As interest rates remain at rock-bottom levels, investors seeking higher yields are piling into bond funds. During the first seven months of 2012, those funds had seen net inflows (sales, adjusted for redemptions and exchanges) of more than $197 billion, while stock funds leaked more than $40 billion of investor money.

The mad dash to fixed-income securities worries Mark Freeman, manager of the Westwood Income Opportunity Fund. "I'm a little concerned about the timing of all these inflows," he says. "There are better income-producing investments out there."

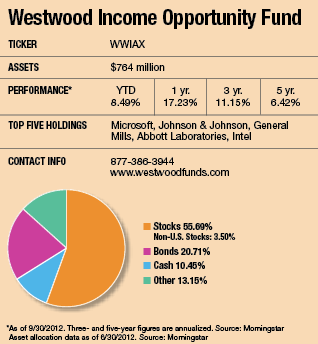

As its name implies, the seven-year-old fund isn't tethered to bonds in its quest for yield. Instead, Freeman and his team diversify the income equation with eight asset classes that include dividend-paying stocks, bonds, master limited partnerships, preferred stocks and publicly traded real estate investment trusts.

Although the fund emphasizes a diversified income strategy, growth is also important here. "Our goal is to earn attractive total returns and maintain a low volatility profile," he says. "The fact that the securities in the portfolio offer high yields means we don't have to be overly aggressive on the growth side."

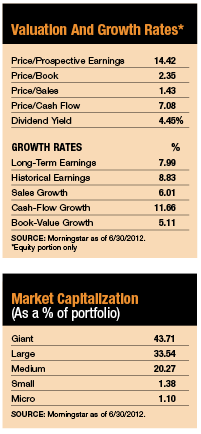

The combined yield of the securities in the fund currently clocks in at around 4%, near the low end of its historical 4% to 6% range. "If you add in some modest capital appreciation of 3% to 5% a year, that's an attractive total return," says the 44-year-old manager.

Freeman, who started his career as a fixed-income analyst, adjusts the fund's asset allocation to where he sees the best values, and these days bonds play a much less important role in the portfolio than they did in the past. According to the latest fact sheet, they account for just 21% of assets, whereas they made up half the fund at the end of 2008. Dividend-paying stocks account for 41% of the portfolio, after they accounted for only 11% four years ago.

"Our allocation strategy is driven by where we are seeing opportunities, and just as important, where we do not," he says. "We believe income-producing stocks, particularly in the large-cap space, are offering the most attractive opportunities."

The shift away from bonds and the move toward dividend-paying blue chips began picking up speed a couple of years ago, when Freeman took note of the increasing number of companies whose dividend yields were higher than their 10-year corporate bonds. "To me, that was a clear indicator that informed professionals had a lot of faith in a company's creditworthiness," he says.

"At the same time, it was also a signal that the stocks were a better value than the bonds."

Freeman sees ample evidence that dividends will rise and stock prices will strengthen in the coming years. With the cash on corporate balance sheets near their historical highs, some companies have ample war chests to boost their dividend payments.

At the same time, payout ratios (the percentage of earnings paid as dividends) are near historic lows, an indicator that there's plenty of room for payout expansion. Companies have recognized the increasing importance of dividends to investors, and over the next 20 years that trend will continue as the number of people over age 65 seeking income-producing investments doubles.

The trends in executive compensation could also have a positive impact on stock prices. Twenty years ago, company managements were paid largely in stock options. Today, companies are more likely to dole out restricted stock, so managers have a vested interest in paying out and growing dividends over time.

Even if the favorable 15% tax rate on dividends expires next year, the demand for these payouts should remain solid, he says. Many dividend payers are held in tax-deferred accounts that won't be hurt by the tax increase, which would likely affect those earning more than $250,000 a year. And with large cash balances on corporate balance sheets, companies are in a good position to soothe some of the tax pain with rising dividend payouts. "With investor need for income and the ambiguous benefit share buybacks give to investors, dividend payouts would likely keep rising even with higher tax rates," he says.

While rising interest rates could make bonds more attractive to new investors, Freeman points out that they usually signal a strengthening economy, which boosts dividends and stock prices. According to the firm's study of the last 40 years, dividend-paying stocks have actually outperformed their non-dividend counterparts during periods when inflation and interest rates rise.

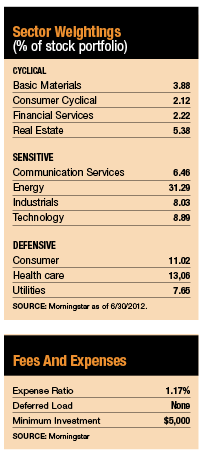

Still, the stocks with some of the juiciest yields, such as utilities, aren't on his buy list. That's because they have a fairly high exposure to interest rate risk; investors tend to abandon them when interest rates rise and bonds look more appealing. Their dividend increases aren't as robust as some other companies', and the dividends also absorb most of their earnings.

Instead, Freeman prefers stocks with strong but not spectacular dividend yields that have good prospects for dividend growth and capital appreciation. Such companies have much lower payout ratios than the average stock, so there's a better chance they will grow their dividend payouts over time at an inflation-beating pace.

Fund holding Microsoft is such a company. While its 10-year bond yields about 1.8%, the stock's dividend yield is 2.7%. With a low payout ratio of 26%, the technology giant is in a good position to increase dividends going forward. The stock sells at a reasonable 10 times projected earnings, and Freeman says earnings growth should come in at about 10% a year.

Another large technology company among the fund's holdings, Intel, is priced at a reasonable 10 times forward earnings. Its dividend yield is 3.7%, substantially higher than the 2.3% yield on its 10-year bond. The company has raised its dividend an average of 14% annually over the last five years and has a healthy payout ratio of 35%. Freeman says an expansion into laptops and smart phones should help the company produce earnings growth of around 8% next year.

Health-care companies such as Johnson & Johnson and Novartis offer yields close to those of utilities, but are a better deal, Freeman says, because their stocks offer a superior shot at appreciation. "A health-care company with a 4% dividend yield sells at 10 times earnings and has prospects for high-single-digit earnings growth next year, while a utility stock offering about the same yield sells at 16 times earnings and has little or no potential for earnings growth."

About 8% of the fund's assets are devoted to preferred stock. As a hybrid stock-bond investment, preferred stock pays a specific dividend that does not change. It is higher in the securities pecking order than common stock, because if a company defaults, holders of preferred shares are ahead of stockholders (though behind bondholders) for payment. Issuers must also pay preferred dividends ahead of common stock dividends. The preferred stock of Freeman's longtime holding Bank of America has offered a reliable 6.5% to 7% yield over the years and has been less volatile than the bank's common stock. Recently, the fund added to the portfolio preferred stock of BB&T Corporation, a large financial services holding company.

Master limited partnerships such as Western Gas Partners (WES) and Plains All American Pipeline (PAA) account for another 8% of Freeman's portfolio assets. These companies, which trade as "units" on an exchange, must earn 90% of their revenue from activities related to commodities, real estate or natural resources. They are both involved in the storage and transportation of natural gas and both produce yields of about 6%. The two MLPs also both stand to benefit from increasing spending on energy infrastructure and a pickup in merger and acquisition activity in the sector.

The fund's whittled-down bond stake consists mainly of investment-grade corporate securities, since Freeman doesn't want to compound the risk the fund is already taking in other asset classes. He had a relatively hefty stake in Treasury securities a few years ago, but began selling off those positions as their yields shriveled in comparison to corporate bonds.

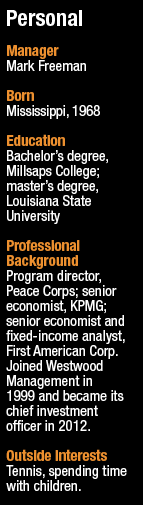

Bonds of all stripes are very familiar territory to Freeman, who started his career as a fixed-income analyst at a regional bank. When the Westwood Management founder Susan Byrne hired him nearly 14 years ago, she recognized that many of the skills needed to evaluate bonds also translated well in the stock world. "Fixed-income investing is all about evaluating risk, and when you're looking at equities you're basically doing the same thing," he says. "She understood that."

After sharing the role of chief investment officer with Byrne since the beginning of 2011, Freeman assumed full responsibility earlier this year. Byrne, now chairman of the firm's board, no longer makes day-to-day investment decisions but remains active in the firm's broader policy decisions.

The orderly transition is somewhat unusual for a mutual fund firm that's been managed for decades by the person who founded it. Often, those at the helm of such funds manage them well into their late 60s and aren't open to discussing retirement plans with the press. Freeman says that as a publicly traded company, Westwood is obligated to shareholders to ensure a smooth transition. For investors, he says, it's a signal that "we have a sustainable process that transcends one individual."