Federal Reserve officials don't seem particularly concerned that stock valuations have plunged. They are, however, sensitive to significant movements in credit markets. The central bank would probably pull back on its plan to aggressively tighten monetary policy if corporate America showed signs of having trouble raising debt financing.

But despite some historic losses in credit markets this year, we're not anywhere close to that point. Corporate balance sheets are in some of the strongest positions in 20 years, and defaults are expected to stay “comfortably below” the long-term average of 4% this year, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts wrote in a note last week. Bank of America Corp. credit analyst Eric Yu concurs. "Even if we are headed into a recessionary scenario, we think that high-yield defaults will peak at under 6%,” he wrote in a research note last week. “We suggest taking materially more risk here."

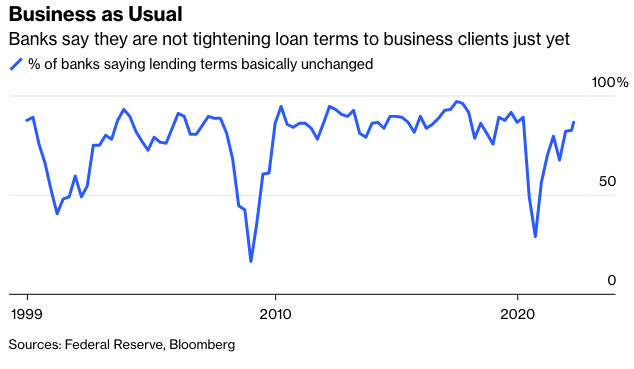

Even the Fed's quarterly senior loan officer survey of banks shows a willingness to lend. No banks reported significantly tightening lending standards in the latest survey, even with higher interest rates and concerns about higher inflation and a slowing economy. Lenders have confidence because companies aren’t desperate to borrow right now to stay afloat. They mostly took advantage of historically low rates to refinance a significant amount of their obligations, pushing out maturities years into the future.

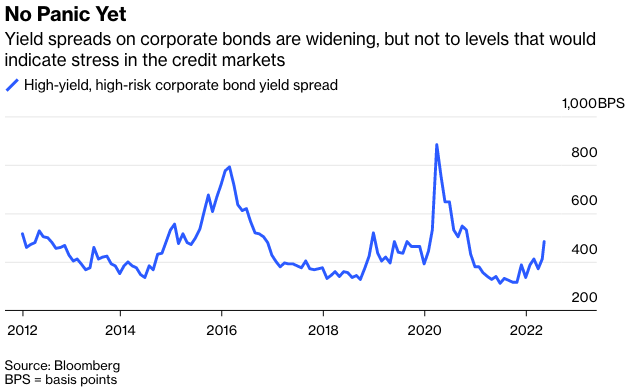

It's not like there hasn’t been any pain or cause for concern. US investment-grade bonds are down 13.4% this year, and high-yield, high-risk, or junk, bonds have fallen 10.4%, according to Bloomberg indexes. But the losses are mostly due to a broad repricing linked to higher rates on US Treasury securities rather than worries about deteriorating credit quality and potential defaults. Stripping out the government-debt component from the returns, junk bonds are up 0.7% and investment-grade bonds are down just 0.5%.

Normally, these signals would be supportive for equities and other riskier assets, since credit is a bellwether of corporate health and tends to lead other markets. But in this case, the mostly resilient credit market has become a liability for equity investors. It means that the bar is that much higher for the Fed to back down from its plans to aggressively raise interest rates and withdraw liquidity from the financial system by shrinking its almost $9 trillion balance sheet.

As is, stocks are getting buffeted by yields on inflation-adjusted Treasury rising above zero for the first time since before the start of the pandemic, making equities less valuable on a risk-adjusted basis. For example, the S&P 500 Index's dividend yield is near the lowest since May 2019 relative to real 10-year Treasury yields, which have climbed to 0.18% from as low as negative 1.08% in March.

Stocks are also getting slammed by the prospect of slower economic growth, higher costs for labor and raw commodities, and prolonged-supply chain disruptions. Some one-time havens, namely the US technology giants, have seen disproportionate declines in their share prices, with the Nasdaq Composite Index firmly in a bear market, dropping 26.5% from its high in November.

On the other hand, borrowers in the corporate bond market may have an easier time repaying their debts given the boost to nominal revenues and gross domestic product from inflation. Investors may be flipping to a period when credit provides a better hedge than equities to slower economic growth and faster inflation. After all, high-yield bonds actually provide the income so many investors have been clamoring for, offering average yields of 7.6%, near the highest since May 2020. Investment-grade bonds pay the most yield since March 2020, at 4.4%.

There is no credit crisis, and it would take an unforeseen event for it to become one anytime soon. Corporate bond investors are finally earning the income they've been craving for and they have little risk of not being paid in full and on time. This is positive for them, but for stock investors, the picture has shifted in the opposite direction. Without more pain in credit, equity markets can't count on the Fed to back away from its monetary-tightening plans simply to avoid further losses.

Lisa Abramowicz is a co-host of Bloomberg Surveillance on Bloomberg TV.