When it comes to investing, Donald, Stephen and Brian Yacktman share a long family tradition. Donald, 78, pioneered a contrarian, deep-value style of investing that focused on unloved corners of the market. He founded Yacktman Asset Management in 1992 after a successful stint as a portfolio manager at Selected American Shares, and launched the Yacktman Fund soon after.

Stephen Yacktman, 49, started as an analyst at his father Donald’s firm in the early 1990s and began co-managing the flagship fund with Donald in the early 2000s. Today, Stephen is the fund’s manager and Yacktman Asset Management’s chief investment officer. Over the years, the $8 billion fund has undergone some changes, moving from its deep-value roots toward a more blended growth and value style mix. Its name was changed to AMG Yacktman Fund after Affiliated Managers Group (AMG) purchased a majority stake in the firm in 2012.

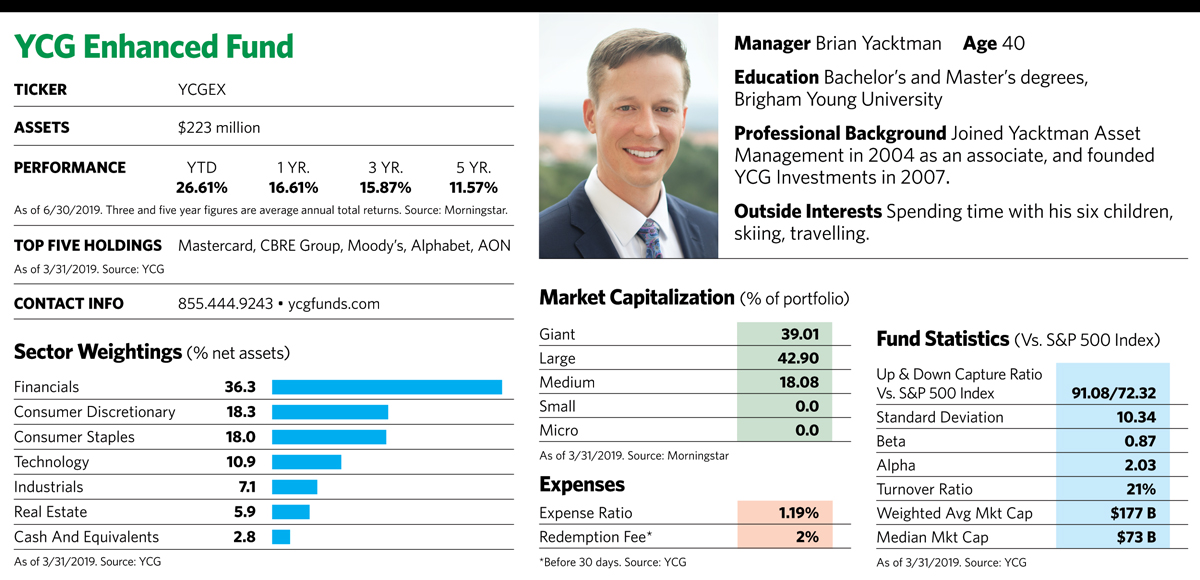

The latest Yacktman to make his mark on the mutual fund world is Donald’s 40-year-old son Brian, who founded YCG Investments in 2007 after working at his father’s firm for a few years. Today, YCG manages some $750 million, with about one-third of that attributable to the YCG Enhanced Fund and the rest to separately managed accounts requiring a $1 million investment minimum. The road to getting there was a long one, though.

When Brian Yacktman left his father’s firm to strike out on his own, he was expecting a friend to deliver $65 million in assets to manage. “But that didn’t come through,” Brian recalls. “The business got started with $1.5 million from a relative. And there really wasn’t a minimum account size because we were willing to take just about anything at that point.”

As part of the deal with AMG, Brian Yacktman cannot attach his family’s name to his business or mutual funds. But he’s keeping family under the firm umbrella nevertheless, and has brought on his brother Michael Yacktman, 32, who serves as senior analyst and lead trader.

Brian takes his firm’s early struggles in stride. In retrospect, starting his business just before the financial market crash in 2008 turned out to be more of a blessing than a curse. “We tend to shine in down markets,” he says. “It gave us an opportunity early on to prove ourselves.” By the firm’s 10th anniversary, YCG had nearly $500 million in assets under management.

He’s also sanguine about the restricted use of the family name. “Having a different name helps eliminate confusion in the marketplace,” he says. “And it shows we can stand on our own two feet.”

The YCG Enhanced Fund, which employs options strategies to reduce risk for its portfolio of around 30 stocks, has been doing that with finesse. It has ranked in the top 3% of performers in Morningstar’s large blend category for the year ending May 31, the top 2% over the last three years, and the top 3% over the last five years.

While Yacktman says he has taken in and appreciates many of the investment lessons his father taught him, the YCG Enhanced Fund goes its own way on a number of fronts. For one thing, the Yacktman Fund may have large chunks of money in cash when its managers think stocks are overvalued. At the end of March 2019, nearly 30% of its assets were there. By contrast, YCG has had less than 1% of its assets in cash for most of its nearly seven-year history. “As long as we can find investments at a price where we can expect an attractive return, we expect to be fully invested in most environments,” he says.

Conservative Options Strategy

The fund also distinguishes itself through its use of cash-secured put options on the buy side and covered call strategies for sales. Both strategies use no leverage and are designed as conservative trades to reduce risk and generate premium income. Yacktman says that in addition to that income, the strategy also offers tax advantages over simply holding the underlying securities.

A cash-secured put strategy is used by those who intend to own a stock at a target price lower than the current market price. In this strategy, the investor sells a put option to another investor but also has enough cash to cover the amount that would be needed to buy the stock if that put were exercised, or assigned, to the put seller. In a favorable outcome, the put seller/option writer keeps the premium he or she makes off the put sale and acquires the stock at the contract’s price. If the stock goes up, the writer keeps the cash from the put, which expires worthless. But if the underlying security falls to a price lower than the exercise price of the put option, the option will likely be exercised and the fund would be obligated to purchase the stock at more than its market value.

On the sale side, the managers may elect to sell covered call options against stocks already in the portfolio. If those stocks fail to rise to the strike price, the fund pockets the option premium and keeps the stock. The main risk here is when the stock soars past the strike price, forcing the fund to accept a lower-than-market price for the shares at exercise.

Although the fund has the word “enhanced” in its name to underscore its use of options, Yacktman says it has done so sparingly over the last few years because market volatility has been so low. At such times, option premiums are relatively paltry, and protective mechanisms such as covered calls and cash secured puts aren’t as necessary as they are when the market is more volatile.

“We’re not one of those funds that uses options on a certain percent of the portfolio all the time,” he says. “We only do so if it objectively makes sense.” In late June, there were cash-secured puts on only about 5% of the portfolio and there were no covered call positions.

Mining Human Behavior

As for stock holdings, Yacktman strongly believes that a repeatable investment strategy is grounded in taking advantage of behavioral tendencies. “The average investor’s get-rich-quick mentality and overconfidence in selecting the stocks they think will double quickly leads to two consistent types of mispricings,” he says. “The first is a consistent underpricing of high-quality, predictable stocks. The second is a tendency to overdiscount temporary macroeconomic and operational issues because investors are very short-term oriented.”

The fund focuses on the high-quality stocks of competitive global companies with strong, dominant franchises and the ability to raise prices under a variety of economic scenarios. These names must produce consistent cash flow and have the ability to remain robust under a variety of economic scenarios. He also likes to see high levels of executive stock ownership and conservative balance sheets.

Companies that fit the bill include luxury goods purveyors LVMH Moët Hennessy and Hermès International. “Humans are tribal and status-seeking, and people are always looking for ways to filter the appearance of value to the tribe. One of the best, most enduring ways to do this is to buy brands with global appeal.” Such brands retain their pricing power regardless of economic conditions, he says. Other leading consumer brands in the fund, including L’Oréal and the Estée Lauder Companies, hold similar appeal. “Personal care is one of the few industries accounting for a growing share of global GDP,” Yacktman says. “These stocks are recession-resistant.”

LVMH Moët, Hermès and L’Oréal are based outside the U.S., and among the foreign stocks representing about 17% of assets in the portfolio. Among the fund’s domestic companies, most of them earn more than half their revenues overseas. “We have found that the most superior risk-adjusted returns come from businesses possessing enduring pricing power and long-term volume growth opportunities,” Yacktman says, “and oftentimes, those attributes are to be found amongst businesses that are deeply entrenched in the global economy.”

Fund holding and tech giant Google is getting what he considers some unjustified backlash from investors concerned about the firm’s antitrust and regulatory challenges. He points out that the company’s global advertising revenues remain strong, and regulations could well throw up barriers to competitor entry into the space that would work to Google’s advantage.

In the financial category, the fund likes Charles Schwab, whose dominance in the marketplace makes it “the Amazon of the financial world, and an asset-gathering machine,” Yacktman says. Ratings service Moody’s also makes the cut as a company with staying power under a variety of economic scenarios. “Debt issuance has historically grown at least as fast as GDP, and capital market bond issuance has grown even faster as it has taken share from banking loans, Yacktman says. “Over the long term, we believe this growth is likely to continue.”

On the other hand, he avoids “hot” areas of the market, and initial public offerings fit that description right now. Like their forebears of the dot-com era, the vast majority of companies pursuing IPOs have yet to show profits. Since oil prices have fallen far behind the rate of inflation for many years, that scratches off energy stocks from Yacktman’s consideration as well.

Even companies with strong cash flows can be value traps if they aren’t prepared for change. Yacktman cites Pitney Bowes as an example. “Here’s a steady-eddy business with profitable economics that’s traded cheaply for over a decade, but is in a secular decline and produced awful returns for investors. Others that come to mind, such as IBM, GameStop, Hewlett-Packard, have all looked statistically cheap to free cash flows all the way down.”