The main act is almost upon us. There’s not much point in speculating at this late stage over exactly what the Federal Open Market Committee will announce at its Wednesday afternoon meeting. But if you’re concerned about investment, it’s hard to think about much else.

Here are some questions and concerns that the FOMC will need to ponder, as will the rest of us.

The Labor Market: It’s Still Hot

The slowdown in the latest gross domestic product numbers was greeted as evidence that higher bond yields were already having an effect. Less economic activity should, all else equal, mean less inflationary pressure.

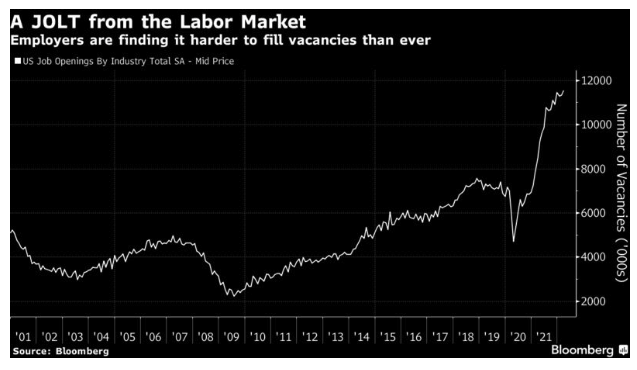

Unfortunately, the latest JOLTS numbers on job vacancies suggest there’s still ample upward pressure on prices (Source: Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics). There have never been more open jobs in the U.S. than there are now. Even with the economy plainly reopening from the pandemic, companies are still finding it hard to find anyone:

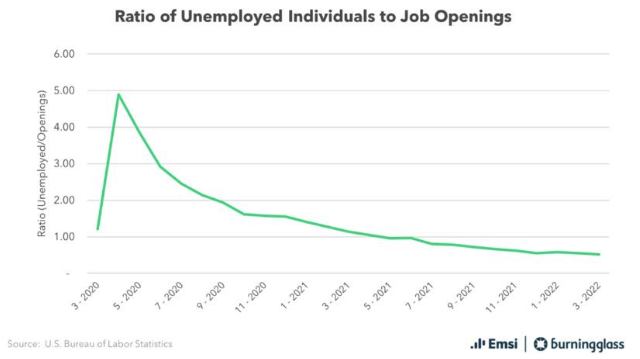

EMSI Burning Glass shows just how difficult it is for employers to keep wages low by illustrating the number of unemployed as a percentage of vacancies. Amazingly, each unemployed person has two jobs to choose from. If everyone signed on the dotted line tomorrow, there would still be approaching 6 million job vacancies:

Fed Chair Jerome Powell would be very unwise to follow his counterpart at the Bank of England and urge employees not to ask for a raise. That’s not the way the world works, and it’s not fair to expect of anyone. Any limits on an incipient wage-price spiral will have to come from deliberate policy to slow the economy.

New Dream Scenario: Soft Landing

Not long ago, there were real hopes of a return to Goldilocks—an economy that’s not too hot and not too cold. Now, the ideal outcome would be a Sully—an economy that somehow engineers a soft landing just as Captain Chesley Sullenberger once managed to ditch a passenger jet on the Hudson River. At present, the maneuvers to get the economy to slow down gently without tanking look as difficult and perilous as those undertaken by Captain Sullenberger as he tried to avoid crashing into Manhattan. But it could happen, and it would be great.

Perversely, however, the surprises of the last few months might just make it easier to execute such a landing. Dario Perkins of TS Lombard suggests that what’s been scary might actually be good news:

The odds of a policy error are increasing, especially when everyone seems to be over-extrapolating COVID distortions into a new secular inflation narrative and when central banks are channeling the virtues of Paul Volcker (or, in Europe, the ’70s Bundesbank). What we need is a “growth scare,” one that is sufficient to stop central banks freaking out but not large enough to plunge the world into recession. And with all parts of the world facing near-term problems, this scare is now a distinct possibility. Combine China’s property slump (and lockdowns) with a massive squeeze on real incomes in Europe, plus tighter financial conditions in the U.S., and perhaps the world economy will deteriorate just enough to put the authorities on a more cautious policy path. In fact, this “soft patch” may be our best chance right now of a “soft landing.”

It’s apt that we are now in the position of looking for help from disasters around the world. And it will be no small feat if the Fed can pull it off. The following chart from the foreign exchange team at Commerzbank NA defines a soft landing as an episode in which the the fed funds rate is raised without prompting a recession. Three-quarters of hiking campaigns end in one. The last soft landing came in 1994—and many would complain that the Alan Greenspan Fed on that occasion sparked a recession in Latin America and the rest of the emerging markets, even if one was avoided in the U.S.:

It’s just possible that the motley forces of Covid-zero, China Evergrande Group and Vladimir Putin could somehow allow the FOMC to bring the airliner of the U.S. and global economy safely to rest on the Hudson River. Not likely, but there’s a chance.

What Is A Real Rate, Anyway?

The Fed wants to tighten financial conditions, and that’s best measured by the real interest rate—the baseline rates that are payable after inflation. The problem: How do you measure those real rates, and are the markets judgments trustworthy?

There is a direct way to measure them in the economies that offer inflation-linked bonds. The problem is that those markets may not be efficient enough to trust. Dhaval Joshi of BCA Research puts it as follows:

Using the real yield on inflation-protected bonds as a gauge of the long-term real interest rate is possibly the biggest mistake in finance. The ultra-low real yield on inflation protected bonds captures nothing more than a stampede for inflation protection overwhelming a tiny supply of inflation-protected bonds.

Beyond that, Joshi also points out that the TIPS market tends to be swamped by the far bigger market for crude oil. Inflation-linked bonds tend to be used as a hedge by oil traders, which is a problem because this means that real yields tend to follow oil prices. As near-term rises in the oil price should all else equal reduce long-run inflation (by increasing the base), the relationship between the two should be inverse. In fact, they move together—when the oil price goes up so the price of TIPS rises compared to fixed income:

Joshi therefore suggests that the TIPS yield is best ignored. And there is evidence that it is indeed ignored. If the real rate really mattered more than the nominal rate for investments, and economic theory dictates that it should, then we should expect to see a stronger relationship between real rates and subsequent returns on stocks than between nominal rates and stocks. Experience over the last 15 years emphatically suggests that this is not the case.

Dec Mullarkey, managing director of SLC Management, offered these scatter plots showing the relationship between changes in different fixed income variables and changes in equities. The trend line for real rates is an almost perfectly straight line—in other words, there’s no relationship at all. There is a discernible relationship with nominal bond yields—as yields rise, so equities can be expected to rise. The strongest relationship is with inflation expectations, derived from the yields on TIPS. The more inflation expectations are rising, the better the returns for equities will be:

This suggests that we needn’t care too much about the fact that real yields have recently turned positive. It’s a faulty indicator.

But Mullarkey's exercise also implies to me that regime change is here, making all investment decisions harder. Since the Global Financial Crisis, if not before, we’ve been used to the idea that any increase in bond yields, or any increase in inflation expectations, is good because it means more activity in the economy, and less risk of a Japanified slump. Those assumptions are no longer operative. And that leads to another nasty consequence:

The Party at Club 60-40 Is Over

Much is riding on 60-40 funds; the jargon name for funds that mechanistically balance stocks and bonds. The classic allocation is 60% stocks and 40% bonds, which is how they got their name, even though many will tend to have a higher equity allocation than this. The most popular variant on the theme is the target-dated fund, which has become the investment management industry’s best attempt to replace the old-style defined-benefits pension, which few private sector companies want to offer. The idea is that savers are offered a fund with a target date for retirement, and asset allocation will be kept at appropriate levels according to how long there is until retirement. Younger people will automatically be given a higher weighting in equities. Each quarter there is a rebalancing to return to the favored asset allocation, which in effect means selling stocks and buying bonds after the stocks have risen. Over the last decade this has guaranteed continuing flows into bonds, despite their low yields.

How important are they? Recent research by the Investment Company Institute and Employee Benefits Research Institute shows that such funds have become the backbone for retirement saving in the U.S. Much is riding on them:

Automatic asset allocation has been particularly useful in persuading younger people to sign up to pensions. In many ways, this replaces the old paternalistic model of defined-benefit plans, gently guiding people into sensible allocations:

The problem is that this is predicated on the notion that they will not fall at the same time. As shown in Mullarkey’s charts, we’ve become accustomed to the idea that as bond yields rise (and their price falls), so stocks will rise, and vice versa. But in this environment, it looks as though we should get ready for that relationship to change, which could shake confidence in retirement saving as it is currently practiced.

Here are the monthly returns on Bloomberg’s index of U.S. 60-40 investments, going back to 2007. Only the disaster months of October 2008 and March 2020 were worse than April of this year:

It gets worse. There is also a marked relationship between the Fed’s addition or removal of liquidity and the success or failure of 60-40 funds, as shown in this chart from MUFG Americas:

When the Fed is priming the pump with quantitative-easing asset purchases, 60-40 does well, and when it attempts to tighten with QT, 60-40 plans do badly. We learn today about what the Fed will do about quantitative tightening, and it’s likely to put even more pressure on retirement plans.

The irony is that higher bond yields have actually made life easier for defined-benefit plans, because they make the liabilities they have to guarantee cheaper. For people saving in target-date funds, any continued pattern of falling bonds and equities is going to look terrible, and could shake a generation’s faith in their retirement savings. It’s one of many risks with which the FOMC must contend.

Survival Tips

It’s always a good tip to remind everyone to treat people with kindness. The New York Yankees are in the middle of an epic winning streak at present, which I’m not enjoying, but an incident from their win over the Toronto Blue Jays tonight warmed the heart. The Yankees’ star Aaron Judge hit a home run high into the stands, a Blue Jay fan retrieved it—and then immediately gave it to a young boy wearing an Aaron Judge shirt in the row behind him. The boy was consumed by emotion. It’s a wonderful gesture that he’ll remember the rest of his life, and I imagine the good Torontonian will feel far better for this act of generosity than he would had he simply held on to the ball as a souvenir.

Another tip is to remember that Canadians really are that nice. Even at sports games. The one time I went to see the Blue Jays in Toronto, they lost a very exciting game to the Red Sox with David Ortiz slugging the game-winning home run (on what proved to be the last time I ever saw him at bat before his retirement). Exquisitely, Ortiz even did this off Joaquin Benoit, the pitcher he had victimized three years earlier in one of the most dramatic moments of his career. Sitting with a Red Sox cap surrounded by people in Blue Jays blue was not remotely uncomfortable. And when the boy behind me yelled “Boston sucks,” his mother insisted that he apologize to me. Such niceness and courtesy does make for a happier life, and it doesn’t have to stay in Canada. So, be nice to people—and if you need guidance on how to do this, maybe go to Toronto.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.