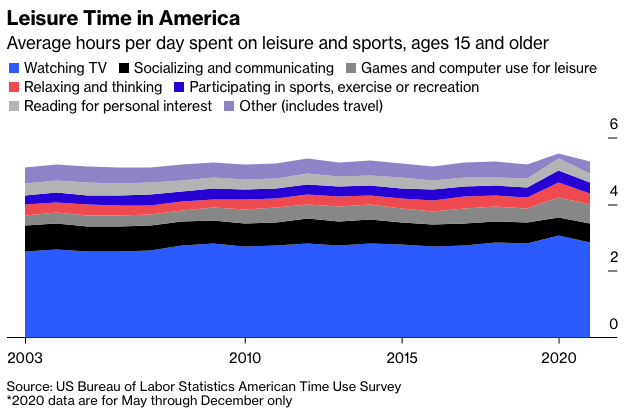

Along with some less-welcome changes, the Covid-19 pandemic brought many Americans a respite from time pressures. Average time spent sleeping went up by about 10 minutes a day in 2020, and time devoted to leisure and sports activities went up by about 32 minutes, according to the American Time Use Survey conducted by the Census Bureau on behalf of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Recently released data for 2021 show an apparent reversion toward (though not all the way) to pre-pandemic norms:

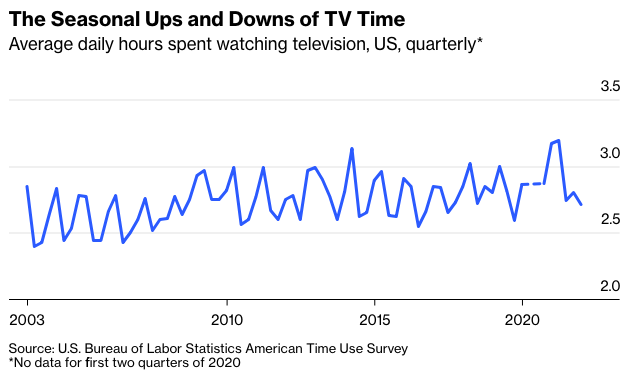

There are some comparability issues here because the 2020 survey was interrupted by the onset of the pandemic. There are seasonal differences in leisure activity and the BLS ended up publishing only the results from May through December. But they’re not big issues: The 2019-2020 comparisons in the first paragraph are based on May-December data from both years, and quarterly numbers available for TV-watching time show a big winter 2020-2021 peak and then a falloff that actually left TV time lower in the fourth quarter of 2021 than in any fourth quarter since 2007—a shift that has left its mark on the stock prices of Netflix Inc., Walt Disney Co. and others.

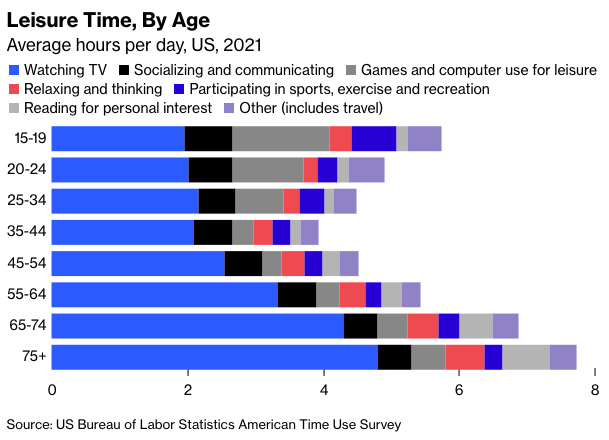

A more serious problem with these time-series statistics, in particular the modest uptrend in leisure time they were showing even before the pandemic, is that the U.S. population keeps getting older. Old people have a lot more leisure time than everybody else, which could be driving the rise in overall leisure time.

Sure enough, if you separate things out by age group it’s not clear that there has been any increase in leisure time since the first time-use survey in 2003. Of the smaller assortment of age groups for which the BLS offers historical data, half (those 25-34, 55-64 and 65 and older) have seen an increase in leisure time since then and half (15-24, 35-44 and 45-54) a decrease. Most of the changes have been so small that they could just be sampling error, which is why I’m not bothering with a chart. This is not the case, though, for the group that has seen the biggest decline in leisure time since 2003, and had the least to begin with.

I speak here of my fellow Americans ages 35 through 44, who are often parents of young children and at pivotal, high-stress stages in their careers. I was among this group in 2003 and remember feeling overwhelmed pretty much constantly. It gets better, I swear: Measures of subjective well-being indicate that, in the U.S. and many other countries, it bottoms out when people are in their mid- to late-40s and then begins a long rise.

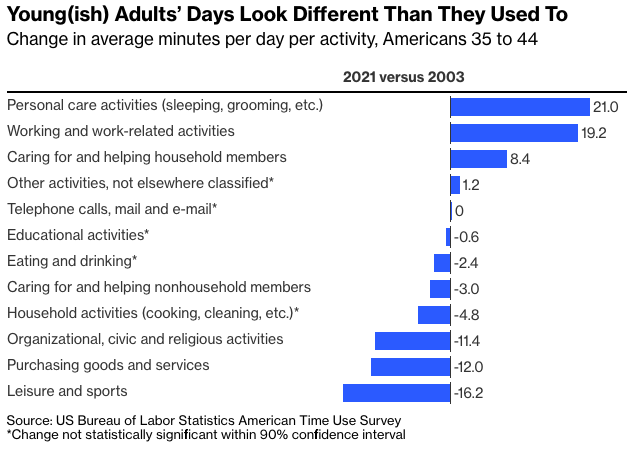

In the meantime, though, the time pressures on Americans 35 to 44 seem to keep getting worse. They have lost more than 16 minutes in average daily leisure time since 2003, with the pandemic providing no real respite.

Where did that lost leisure time go? To work, sleep and child care, mainly. Here’s what has happened since 2003 with the 12 umbrella categories into which the BLS divides time use (the numbers should thus add up to zero, but don’t quite because of rounding).

The increase in time devoted to personal care sounds like a positive development, but there are caveats. It’s mostly increased sleeping time, which in the survey’s accounting includes “spells of sleeplessness,” and has been boosted since 2019 by a 4.8-minute increase in “health-related self care” that is clearly due to the pandemic and isn’t a positive development at all.

As for time devoted to work, it includes work-related travel time—mostly commuting—which fell 5.4 minutes from 2019 to 2021 thanks to the pandemic-induced shift to remote work. This means 35-to-44-year-olds’ non-travel-related work time is up nearly 25 minutes since 2003. Meanwhile, the increase in time spent caring for and helping household members was entirely about the kids, who took up 11.4 minutes a day more in 2021 than in 2003 while time spent caring for other household members fell.

On the other side of the time balance sheet there were 12 fewer minutes a day devoted to purchasing goods and services, surely a byproduct of the rise of e-commerce. This effect is apparent across all age groups, although the 35-44 group was tied with 55-64 for the biggest time savings. The decline in time spent on organizational, civic and religious activities, which doesn’t seem like such a great development, is apparent and statistically significant across all age groups except those 65 and older, but is biggest by far among the 35-44 group.

Then there’s leisure time, where this all started. Sixteen lost minutes may not sound like much, but that’s a daily average that works out to 98.6 hours a year. Multiply that times the estimated 43.4 million Americans in the age group as of mid-2021 and you get almost 4.3 billion lost leisure hours last year. Which sounds like a lot.

As is apparent if you eyeball the chart showing the age group’s leisure time through the years, the losses have come mainly since 2012. What could have caused this? My guess is that it’s been an after-effect of the nation’s economic woes during and immediately after the Great Recession, when most of those now aged 35 to 44 were in their 20s and just getting started on adult life. Trying to get started, that is: The terrible job market forced many to go back to school, move back in with their parents and/or delay buying homes and starting families. They’ve been playing catch-up ever since, which has wrought a certain amount of havoc with their daily routines.

On the positive side, this could portend a leisure-time recovery for future 35-to-44-year-olds who didn’t face such economic crosswinds in their 20s. For now, though, it means that those in that age group really are especially pressed for time. So be kind to your local 35-to-44-year-olds. Maybe even offer to babysit.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. A former editorial director of Harvard Business Review, he has written for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is author of The Myth of the Rational Market.