Covid-19 is truly the mother of all crises, and no economy in the world has been spared. While some are returning to growth, many are finding it extremely difficult to engineer a recovery. Advanced economies had the fiscal space to support themselves by accruing large sums of debt, but many developing economies lack sufficient financial resources to improve public and economic health. Entire nations are finding themselves on the downward leg of the K-shaped recovery, and may require forbearance from their creditors.

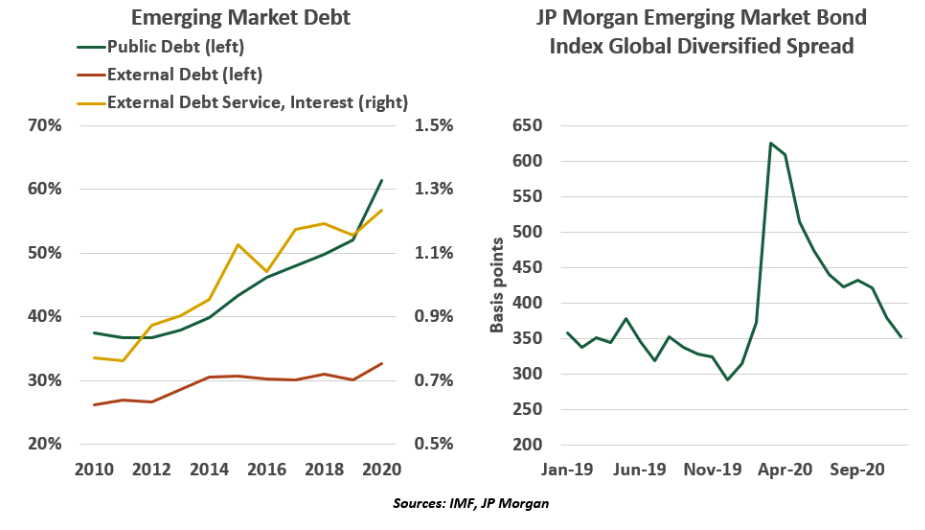

The pandemic is pushing an increasing number of developing countries into debt distress. Many of them were already experiencing what is known as a debt super-cycle, in which the interest on accumulated debt reaches to a point where it becomes difficult to service. For some countries, a crisis looks imminent, while for others the day of reckoning has been delayed by the exceptionally low global interest rate environment.

The past decade has witnessed the largest and fastest debt buildup ever seen in emerging markets (EMs). Although China accounts for a significant part of this increase, debt buildup has been broad-based across EMs. Fortunately for now, investor appetite for EM debt has been rising, pushing yields down noticeably.

With trade, tourism, remittances and investment flows disrupted by the pandemic, many EMs have seen a drastic decline in their foreign exchange incomes, which makes it harder to service their debt obligations. Problems are seen across regions; some nations find themselves back in trouble after a long history of defaults.

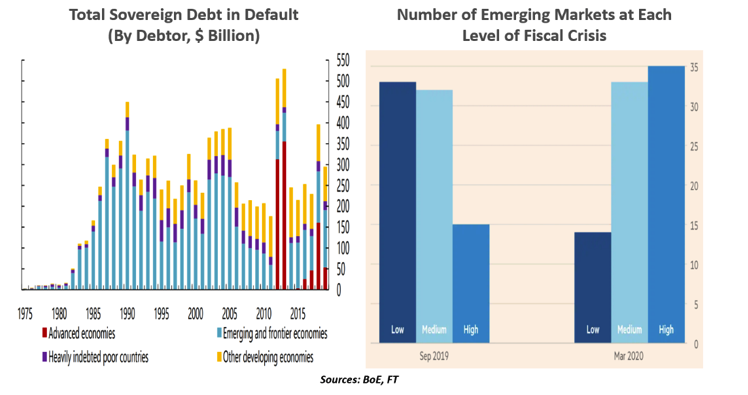

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, developing economies are facing repayments of between $2.6 trillion and $3.4 trillion on their public external debt in 2020 and 2021. Default risk is rising, and so is the call for debt relief. EMs will require support in the form of grants, concessional financing or debt restructuring.

Multilateral institutions like the Paris Club have been working on providing relief. The Paris Club is an informal group of creditor countries (usually represented by officials from Treasury Departments) focused on designing coordinated and sustainable debt relief to debtor nations. Its workload now includes 471 agreements with 99 debtor countries covering $589 billion.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is another important agent in this area. The IMF has pools of funding amassed from its members that can be used for debt restructuring: the Fund has lent $105 billion to 85 nations since March 2020 and cancelled repayments from the weakest economies. The World Bank has set aside $160 billion to lend over the next 15 months, with an additional $80 billion allocated by other development banks. These efforts, while helpful, will likely fall short of the ultimate need.

The sovereign debt restructuring process can be protracted and difficult. It involves substantial bargaining in which the debtor agrees to higher future debt in exchange for lower payments now, deferring but not eliminating default risk. As a result, a number of restructurings involve litigation by bondholders seeking to extract a preferential recovery. On average, it takes about seven years to resolve the most difficult situations, and the process typically involves multiple steps.

Several developing economies have been taking on debt on less concessional terms from private lenders and non-Paris Club members. Defaults involving the Paris Club of official creditors are declining while those involving bilateral creditors, including China, have been growing.

This presents a challenge. China, which is not a member of the Paris Club, has emerged as a source of more financing for poor countries than all other creditor nations combined. Some wonder whether China’s intentions are altogether benign; loans granted under China’s Belt and Road Initiative have been criticized in some corners as predatory, with the ultimate objective of gaining control over ports or commodities.

But China has stepped in because Western nations have failed to provide synchronized relief to poorer economies. The recent tone from the U.S. has not been positive towards these resolutions, but President Biden has indicated his willingness to work with global institutions on this front. One angle being promoted by Washington is providing “green debt relief” to developing countries ready to make climate commitments.

The U.S. stance opposing additional allocation of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) could also change. SDRs are supplementary foreign reserve assets allocated in line with nations’ share of the world economy, which would help provide much-needed liquidity to countries with tight public finances.

All Stakeholders Must Cooperate To Find A Sustainable Solution To Unsustainable EM Debt.

Developing countries are already suffering from the damage to public health caused by Covid-19. A debt crisis on top of that would be catastrophic and could trigger unrest and political instability. Historical episodes, like the 1997 Asian financial crisis, show that a debt crisis even in a small nation can spiral into a significant event around the world, leading to losses for financial institutions and potential instability within financial systems. Hence, strong multilateral cooperation will have benefits beyond the financially vulnerable nations receiving aid.

Covid-19 might be the mother of all crises, but in times like these, necessity can be the mother of invention. With that thought in mind, we are hoping that developing countries and the organizations that represent them will come together to provide a sustainable, durable solution to the debt burden of developing economies. It isn’t a matter of throwing good money after bad; it’s an investment aimed at avoiding damaging long-term economic and social damage from this once-in-a-century calamity.

Green Shoots

In December, the Federal Reserve announced it had joined the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). The Fed was one of the last major central banks to become part of NGFS, which now has 83 members.

While banking is not known to be a polluting or energy-intensive industry, the risks associated with climate change are requiring more attention from financial companies. As an example, increasingly frequent bouts of severe weather, caused by warming air and seas, can threaten waterfront properties and loans secured by them. Some borrowers in high-emission industries may face new regulations that could impact their ability to repay loans. Climate extremes may eventually make commerce almost impossible to conduct in some places, placing regional lenders in peril.

Central banks are not prescriptive as to which loans banks should fund or decline, but they do have a vested interest in ensuring the health of the financial sector. Nearly all central banks’ remits include a mention of stability. Some, like the Federal Reserve, have a narrow scope of price stability (or managing inflation), while others have a broader mandate of supporting sustainability or furthering domestic agendas. As a changing climate may reduce stability in many respects, central banks must consider how the financial sector is preparing for this possibility.

NGFS is an international working group for central banks to cooperate in addressing the challenges of climate change. Its work is organized into five streams:

• Microprudential / supervision guides practices for integrating climate risks into bank regulation.

• Macrofinancial develops climate scenarios for bank stress tests and provides guidance on integrating climate risk analysis into banks’ regulatory reporting.

• Scaling up green finance promotes the adoption of sustainable principles in central banks’ investments.

• Bridging data gaps and Research coordinate data and research publications across NGFS workstreams.

Climate Change Is Too Large A Risk For Banks To Ignore.

NGFS membership is voluntary, and its role is only advisory. NGFS members can share and build on each other’s experiences to find better ways to address the consequences of climate change.

Thus far, the Bank of England (BoE) leads the world in this arena. It was among the first to require its member banks to perform climate stress tests. After postponing the planned launch in 2020 due to the pandemic, this year’s tests will include climate risks for the first time. Bodies like NGFS will build on these exercises to develop best practices for climate stress testing.

The role of central banks in climate matters does merit some discussion. Some of it is political, as evidenced by the 47 lawmakers who petitioned Fed Chair Jerome Powell to avoid climate stress tests and stay out of NGFS. Some skepticism is principled: Why should climate risk be in the scope of bank stress testing, but not other global risks like pandemics or trade relations? Why use monetary policy to nudge investments when direct measures like carbon taxes are more effective? But the financial industry is clearly moving toward consensus that climate is an appropriate consideration in financial regulation.

One of the upside stories of 2020 was the resilience of the financial sector during the stress of Covid-19 shutdowns. Risk management practices established after the Global Financial Crisis left the industry ready for that idiosyncratic event. Preparing for the foreseeable risk of climate change will similarly help keep the financial sector working well, and generate some green in the process.

Lacking Currency

The presentation was going very well. Questions related to the pandemic, the Biden economic program, and U.S./China relations had all been handled adroitly. But then, someone asked about bitcoin. Maintaining poise was difficult from that point on.

Cryptocurrency curiosity peaked in early 2018, when one bitcoin was worth more than $20,000. By the end of that year, bitcoin had lost 75% of its value and the volume of inquiries we fielded about it dropped commensurately. Things remained fairly quiet until last fall, when the price of a bitcoin began an ascent that crested recently at more than $40,000. And the questions returned.

Our answers on the topic have not changed over the past three years. We share them here, in the hope that we can move on from bitcoin questions once and for all. We are skeptical about the current collection of cryptocurrencies, and here’s why:

• The values of the leading virtual currencies are very volatile. To be fair, the values of the dollar, euro and yen fluctuate every day in the foreign exchange markets, but not nearly to the same degree. The purchasing power of the top cryptocurrencies is highly uncertain, making them poor mediums of exchange.

• There is no clear ownership or control of the supply of cryptocurrencies, which leaves them vulnerable to debasement. Further, cybertheft is not uncommon; bitcoin wallets have been hacked frequently.

The Technology Used By Bitcoin Has Promise, But The Currency Is Of Dubious Value

• Bitcoin transactions are anonymous, making them ideal for illicit activity like ransomware. International law enforcement is working toward curtailing this channel.

• The penetration of e-commerce has diminished the need for currency of any kind. Frictions in transacting are dropping naturally, diminishing the need for cryptocurrencies.

• Bitcoin is one of more than 5,000 cryptocurrencies. Competition is keen, making it hard for individual products to establish primacy. And central banks may one day enter the fray with products whose credibility will give them an immediate advantage.

• There is no evidence that cryptocurrencies serve as a hedge against inflation.

The blockchain technology that underlies cryptocurrencies is of substantial value, and is already being applied productively to transactions in goods and securities. But to us, bitcoin and its brethren are of very questionable value.

Carl R. Tannenbaum is executive vice president and chief economist at Northern Trust. Ryan James Boyle is vice president and senior economist at Northern Trust. Vaibhav Tandon is second vice president and an economist Northern Trust.