The Federal Reserve is taking a lot of heat over its handling of the highest U.S. inflation in four decades. Critics say that the central bank, which is expected to raise interest rates 75 basis points at its meeting on Wednesday, was too slow to recognize the problem and that it is still not doing enough to fight it. A close look at the record argues against that assessment.

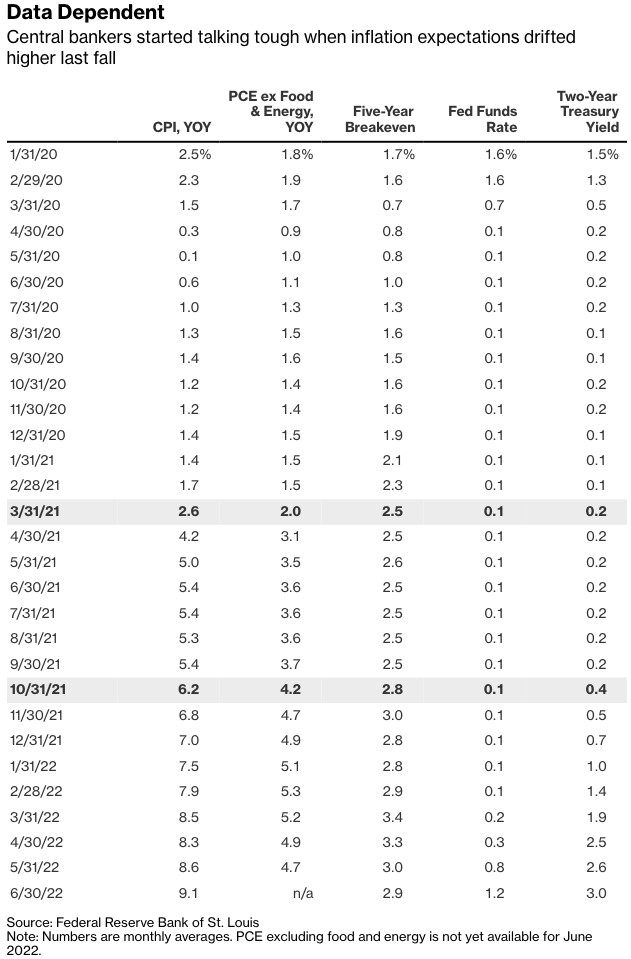

The following table lays out the record going back to the beginning of 2020. It shows year-over-year growth for the consumer price index, the best-known measure of inflation, alongside that of the personal consumption expenditures price index excluding food and energy, the Fed’s preferred inflation tracker. It also shows the five-year breakeven inflation rate, a widely used gauge of expected inflation over the next five years derived from the difference between the yield on plain vanilla and inflation-protected five-year Treasuries. And finally, it shows the federal funds rate, the Fed’s primary tool for fighting inflation, and the yield on two-year Treasuries.

First, and least controversially, I hope, it should be acknowledged that the Fed was right to intervene when Covid-19 shut down the U.S. economy in the spring of 2020. Year-over-year CPI hurtled toward zero and nearly tipped into deflation. The Fed rescue—aided by muscular fiscal stimulus—stabilized inflation, the economy and markets.

Despite record amounts of stimulus, the Fed struggled to raise inflation to its 2% target over the next year. That changed abruptly in March 2021 when CPI rose 2.6% over the prior year and PCE grew 2%. (I will focus on CPI rather than PCE because excluding food and energy overlooks much of the inflation people experience.) While I imagine the Fed was relieved to see inflation returning to more normal levels, it would have been hasty to declare victory based on a single month of data, so it made sense to wait to see whether March was an outlier or the start of a larger trend.

As it turned out, prices continued to rise through the spring of 2021, although it was not clear yet that higher inflation would linger. Historically, there have been many bursts of elevated inflation that lasted a few months and then receded. In addition, higher inflation readings were expected through the spring and early summer of 2021 because prices had been beaten down the previous year. Supply shortages and wild swings in consumer spending—not to mention that no one had ever attempted to shut down and restart the economy—also made it difficult to tell whether higher inflation had truly taken root. The market clearly didn’t think so because the five-year breakeven rate was moored at around 2.5% from March to September 2021, modestly above the Fed’s target.

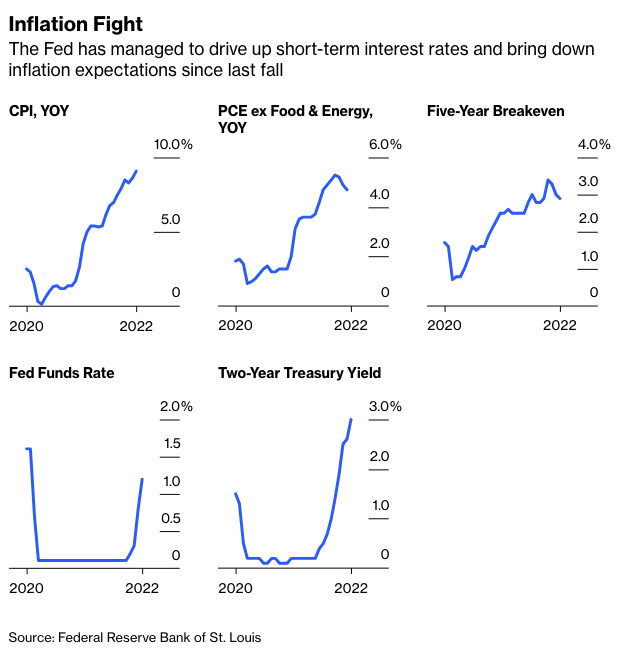

In October, inflation entered a new phase. Year-over-year CPI began climbing to more worrisome levels, and inflation expectations edged higher. Critics contend that the Fed sat on its hands at the time, but that’s a misreading of the record. While it’s true that the Fed waited several more months to raise the fed funds rate, it didn’t need to raise rates to have an immediate impact.

The fed funds rate is an overnight lending rate between banks, but its power resides in its ability to move short-term interest rates, which influence the entire economy. Central bankers began signaling their intention to fight inflation in the fall of 2021, causing short-term interest rates to move higher in anticipation. The two-year Treasury yield began to rise meaningfully in October 2021 for the first time in many years and has risen every month since. Eventually, the Fed had to raise the fed funds rate to maintain its credibility, which it began to do in March. Markets evidently find the Fed credible because the yield on two-year Treasuries is up to 3% from just 0.4% last October.

It's too soon to gauge the impact of the Fed’s efforts so far, although there are signs that inflation may be easing. My colleagues Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal cataloged a variety of prices that have declined, including industrial metals, shipping rates, used cars and lumber. Year-over-year PCE peaked in February and has declined every month since. The market is also signaling that inflation has topped. The five-year breakeven rate is back down to 2.6% from a peak of 3.6% in March.