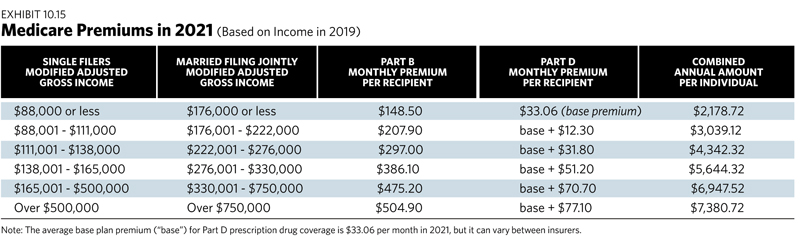

Another part of the tax code that can create tricky planning implications relates to how Medicare Part B and Part D premiums are determined. This is known as the Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts (IRMAA) for Medicare premiums. The level of premiums paid depends on modified adjusted gross income, which in this context is defined more simply as adjusted gross income plus tax-exempt interest. Note again, as with Social Security, that while tax-exempt interest is not taxable, it can generate higher taxes on other sources of income. An additional issue for Medicare, though, is that the relevant measure of MAGI is from two years prior, which is what you have stated on your prior year tax returns. For example, determining Medicare premiums in 2021 means using the MAGI from 2019 included on your 2020 tax forms. For those starting Medicare at 65, this means that tax planning begins accounting for impacts on Medicare premiums at age 63. For those experiencing life-changing events that lower current year MAGI relative to two years prior, which does include retiring, it is possible to file a petition with form SSA-44 to have a smaller premium applied. It is important to note that Roth conversions are not considered as a life changing event and any higher premiums a Roth conversion generates should be viewed as an additional tax.

Exhibit 10.15 provides the details for 2021 Medicare Part B medical insurance and Part D drug coverage. It shows the MAGI income thresholds for a single and for a married-filing-jointly couple as the associated monthly premiums and combined annual values. These are per-person premiums, which doubles the cost for a couple who are both enrolled in Medicare. The costs for Medicare can increase in quite noticeable ways at higher income levels. And it is important to understand that these thresholds are firm. A single person with a MAGI of $88,000 would experience annual premiums of $2,179. With one more dollar of income ($88,001), the annual premium jumps by $860 dollars, representing an 86,000% marginal tax rate on that dollar. This effect gets even larger at other thresholds, and with couples the premium jump is multiplied by two. This is a more extreme type of tax torpedo, and those who are using tax bracket management as part of tax planning should take care to make sure that the MAGI does not exceed a particular threshold by even $1. Leave yourself a buffer for surprises with tax projections that get you close to any of these thresholds. Because these tax brackets are significantly higher than with the Social Security tax torpedo, this issue will affect fewer retirees, but it is important to monitor for Roth conversions.

The Retirement Planning Guidebook is designed to help readers navigate the key financial and non-financial decisions for a successful retirement. The book includes detailed action plans for decision making that can assist advisors and their clients.

Wade D. Pfau, Ph.D., CFA, is the curriculum director of the Retirement Income Certified Professional program at The American College in King of Prussia, Pa. He is also a principal and director at McLean Asset Management and RetirementResearcher.com. His book, The Retirement Planning Guidebook, is designed to help readers navigate the key financial and non-financial decisions for a successful retirement. The book includes detailed action plans for decision-making that can assist advisors and their clients.