A little over a year ago, most observers thought the Federal Reserve would raise interest rates to help ward off inflation in an expanding economy. Investment firms and mutual fund managers cautioned fixed-income investors that they should keep their return expectations in check.

But by spring, fears about rising rates subsided as concerns about sluggish economic growth crept back into the picture. The Fed ended up cutting rates three times, and the 10-year Treasury yield fell to a low of 1.46%. At the same time, de-escalation of U.S./China trade tensions, easing measures by global central banks, and strong investor demand kept bond markets buoyant. By year’s end, U.S. investment-grade corporate bonds posted a return of 14.54%, while the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index saw an 8.72% return.

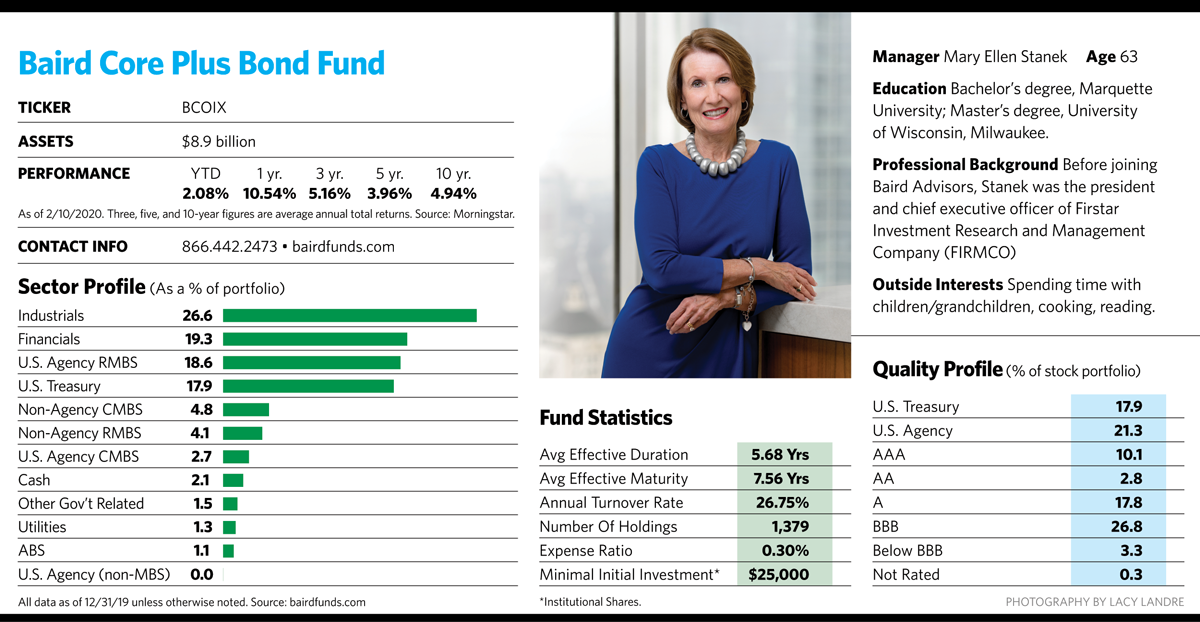

When she looks at the rest of 2020, Mary Ellen Stanek, a 40-year bond market veteran, sees the potential for an equally bumpy ride in an environment of election year uncertainty. “My advice for investors is to keep their seat belts on,” says Stanek, the chief investment officer at Baird Advisors and manager of the $24 billion Baird Core Plus Bond Fund and the $23 billion Baird Aggregate Bond Fund.

Short-term market disruptions could come in a number of fronts, she says. Because presidential candidates have widely disparate views on a variety of issues, including those affecting the economy and taxes, any shift in the political sentiment could have a powerful impact on the financial markets. Trade tensions and global discord threaten to throw a wrench into world economic growth. A growing federal budget deficit could ultimately put upward pressure on Treasury rates, and the current economic expansion, the longest since World War II, could run out of steam.

On the positive side, Baird’s economic outlook calls for the U.S. to experience gradual, albeit subpar economic growth and modest inflation. Global growth likely reached its slowest pace in 2019, and the risk of global recession has diminished. Economic growth in the U.S. should range from 1.5% to 2.5% this year, extending the long expansion.

Given that inflation has persistently run below 2% in the last several years, the Fed would be unlikely to raise rates if things stayed the same. “The Fed will probably be on the sidelines for 2020,” Stanek says, “so we’re looking for that side of the equation to be relatively quiet.”

While economic growth will be sluggish, consumer sentiment, employment and income numbers are decent. Individuals are winnowing down personal debt. Employment is broadening to wider, more diverse segments of the population. And low-wage workers are finally seeing their paychecks increase.

Over the longer term, an aging population around the world should support demand for bonds as investors shift from growth to income needs. Pension plans, insurance companies and other institutional investors with long-term liabilities will also support the market. And while the U.S. government debt burden continues to mount, the issue is unlikely to come to the forefront until after the November elections.

Shooting For Small Wins

Stanek, who has managed both her funds since their 2000 inception, believes that beating the indexes over a long period isn’t about making hefty security bets or picking the next hot issuer. Instead, it’s about navigating the comparative risks and rewards among a vast sea of bonds and issuers, picking sector spots carefully, achieving lots of small wins consistently over the long term and keeping costs low.

She considers her management style to be a hybrid blend designed to track and beat its benchmark consistently over time. On the passive side, the fund maintains the same duration as its benchmark to avoid making interest rate forecasts, a feat that Stanek believes is nearly impossible to achieve successfully. On the active side, the fund’s strategy tinkers with the benchmark yield curve by selecting bonds with maturities and yields that work best.

The active side of the strategy comes into play with its sector allocation and individual security selection, with managers scouting out the best relative values among issuers and individual bonds.

The approach has helped both funds beat their benchmarks consistently over the long term. The Core Plus Bond Fund, which can invest up to 20% of its assets in below-investment-grade securities, has performed better than the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Universal Bond Index over the last three-, five-, and 10-year periods, and since its inception it has ranked in the top 15% for returns in its Lipper peer group. A low expense ratio of 0.30% for institutional shares also provides a tailwind against the competition.

Active management tweaks worked well for the fund in 2019 as institutional shares posted a return of 10.11% while the benchmark posted only 9.29%. The fund has historically favored investment-grade U.S. bonds and the financial sector, which outpaced other parts of the bond market last year and accounted for much of the fund’s outperformance. It also helped that the fund had less than the benchmark did in government bonds, which did not perform as well.

While the rally in investment-grade corporate bonds was good news for the Baird Core Plus fund, it also brought their yields closer to those of comparable duration Treasurys. At the end of 2018, U.S. corporate bonds held a yield advantage of 153 basis points, a spread that ran slightly above its 145 basis point average since 2009. By the end of 2019, the corporate yield advantage had narrowed to 93 basis points, a shift that made it less attractive for investors to take on credit risk.

There is also growing concern among some investors about the increase in the number of issuers that populate the “BBB” market, the lowest tier of investment-grade ratings. Nearly half the bonds outstanding globally have that rating, whereas they represented only 10% of the universe in 1974. The plethora of these bonds raises the odds that billions of dollars in securities could get knocked below investment grade in a recession.

Stanek says the current uncertainty heightens the need for active management, and one way of doing that lately has been to let her Core Plus fund’s overweight position in corporate bonds migrate a bit lower.

“With spreads tighter than last year, we’ve become more selective about picking our spots in the credit market,” she says. “But there are pockets of opportunity. Corporate credit fundamentals remain solid, and it’s still a pretty constructive environment.”

She points out the Core Plus fund has a number of tools at its disposal to control risk. At year’s end, there were nearly 1,400 bonds in the portfolio, which lowers individual security risk. Lower-rated bonds usually have smaller individual position sizes in the portfolio (and shorter durations) than those with higher ratings.

“We look at the portfolio as a whole and try to figure out how the various parts work together,” she says. “The key is finding where we are being paid to take risk, and where we’re not.”

Recent corporate bond purchases that fit her risk-reward profile include Energy Transfer Partners, which builds and maintains natural gas and crude oil pipelines in 38 states. These “BBB-” bonds had a recent yield 195 basis points higher than that of comparable Treasurys. Stanek says Energy Transfer Partners’ bond payments are well-covered by its long-term contracts, and since it’s a midstream energy company, rather than a direct producer, it enjoys a buffer from commodity price fluctuations.

Baird also recently purchased bonds issued by automaker Ford carrying a “BBB” rating and maturing in three years. “We think certain short-dated auto bonds have an attractive risk-reward profile,” she says.

One place she’s not reaching for extra yield is in junk bonds, which can account for up to 20% of assets in the Baird Core Plus fund. Its peak allocation of 12.4% of assets occurred nearly a decade ago. That number stands at around 3% now, well under the benchmark’s weighting.

“Below-investment-grade bonds have seen a significant run, with investors chasing yield,” she says. “The problem is that migrating to high-yield exposure might work on the way in. But those bonds face liquidity issues during periods of market duress.”

Over many years, the fund has been overweighted to the financial sector. Stanek says that’s because access to capital is the lifeblood of banks and other financial institutions. They have an added incentive to keep their credit ratings buoyant. And the heavy price financial issuers pay for credit downgrades means their interests are very closely aligned with those of bondholders. On the other hand, the fund maintains an underweight in agency mortgage pass-through securities because she’s concerned about the valuations and potential price volatility in that sector.