The market pundits remain intensely focused on the question of whether the U.S. economy is in or about to enter recession, so we thought a piece on what a recession might mean for the stock market would be of interest. While Friday’s strong jobs report provides more evidence that the U.S. economy is not currently in recession, odds are still perhaps a coin flip or better that one may come in the next year. Here we update changing recession prospects and what that might mean for stocks.

Where Did All The Jobs Go?

Payrolls surged by 528,000 in July and the unemployment rate fell to 3.5%. Moreover, net revisions to the previous two months added another 28,000 jobs to the original estimates. Clearly, these gains further cement the claim that the U.S. is currently not in recession. Job gains were broad-based and especially prominent in sectors such as education, health care, and government. Firms ramped up production and increased manufacturing payrolls by roughly 30,000 in July. New jobs in manufacturing are likely due to improved supply chains, and this sector should continue to add jobs as remaining supply bottlenecks improve.

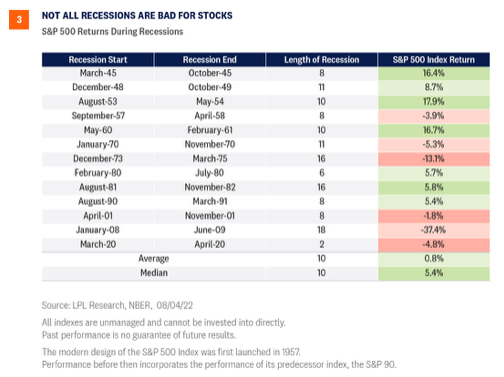

Total employment has returned to pre-pandemic levels in February 2020 but not back to pre-pandemic trends [Figure 1]. We could argue over which is more important, but both tell a specific story about the health of the consumer and the broad economy. Trends give a wider context for the labor market. A lurking risk is those not in the labor force will experience skill erosion and the economy will have downside risk to productivity growth in the coming quarters. Although we are not likely in recession now, risks are rising for next year. The economy needs a stable and productive workforce to handle tighter financial conditions and growing uncertainty about 2023. Despite the risk, the economy could still have a soft landing as the Federal Reserve (Fed) tightens monetary policy to combat historic inflation pressures.

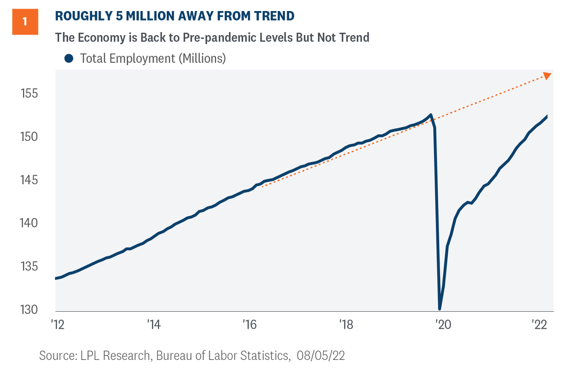

Participation Rates Are Below Pre-Pandemic Levels

The participation rate dipped slightly to 62.1% as the labor force shrunk in July by 63,000 and the unemployment rate fell to 3.5%, a decline of 0.1% percentage point. A nagging concern as the economy pivots from reopening to retooling is the low participation rate. For all age groups, participation rates have not recovered from the pandemic, which is one of the sour notes in an otherwise sweet report. Overall, the July labor force participation rate was 1.3 percentage points below February 2020, and the largest gaps were for those of high school and college age and those 55 years old and up [Figure 2].

The decline in unemployment and the participation rate will frustrate central bankers since a tighter labor market adds inflation risk to the economy. So far, wages have not kept up with inflation. Average hourly earnings rose 0.5% in July after rising 0.4% the previous month. As of July, average hourly earnings were 5.2% higher than a year ago.

Markets are having trouble digesting the implications of the strong labor market in July. The big headline gain in jobs was a surprise and could convince people like San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly that the economy needs another 75 basis point hike at the Fed’s next meeting. All eyes are now on inflation.

Stocks And Recessions

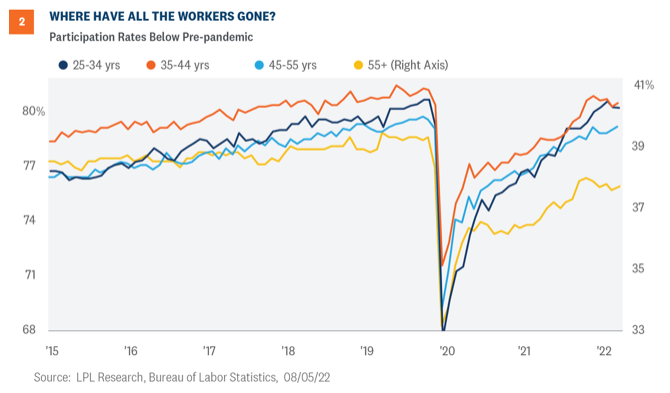

Market strategists and pundits make the relationship between recessions and the stock market seem binary, but each economic contraction is different and has different effects on earnings. That said, it is still instructive to look at what stocks have historically done during recessions to get an idea of potential stock market scenarios.

First, keep in mind that stocks tend to look forward by four to six months and can provide warnings of changing economic conditions. For example, the start of the bear market decline earlier this year told us weaker growth and lower earnings were coming—and stocks certainly got that right. Bigger losses through June sent a stronger signal—that the odds of recession were probably over 50%.