It’s become all too common to attribute the surge in emerging-market assets this year to the cheap cash sloshing around the world courtesy of central banks. But that’s only half the story.

Sure, faced with negative debt yields in many developed countries, investors have cast their nets far and wide to bolster returns, often pouring money into the bonds, stocks or currencies of nations mired in recession.

But some of the most troubled emerging economies and companies in recent years are actually giving money managers reasons to pile in. China is now on pace to hit its growth target, while Brazil and Russia are poised to emerge from their slumps. Developing nations have also boosted their foreign reserves by $144 billion to $9.9 trillion after they sank to a three-year low in March. The more than 800 companies in MSCI’s Emerging Markets Index posted average growth in earnings-per-share of 47 percent in the latest quarter, while profit for members of the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index fell.

“There are signs that things are looking better, or at least less bad,” said Kieran Curtis, an investment director at Standard Life Investments Ltd. in London, which has $350 billion of assets under management. “The stabilization in Brazil and Russia is having a big impact on the aggregated growth rate of emerging markets.”

While yields on developing-nation bonds have plunged 1.25 percentage points since January to 4.23 percent as investors scooped up the debt, they’re still well above much of what you get in places such as the U.S., the Eurozone and Japan. There are about $8.9 trillion worth of bonds with negative yields globally.

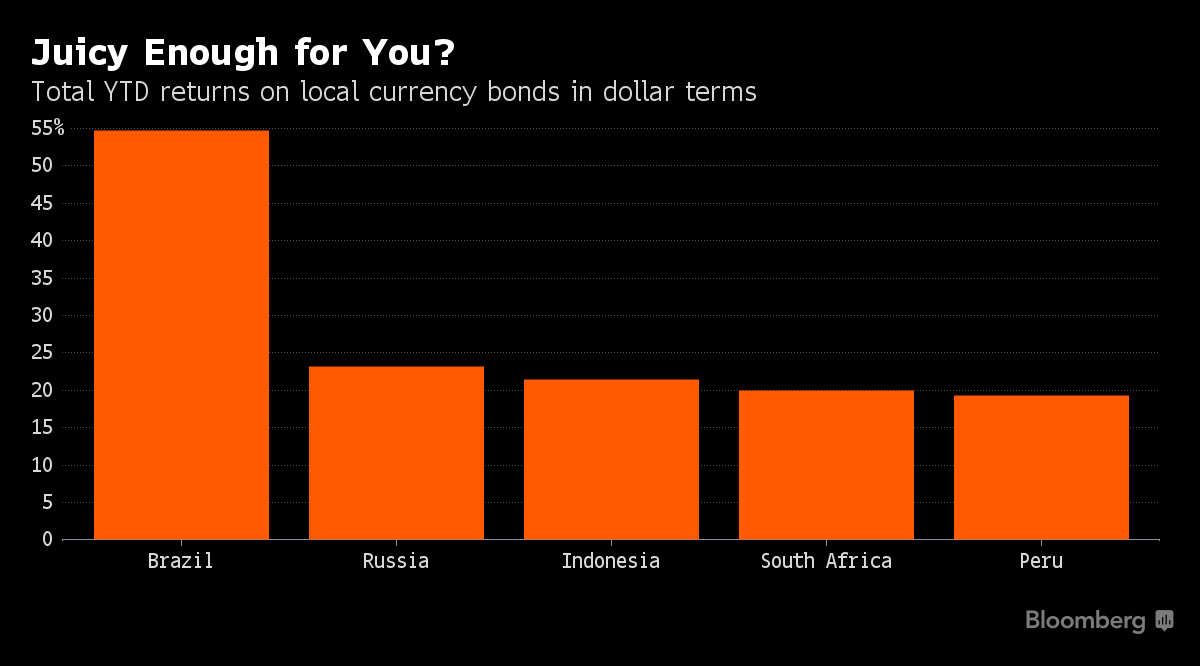

Investors in hard-currency emerging-market debt have reaped average returns of 12.7 percent this year, led by gains in Venezuela and Zambia. Meanwhile, an index of 20 developing-nation currencies has jumped 5.2 percent in 2016, on pace for the biggest surge in seven years. MSCI’s emerging-market stock gauge is up 13 percent this year, almost four times as much as the broader MSCI World Index of developed-nation stocks. An index of emerging-market currencies has gained 4.3 percent this year, on course to end three years of declines.

“It’s safe to assume that yields in emerging markets will continue to come down,” said Jim Barrineau, a New York-based emerging-market money manager at Schroder Investment Management Ltd., which has about $450 billion in assets worldwide. “Fundamentals are improving. Fundamentals always follow liquidity. First we get liquidity flow, then you get the central banks lowering rates, then you get the currencies appreciating, then you get better growth.”

Companies and households in developing nations are starting to reduce borrowing as a percentage of their economies. Excluding China, the credit-to-gross-domestic-product ratio has dropped to 127 percent, from 128 percent at the end of last year, marking the first decline since the global financial crisis, according to data compiled by Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

Emerging-market companies in particular are slashing debt levels that had become increasingly worrisome amid a tumble in currencies in recent years.

Brazilian firms led by state-owned oil company Petroleo Brasileiro SA cut their average net debt to earnings before items to 2.2 times last quarter from 2.6 times a year earlier. Petrobras, as the crude producer is known, shaved $8.9 billion off its balance sheet.

In Russia, the average debt of companies in the MSCI index fell to $8.9 billion in the second quarter from $10.3 billion a year earlier as international sanctions prevented many from issuing new debt. Oil and gas giant Rosneft PJSC alone chopped $8.6 billion of obligations.

The debt-reduction push is one of the reasons emerging-market stocks have soared this year, led by the 63 percent surge in Brazil’s benchmark index in dollars. India’s S&P BSE Sensex index reached a one-year high on Wednesday after climbing 8.9 percent this year.

“Lots of emerging markets are undergoing deleveraging,” said Standard Life’s Curtis, who helps manage $80 billion of fixed-income. “Russia is the most dramatic. The government has plenty of liquidity available form other sources and has made that liquidity available to help companies deleverage. Brazil too has been deleveraging.”

Not everything is rosy. South Africa’s markets are in turmoil amid reports Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan could face arrest as he battles with President Jacob Zuma over the management of state-owned companies. Mongolia is close to economic meltdown after commodity prices slumped and its spending got of hand.

In Venezuela, the opposition has called for a protest march on Thursday as it tries to push the government into holding a referendum to recall its wildly unpopular president this year. With stores empty, inflation in the triple digits and shortages of everything from staple foods to life-saving medicines, Venezuela is the most likely country in the world to default, according to credit-default swaps traders.

Yet in most of the developing world, companies are benefiting from a much-improved economic outlook.

Fueled by a combination of fiscal stimulus and monetary easing, China’s economy -- the second-largest in the world -- grew 6.94 percent in July, on track to reach its 6.5 percent target for 2016, according to the Bloomberg Monthly GDP tracking model.

Russia is forecast by analysts to exit its worst recession in two decades later this year as it benefits from the 21 percent surge in the price of oil in 2016.

Meanwhile, Brazilian President Michel Temer is helping restore investor and business confidence in Latin America’s biggest economy after two years of recession and political tumult. Analysts now expect Brazil to emerge from its deepest slump in more than a century next year, even after the second-quarter contraction was worse than forecast. Recent reports have shown that companies are optimistic about the future for the first time since 2014 and the high inflation that has plagued the country over the past few years is finally showing signs of slowing.

Temer became Brazil’s official president on Wednesday after senators voted to impeach Dilma Rousseff, a resolution to the political crisis that’s likely to be welcomed by investors.

“‘The EM story overall is still an attractive one because you still have positive relative growth,” said Yerlan Syzdykov, the head of emerging markets at Pioneer Investment Management in London. “In the next 12-18 months we will probably see growth picking up.”

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.