When the pace of events accelerates and perception travels faster than information, it’s sometimes difficult to keep up. Just a few days after we issued our expectation for interest rate cuts this spring, the U.S. Federal Reserve reduced its benchmarks by fifty basis points. It was the Fed’s first move of more than a quarter-point, and the first move outside of formal meetings, since 2008.

The urgency surrounding the decision was likely informed by the spread of the COVID-19 virus and the reaction of public health officials and the private sector. Restrictions on human movement and assembly have hindered production processes and taken a toll on service businesses around the world. With testing beginning in earnest in the United States, it seems likely that the number of reported cases will mount, as will the steps taken to contain the contagion.

It may be a few weeks before we see the accumulated business interruptions reflected in the normal flow of data, but the escalating number of anecdotes suggests upcoming economic announcements could be negative. That shortens the time frame for policy makers to react and reassure.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell promised on February 28 to “use our tools and act as appropriate to support the economy.” European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde said the bank was “ready to take appropriate and targeted measures.” Comparable statements from other central banks, and communication from G-7 finance ministers, clearly suggested a coordinated effort to combat the spreading malaise.

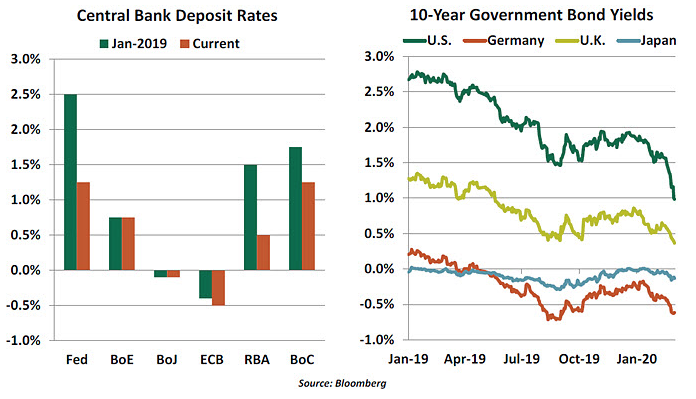

Unfortunately, central banks don’t have much room to reduce interest rates. Those that do have chosen to use it: the Fed, the Bank of Canada and the Reserve Bank of Australia have already moved, and the Bank of England will almost certainly act at (or before) their next meeting in late March. But other monetary authorities will have to rely on what we used to call unconventional policies, like quantitative easing or support programs for lending.

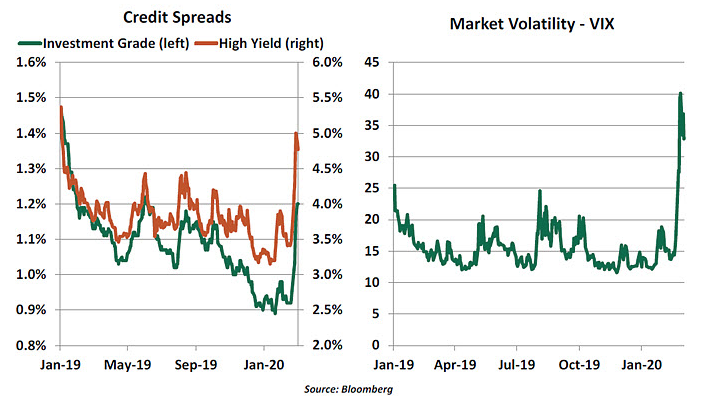

Given the size and timing of its action, the Fed was likely aiming to deliver a knockout blow to bearish sentiment. But the markets ducked and covered. The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield has fallen to below 1%, and equity markets remain unsettled. There is a possibility that market participants are interpreting the Fed’s urgency as a sign that conditions are worse than previously suspected.

Monetary policy may not be the best tool to address a pandemic. Lower rates will certainly not prevent the spread of the virus, ease the strain on global supply chains, or encourage travel in the face of corporate restrictions and personal anxiety. But central banks can address flagging psychology and tightening financial conditions: The reduction in interest rates might, at the margin, help some borrowers to avoid default. And as a side benefit, easier credit might help lift inflation.

But the more direct route to address both the virus and resultant economic dislocations is fiscal policy. Aid to support medical efforts, subsidies to protect impaired industries, and temporary tax reductions could all be considered. The U.K. is set to announce its formal budget plans next week, and they are expected to include meaningful support for the economy. But formulating and passing a stimulus package of sufficient size will face political complications; it might be a long time before new programs show meaningful effects.

Nonetheless, we expect the Fed to follow through with a further rate reduction this spring. For now, we’re slotting a second 50 basis point cut into the forecast. But the size and timing will depend critically on incoming information.

In the weeks ahead, we’ll be following the course of the coronavirus and its impact on markets and economic activity. But a handful of other things will also be worth monitoring:

-- Credit conditions. Companies that endure supply shocks may struggle through the middle of the year; companies (like those in the hospitality industry) facing demand shocks may struggle for longer. There is a mass of outstanding corporate debt that is just above investment grade; if the rating agencies become particularly bearish, the cliff effects that could result from downgrades within this community could cause dislocation in credit markets. Market-based credit spreads have widened importantly in the past few weeks.

Europe’s economy is heavily dependent on banks for credit. Banks in some countries are in reasonably good positions, while banks in other countries (like Italy) are challenged. Credit conservatism will rise regardless of geography, testing whether all of the countercyclical measures taken since the 2008 crisis will actually sustain the flow of capital in the economy during difficult times. Financial conditions in China also bear watching, as we noted a couple of weeks ago.

-- The stability of emerging markets. Many developing countries base their progress on commodity exports and inbound tourism. Both are under pressure; consequently, so are the currencies and capital markets in several places. International economic organizations are already dealing with a large caseload, and may not have the political or financial support that will be required if the current crisis does not calm soon.

-- The impact of low interest rates. The combination of flagging equity prices and falling interest rates will be challenging for pension plans and some financial institutions. Americans who have watched yields go negative in other markets may soon have to contemplate similar conditions.

Stress often reveals vulnerabilities that hadn’t previously been visible. COVID-19 is stretching the global economy; we’re hoping nothing breaks.

Something Rotten

“When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions” bemoaned Claudius in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.” Were he alive today, Claudius might see a battalion of economic challenges marching through Europe.

The COVID-19 outbreak is one more sorrow for Europe. The outbreak that originated in China has now established a foothold around the world. With more than 3,000 confirmed cases and 100 deaths, Italy is now home to one of the largest coronavirus outbreaks outside Asia. Meanwhile, other key engines of regional growth like Germany, France and the U.K. have seen a sudden spurt in cases.

After a decade of feeble economic growth, three years of messy Brexit negotiations (with more to follow), two years of U.S.-China trade tensions and looming threat of a tariff war with the U.S., a serious viral epidemic was the last thing Europe needed. Even before the outbreak, the continent’s major markets were barely growing, with Italy and Germany on the brink of recession. The virus may push them over the edge. The available data still shows little sign of impact, but the collapse of European equities is a sign that markets are pricing in a large hit.

Italy, the third-largest economy in the eurozone, is a particular concern. The country recorded its 17th consecutive monthly decline in manufacturing activity in February, even though the survey was completed before the outbreak intensified. Northern Italy, accounting for a little less than one-third of the nation’s economy, is currently under lockdown. Measures like these will only add to the woes of Italian manufacturers. Italy’s banks are among the weakest in Europe.

But even Germany, Europe’s largest economy, is facing a sizeable hit. The German automotive industry, already reeling under trade-related uncertainties, is bracing for further slump in demand and exports. According to a report from the Munich-based Institute for Economic Research, if the epidemic develops similarly to the SARS epidemic in 2003, a 1% slowdown in Chinese growth would reduce German growth by 0.06%. Given the virus’s fast spread within European borders, the actual impact will be far greater.

The impact to the U.K. economy, still the continent’s financial hub, was initially expected to be modest. But Brexit does not isolate the U.K. from a global downturn; the U.K.’s significant trade dependency on the EU and China, and slumping global equity prices, will weigh on its outlook.

Beyond supply-side disruptions in the manufacturing sector, domestic demand will also take a severe hit. The virus is affecting some of Europe’s most popular destinations. The tourism sector, accounting for 3.9% of Europe’s economy and nearly 12 million jobs, is suffering the most.

European banks carry high capital and liquidity buffers and are better equipped for a downturn now than they were during the 2010 sovereign debt crisis. But the higher defaults that would accompany a recession would force lenders to take losses. The region’s banks already have thin profit margins due to negative interest rates. While non-performing loans have fallen in recent years, they remain uncomfortably high in some regional economies.

Europe needs to use all appropriate tools and take concrete action to support growth and guard against downside risks. While the Bank of England (BoE) and the European Central Bank (ECB) stand “ready to take appropriate and targeted measures,” both are poorly armed for this battle. As discussed in the prior article, both have less room to cut interest rates than their U.S. counterpart does. And the ECB already deployed an asset purchase program last year. U.K. banks recently started issuing emergency loans to firms hit by the virus outbreak. More help from the fiscal side is desperately needed.

The Italian government has been quick to take this tack. It allocated €900 million worth of support measures, primarily targeting the north of the country. The package includes tax relief, a delay on utility bills and loan repayments, and a wage support scheme for firms temporarily cutting staff or working hours. The government then announced a second package worth €3.6 billion targeting affected sectors throughout the full country. Though significant, at about 0.3% Italy’s of gross domestic product, the measures are likely to fall short of keeping the country out of a downturn.

With these and additional support measures, Italy looks set to breach its deficit targets. The European Commission is lending support through its willingness to relax fiscal goals for Italy and others with large deficits. Emergency spending or lower revenues resulting from the outbreak will qualify for a waiver extended in the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact in 2015. Germany, meanwhile, has long honored its constitutional debt limit, resisting calls for fiscal stimulus. COVID-19 may finally force a shift toward accommodation. Germany’s finance ministry is looking to temporarily suspend the “debt brake” to help local government finances. The U.K. also has room to ease, and is set to announce a meaningful fiscal stimulus package in its formal budget next week.

The political consequences of economic woes are daunting. With nationalist parties gaining strength, disruption in major industries and labor markets could boost populist sentiment. And lost in the near-term focus on COVID-19 are negotiations on post-Brexit trade relations, which are not off to a strong start.

Battalions of euros and pounds will be needed to head off deepening economic sorrow in Europe. Policymakers are to be lauded for minimizing short-term disruptions created by the coronavirus, but the ultimate cure for the continent requires reforms and coordination that have proven elusive. Without the will to do what’s necessary, Europe will continue to face a sea of troubles.

Carl R. Tannenbaum is executive vice president and chief economist at Northern Trust. Ryan James Boyle is a vice president and senior economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. Vaibhav Tandon is an associate economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust.