Many financial professionals still recite a pat response when clients ask about socially responsible investments: Beware! They will likely underperform the broad market.

A decade ago, that answer was fairly accurate as a generalization. Take, for example, the so-called “sin” stocks, such as alcohol, tobacco and gaming. A 2007 Journal of Financial Economics paper called “The Price of Sin: The Effects of Social Norms on Markets,” found that these stocks outperformed peers (returning about 3% more per year). Since most socially responsible investing at the time purposely excluded these stocks, they could be expected to underperform.

Today, the underperformance argument sounds fairly uninformed. Socially responsible investors at the time were largely foundations and endowments. Their aim wasn’t to earn a higher rate of return; it was to avoid supporting undesirable activities, arguably even to punish the enterprises that participated in them. And by appearances, it worked.

A key principle of investing is that as the price of a stock goes down, the expected return goes up. This is governed by a simple equation known as the “dividend discount model.” Simply put, the stock price is equal to the future dividends (or cash flows) it pays, divided by the required rate of return. (A growth rate is also subtracted from return.)

Stock price = Dividends / Expected return

The return the investor expects to earn is, in fact, the equity cost of capital for that stock. By pushing the prices of these stocks down, institutional investors drove their expected return up. The expected return to investors is the cost those firms have to pay to access capital from the market. Mission accomplished.

Now let’s take environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing today. A variety of themes spring from these three buckets, and they’re much broader and more far-reaching than the original premise for socially responsible investing. Environmental investments, for example, may look to underweight or eliminate polluting companies or high carbon emitters, while socially directed investments might rank firms on working conditions and employee relations or human rights records. The governance approach considers issues such as the diversity of a company’s board, corruption and accounting aggressiveness.

Many ESG investors feel that it’s good enough just to support companies working toward a better shared future. Indeed, how much money can we all make in the long run if we let the world go to pot? As Mark Carney, a former governor of the Bank of England and a strong ESG proponent, noted recently on Twitter, “We’ve been trading off the planet against profit for too long. This has depleted our natural capital, had devastating effects on Earth’s biodiversity and is causing unprecedented changes to our climate.”

The large companies that essentially own everything have long understood how systemic problems are investment problems. But how do these problems affect an individual investor’s returns?

Though ESG has evolved from its origins in socially responsible investing, in one sense the story is the same. Just as investors avoid tobacco and drive its price down and return up, investors could conceivably drive up the price of renewable energy firms or companies that invest in their workers, and the expected returns for these “good” companies would then possibly decrease, right?

That’s true by itself, but ESG also offers something else: an “alpha thesis.” There are good reasons to believe that investor preferences for these stocks will be validated by better actual corporate performance that leads to higher cash flows. Thus, the numerator in the dividend discount model would go up, offsetting the denominator increase that reflects increased investor interest.

Why might ESG-aware firms outperform? There are a variety of specific reasons that have been given—that these companies avoid fines and can respond better to physical threats and cost efficiencies. But an even better answer is that these companies are the ones prepared to operate in a changing landscape. Climate change can irreversibly alter productive operations as we know them. And clients, regulators and business partners are increasingly demanding that the private sector incorporate ESG concerns into their businesses. As with any paradigm shift, there will be winners and losers, and investors are looking at ways to make sure they are investing in the winners.

Thus, for many people, ESG investing is not just about incorporating their values in their investments, but also about adding value—reducing risk, adding return or both.

The impact of climate change in particular is a risk that many in our industry are sounding alarms about. Larry Fink, the CEO of the world’s largest money manager, BlackRock, took an unmistakable stance in his 2021 letter to CEOs: “There is no company whose business model won’t be profoundly affected by the transition to a net zero economy—one that emits no more carbon dioxide than it removes from the atmosphere by 2050, the scientifically established threshold necessary to keep global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius. … Companies that are not quickly preparing themselves will see their businesses and valuations suffer, as these same stakeholders lose confidence that those companies can adapt their business models to the dramatic changes that are coming.”

BlackRock is not alone in this thinking. European policy makers have arguably led the march to incorporate rules about climate, but the United States is quickly following suit. The Biden administration has made climate risk and ESG top priorities, not just in social arenas but in financial ones. For example, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has pledged to put together a team to look at financial system risks arising from climate change, which she refers to as an “existential threat.”

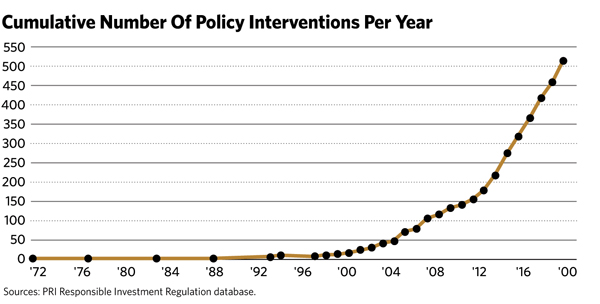

The Principles for Responsible Investment, an international network of investors working to understand and incorporate ESG, tracks regulations pushing investors to consider long-term value drivers such as the sustainability of an investment. Its 2019 update showcases the tremendous increase in the number of policy interventions. (See the graph.)

Investors seem to be listening. Interest in ESG investing has increased dramatically over the last several years, and it’s not just the purview of pensions and endowments anymore.

Sustainable funds pulled in $51.1 billion in net flows in 2020, more than doubling the record set the year before, according to Morningstar’s 2020 “Sustainable Funds U.S. Landscape Report.” Fund flows into these products accounted for nearly one-fourth of overall flows into funds in the United States.

So what should people now expect from the performance of environmental, social and governance investments? Thousands of studies have tried to answer this question. But the truth is that, for the individual advisor or investor putting together a portfolio, there is no correct sweeping answer, particularly since these investments can vary dramatically. More sophisticated approaches—oftentimes not just excluding unwanted companies but more carefully integrating ESG themes to under- and overweight within sectors—can minimize tracking error, making it possible to invest in ESG without betting the farm. There are also thematic investments for certain trends—bets on companies poised to manage well in, say, an age of water scarcity or that will benefit from diversity in their management teams.

The track record on these newer investments is just not long enough to be able to judge empirically. The early evidence is positive, though: ESG funds performed particularly well in 2020 and showed they could reduce investors’ risk. A 2015 meta study conducted by researchers from Deutsche Asset & Wealth Management, the University of Hamburg and the University of Reading, combined the results of about 2,200 studies on ESG and corporate financial performance going back to the 1970s. About 90% showed that ESG didn’t have a negative effect on performance, and the majority of the studies found there was a positive relationship between ESG and performance. Portfolio studies were less positive, however, suggesting that investors using vehicles like mutual funds had not necessarily seen this outperformance.

In a more recent meta study, the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business and Rockefeller Asset Management looked at 1,000 papers on ESG done in the last five years. Among the findings was that sustainability initiatives appear to lead to improved risk management and greater innovation.

Governance themes in particular seem associated with positive return and reduced risk. In 2019, MSCI published its own study and found “significant evidence that the application of MSCI ESG Ratings may have helped reduce systematic and stock-specific tail risks in investment portfolios.” MSCI has also begun looking at ESG as its own factor, and early evidence is that its efficacy in explaining stock-specific risk is increasing, possibly because of increased firm investment in sustainability-related measures.

Is recent outperformance the reason money is piling into these investments? Maybe. There’s a shorter-term aspect to the alpha thesis that might also be driving such interest—namely, the desire among investors to simply ride a wave up. Many investors believe that at some point there really is no ESG investing, since such quality considerations would simply become incorporated into people’s analysis the same way other risk considerations are.

In the meantime, as investor preferences for these stocks drive their prices up, investor returns will likely be positive as prices rise to a new equilibrium. So maybe all we have to believe today is that interest in ESG will continue to increase.

Dana D’Auria, CFA, is co-chief investment officer at Envestnet.