Similar to Russia and Australia, Canada is a vast and—to a large degree—uninhabitable country due to climate and/or terrain. That does not mean it is a desolate country. It is, however, a very small country when you exclude the unlivable areas. Its population is oddly distributed due to this reality.

Geography has played a major role in how the country has developed. It affects national and provincial politics, transportation and trade, and national security and foreign policy. We will also look at how the US exerts a heavy influence in some of these areas.

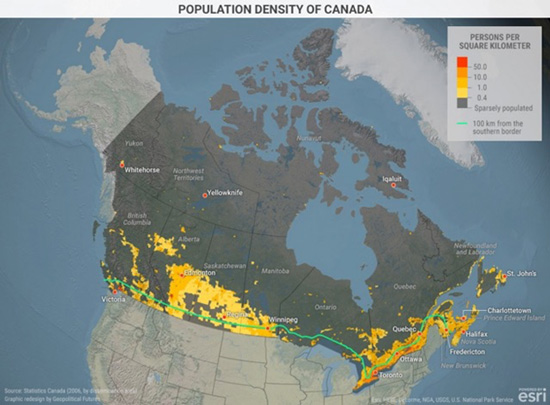

Canada is the world’s second largest nation by area. But with 35 million people, it is only the 39th most populated country and ranks 230th in terms of population density. The map above shows that Canada’s population is clustered in a long and narrow band along its southern border.

George Friedman is editor of Mauldin Economics' This Week In Geopolitics.

This article was originally published at Mauldin Economics.

In fact, a large share of the population lives within 100 miles (160 kilometers) of the US border. The densest population is in the east, running just east of Detroit through Quebec to the Maritime Provinces on the eastern coast. Another populated area, though not particularly dense, runs from Winnipeg to the base of the Canadian Rockies. Notable is the low population in most of Ontario, save for the Toronto-Ottawa corridor.

One crucial geographic feature is the Canadian Shield. It is an area formed mainly of volcanic rock covered with a thin layer of soil.

The Shield—plus a tough climate—has made much of Ontario, Quebec, and other regions difficult to inhabit. This has forced population centers to develop southward.

In addition, the Rocky Mountains run south through western Alberta and much of British Columbia. This is another example of how geography, as well as climate, limits the amount of livable land.

The peculiar geography of Canada has also created inherent internal problems. For example, east-west transportation is heavily concentrated within the narrow population corridor along the US border. For most of Canada, north-south transport into the US is more efficient than routes that don’t cross the border.

Further, its unique geographical features and historical factors have shaped Canada into a confederation, rather than a federation. The provinces, in many areas, have more effective authority than Ottawa. In the extreme, a persistent faction in Quebec seeks to secede from the confederation. Still, political differences aside, the provinces have an interest in staying together.

At different moments in history, though, the economic, political, or security interests of some provinces have relied more on the US than other parts of Canada. At these times, provincial self-interests have led to discord. So, geography poses a significant potential fault line in Canada.

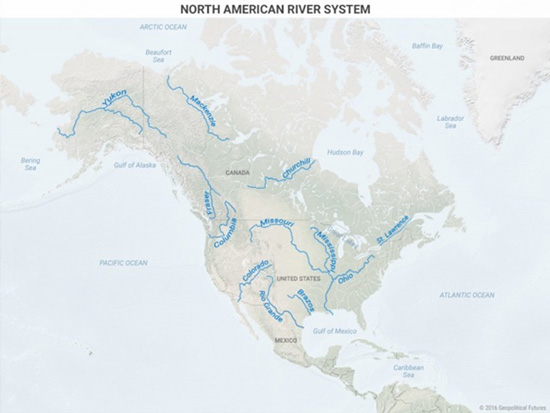

Geography also distinguishes Canada from the United States. There are two components to this distinction. First, as the map above shows, the Canadian Shield is almost entirely in Canada. Only a tiny part of it extends into the US. Second, Canada lies outside the US river transport system.

The most important economic driver in the US through the 19th century was agriculture. What made agriculture a viable business in the area between the Rockies and Appalachians was a vast network of navigable rivers. This network flowed into the Mississippi River. From there it was an easy float to the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean.

This system of waterways created vast wealth in the US. Yet, the way the US-Canada border was drawn west of the Great Lakes meant none of Canada’s rivers run into this highway to the oceans.

The Canadian river system does carry a large amount of cargo for export. Canadian producers can ship their goods to sea ports in Canada, or down south to the rivers. Granted, this is no longer a decisive difference between the two countries, but it was once. Therefore, the Shield and the river system together explain the divergence between the US and Canada.

Today, relations between the two countries are centered on trade. Last year, Canadian exports to the US totaled roughly $310 billion, while US exports to Canada were almost $280 billion. The US is Canada’s largest trading partner. Canada is the US’s second largest trading partner. It’s obvious why the north-south trade partnership is so important.

If we drill into the trade numbers, we see that Canada is a leading importer for many American states.

At the same time, most of the US relies on Canada as its main export market. The only region outside the Canadian orbit is the Southwest, where the primary export destination is Mexico. In other words, although the balance of trade is slightly in Canada’s favor, many individual US states depend heavily on Canada to buy their exports.

Therefore, from a strategic standpoint, Canada’s core interest in the US is to maintain strong economic relations. This is not at risk because it is a shared interest rooted at the all-important local level.

In other areas, Canada’s strategic interests must align with those of the US. There are three reasons for this. First, the well-being of the US is a Canadian national concern. Second, Canada cannot defend itself from a global threat. Third, one look at a map and it is obvious that Canada is exposed to any threat the US is exposed to.

This does not mean that the Canadians are forced to cooperate on all American foreign activities and wars. The US will not break economic relations over these matters, nor is Canada essential to US global activities. But in the long run, the fact is that Canada and the US don’t need a formal alliance. They are joined at the hip.

In extreme situations, Canada has no choice but to align with the US, as its failure is Canada’s failure. In the short term, Canadian cooperation with the US buys it a place at the table when the US considers changes to its actions or strategies. And those shifts can influence Canada disproportionately.

Canada can go its own way only within limits. Not because the US demands it, but because geography has closely linked Canada to the US. This may not be the prevailing view in Canada, where many see more room for maneuver. But Canada is constantly drawn back into reality by the constraints posed by its geography.

An example is the reputed Northwest Passage, which may be opened up due to effects of global warming. The Russians and others are interested in the possibilities this offers. So are the Canadians. But the Canadians cannot afford the cost of a naval fleet capable of a forward defense of their interests should the Russian navy challenge Canadian sovereignty in the region.

If a defensive force that can protect the region is established, it will come from the US Navy. It is a given that this military project, if needed, will be a joint venture. After all, both the US and Canada have identical interests in the passage. And even if a joint military project is unnecessary, both countries will want to use the Northwest Passage.

Last Words

Canada’s strategic interests align with American interests because Canada is heavily integrated with the US. And Canada alone cannot provide a strategic defense against potential enemies. Given Canadian dependence on the US for trade—a less significant partnership to the US due to the size of the American economy—it is clear that Canada has a single overriding strategic interest: maintaining close relations with the United States.

Atmospherics can shift. But the reality remains constant.