It should be no surprise that Bitcoin sold for over $44,000 this week, more than double its March 13 price. Going back to 2014, it has taken the cryptocurrency an average of nine months and 21 days to double; the milestone came 28 days early this time.

What is mildly surprising is that Bitcoin doubled without ever falling below its March 13 low. On average, it has dropped 27% between doublings (that is, if it starts from $1,000, it drops to $730 before trading above $2,000) and it has dropped as much as 83% (trading for $170 before going to $2,000).

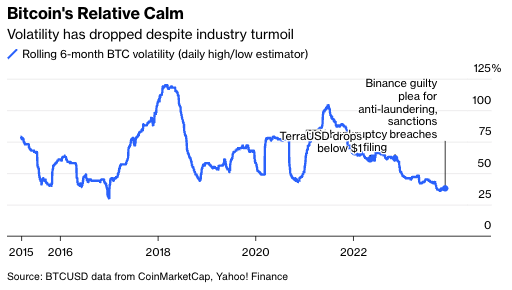

Even that is mostly old news as volatility has steadily declined since a Covid-era peak. Annualized volatility has been 50% over the last two years, no higher than many large technology stocks. Moreover, this relative calm has occurred over a period with massive scandals, bankruptcies, prosecutions and regulatory fights in crypto.

Does this mean Bitcoin can be invited to the grown-up table at this year’s holiday dinner, to have its own place in standard portfolios?

For most investors the answer is still “no.” Bitcoin has more than enough appreciation potential to attract investors, and its volatility no longer seems to be a disqualification. Issues like secure custody, tax treatment and legality seem mostly solved. But its correlations with other major assets—particularly stocks, currencies and gold—have been unstable, making it hard to fit in, like a left-handed dinner guest.

Back in 2011, I estimated crypto would be 3% of the global economy. As an efficient market investor, I have since kept 3% of my net worth in crypto when volatility was low and when it was high, and when crypto was soaring and crashing. But most investors prefer investments that behave in at least semi-predictable ways to fundamental events and prefer buy-and-hold to constantly responding to price changes. (Disclosure: I also have venture capital investments and advisory relations with crypto companies.)

The original value case for Bitcoin was as a transaction currency. It was far more efficient than the traditional financial system for international transfers, the unbanked and citizens of financially repressive regimes.

Bitcoin also proved convenient for rarely prosecuted crimes like recreational drug sales, prostitution and gambling. Despite a popular myth, it is not a good currency for serious criminal activity such as terrorism or murder-for-hire, because transactions are public and immutable. It’s true they are also pseudonymous—you don’t have to use your real name—but investigators have little trouble tracing individuals via patterns of flows. Serious criminals do better with government-issued cash, assets like gold or diamonds, or privacy-protected cryptocurrencies like Monero or ZCash.

At this week’s Senate Banking Committee hearings, Senator Elizabeth Warren agreed with JPMorgan Chase & Co. CEO Jamie Dimon and other bankers that anti-money-laundering controls should be applied to crypto. While laws can make it difficult to move traditional currencies in or out of crypto for criminal purposes, there is no way to prevent or track direct transfers within privacy-protected crypto, and financial repression to combat money laundering is one of the things that drives people—both honest and dishonest—to use crypto.

This does not matter for Bitcoin, because its use case as a transaction currency unraveled long ago. Radical improvements in traditional finance were a factor as were attacks by governments on crypto use for crimes they usually ignored. But the biggest reason was crypto innovations such as Ripple or Nano, which were far better transaction currencies.

By around 2015, the value case shifted to the “digital gold” argument. Bitcoin would be a value anchor to crypto and used for transferring traditional currencies in and out of crypto, the way gold was a value anchor to paper currencies for centuries, used for settling accounts among central banks.

From this view the value of Bitcoin depends on three things: the ultimate value of crypto projects, the amount of traditional currency moving in and out of crypto, and whether alternative means of providing a banking system for the crypto economy prove superior.

The first, the value of crypto projects, is basically a technology venture investment—lots of exciting ideas that might change the world and be worth trillions; little actual revenue or profit in traditional currency terms.

Traditional currency moving in and out of crypto has been subject to boom and bust, or in crypto-speak, summer and winter. In crypto summer, lots of money flows in, but also lots of crypto people cash out at least some gains. Moreover, people use Bitcoin to move from one crypto project to another. In crypto winter, there is little flow in either direction, thus little demand for Bitcoin financial services.

The least volatile element has been in financial services competition. Bitcoin has rapidly improved its connections with traded public futures and options, efficient borrowing and lending, secure custody and other aspects of a sophisticated modern financial system. If a spot Bitcoin exchange-traded fund is approved by the Securities and Exchange Commission in January, as expected, this will improve matters. Everything people do with stocks and bonds—invest, raise capital, hedge, speculate, exchange, hold—they can do at least as efficiently with Bitcoin, which also offers immediate access to the full crypto economy.

Stablecoins have achieved niche success in comparison. Only Ethereum among other cryptocurrencies has developed any sort of native financial system, and it lags far behind Bitcoin. Attempts by traditional financial institutions to harness blockchain and other crypto technologies also have niche successes, but they do not threaten Bitcoin’s hegemony. Some major attempts to build financial services directly into crypto, like FTX and Celsius Network, collapsed in 2022, and all were tainted by the fallout.

This three-step value proposition explains the unstable correlations.

The market value of crypto projects depends on investor enthusiasm for technology ventures, which has a high correlation to technology stocks. But the enthusiasm for putting money into crypto often has the reverse correlation, with disappointing tech returns sending optimists and risk-lovers to crypto.

The latest doubling of Bitcoin prices seems mostly related to increasing regulatory clarity and tolerance, which does not seem to extend to stablecoins or other crypto. This enhances both the efficiency of the Bitcoin financial and banking system, and insulates it from competitors. Regulatory attitudes are mostly uncorrelated with asset prices.

With no obvious triggers for changes in crypto project successes or enthusiasm for crypto trading on the horizon, the near-term outlook for Bitcoin seems to depend mostly on regulatory news, especially the approval of spot Bitcoin ETFs. Beyond that, there is always the possibility of pullbacks or bumps in the road, especially if there are new crypto scandals.

Competition from stablecoins, traditional finance and crypto-native institutions is near zero, so any progress there can only be negative for Bitcoin. My guess is that the next Bitcoin doubling will be driven by the long-awaited crypto “killer app” that persuades millions of people to learn and use crypto, not just hold or trade it. The other possibility is problems in the traditional financial system—a crisis, increased repression, inflation fears, a credit crunch—will make Bitcoin relatively attractive.

We are close to the time when even very traditional investors, generally skeptical about crypto, should accept that it’s safer to have a small allocation to Bitcoin than to ignore it. Crypto might still all go to zero, but there’s enough potential upside that no exposure is an unbalanced portfolio.

Aaron Brown is a former head of financial market research at AQR Capital Management. He is also an active crypto investor, and has venture capital investments and advisory ties with crypto firms.