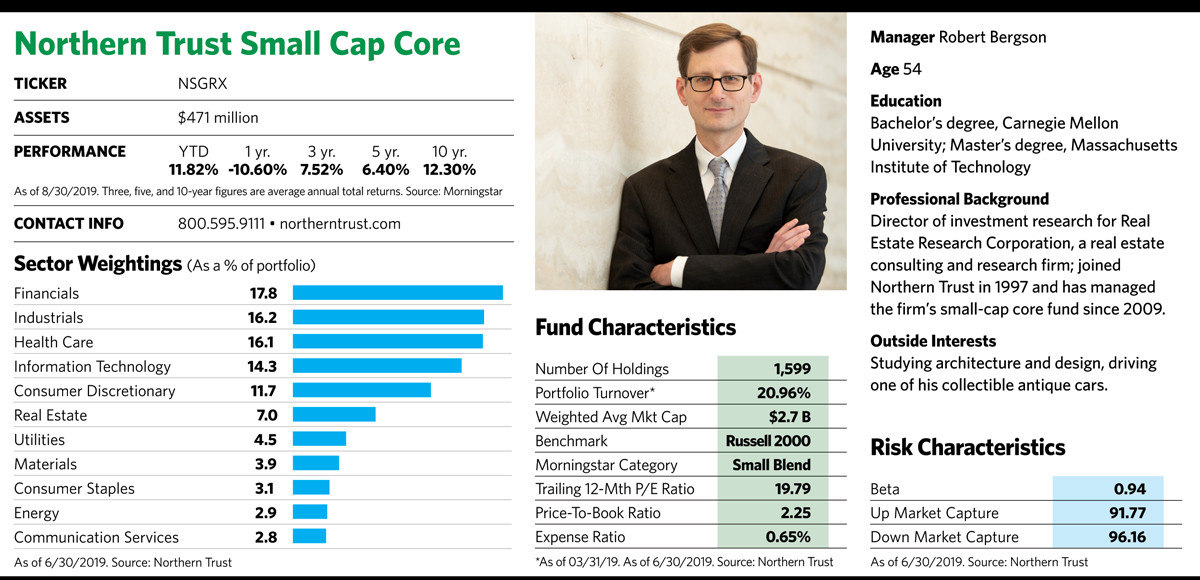

Robert Bergson admits that the fund he manages, the Northern Trust Small Cap Core Fund, isn’t likely to surge to the top of the performance charts for any given year. To the veteran manager, who has run small-cap portfolios since 1999, that’s really not the point anyway.

“We look to produce above-benchmark returns over the long term without increasing risk,” he says. “In the process, we’re likely to hit more singles and doubles than home runs.”

Bergson aims to achieve that modest goal using a strategy based on factor investing, a focus of new product introductions in the ETF world, but a strategy that has a much smaller following among mutual funds. In contrast to fundamental valuation techniques, which look at company-specific characteristics such as earnings or cash flow, this fund and others offered by Northern Trust focus on “factors” that tend to drive risk and return. These include a stock’s value, price momentum, volatility, size and quality.

Tricky Business

Proponents of factor investing point to academic research suggesting that using the factors can generate higher risk-adjusted returns than the market. But applying factor-based methodology successfully has proved to be a tricky business for even the most sophisticated investors. A recent study of 500 institutional portfolios by Michael Hunstad, head of quantitative research at Northern Trust Asset Management, found that most were using factors in a less than optimal manner and getting disappointing investment results. Some combined factor-based portfolios with other investment management strategies, which muted the benefits of factor investing. Others fell short because they failed to combine factors in their portfolios effectively.

Putting together a multifactor portfolio, as this fund does, is kind of like cooking. A recipe using good ingredients in the right proportion yields a tasty dish, while the wrong mix results in a bland concoction. Similarly, the success or failure of multifactor ETFs and mutual funds rests on the components they use and how they’re put together.

In this fund, which relies almost exclusively on quantitative analysis, Bergson and his team try to avoid both stocks that could become value traps as well as those exhibiting signs of unsustainable growth. To do that, they toss out what their models consider the lowest quality stocks in their benchmark, the Russell 2000 Index, and keep the better ones in. Companies can show signs of potential underperformance by suffering declining profit margins or weakening cash flow or by demonstrating an excessive need to tap capital markets for growth rather than to achieve it organically. A momentum factor means that stocks whose prices have been floundering for a while also land on the low-quality list and are ripe for a sale.

The methodology is designed to weed out the losers rather than pinpoint the winners. “Low quality stocks tend to underperform over the long term,” Bergson says. “At the same time, it’s easier to identify characteristics of small companies that are likely to underperform than those that are likely to outperform.”

The fund looks similar in some respects to the Russell 2000. It spreads its bets widely among 1,599 holdings, just shy of the 1,976 index names. It has a similar trailing 12-month price-to-earnings ratio, as well as a nearly matched price-to-book ratio. The fund’s sector allocations are similar to those of the benchmark, and its turnover is a modest 21%. The low turnover helps tax efficiency, while having a large number of holdings circumvents some of the liquidity issues that can arise when institutional investors trade large blocks of stock in small companies.

But the fund also differs from the benchmark in key ways. One-quarter to one-third of the stocks in the fund are found outside the Russell index. The outliers are mainly micro-caps too small for the bogey. Bergson likes these “smallest of the small” because they’ve historically outperformed the larger members of the small-cap universe over the long term. “The small-cap premium is not uniformly distributed,” he says. “A disproportionate portion of that premium comes from micro-caps that are often below where the benchmark cuts off.”

In addition to having more emphasis on micro-caps, the fund also significantly differs from the index in its higher return on equity (ROE), which reflects the amount of net income returned as a percentage of shareholder equity. The ROE of companies in the fund is 8.1%, while it’s only 5.4% for the Russell benchmark. That higher indicator is a sign of quality, suggesting the stocks in the fund produce income more efficiently for every shareholder dollar than the benchmark as a whole.

Although Bergson doesn’t aim for the top of the performance charts, he often beats most of his peers, and the fund’s consistent rules-based approach and resilience in down markets is notable. It beat its benchmark in six of the 10 calendar years between 2009 and 2018, and did better than its Morningstar small-cap blend category peers in eight of those years. It held up particularly well against both those bogeys in years when small-cap stocks produced negative returns, including 2015 and 2018. Bergson credits the fund’s quality bias for much of that resilience.

But there are also times when the fund underperforms. That happened between 2016 and 2018, for example, when investors took a risk-on stance and lower-quality stocks outperformed those with shinier financial characteristics. The period is a reminder that factors, even when they are combined for diversification, can face bouts of cyclicality and portfolios can be susceptible to periods of poor relative performance.

But for investors with patience, consistent wins can translate into returns that beat those of both peers and the benchmark over the long term. Over the 10-year period ending June 30, the Northern Trust fund’s 13.69% average annual return beat its Morningstar peer group by nearly 1 percentage point and slightly exceeded that of the Russell 2000.

At least some credit for that outperformance against other small-cap funds comes from an expense ratio of 0.65%, which is about half of what a typical actively managed fund in the category charges. The fund also keeps expenses low by minimizing trading costs, keeping turnover low and relying mainly on computer-driven quantitative analysis rather than a cadre of expensive fundamental analysts. But these qualities also take the investment process away from pure indexing. “We think of it as a quant-active approach,” Bergson says.

Whatever style label he uses, the 54-year-old didn’t follow the traditional route to investment management. He began his career as an architect, but after a few years in the field felt restless and went on to get a graduate degree from MIT in real estate development. After honing his quantitative skills at a real estate consulting firm, he joined Northern Trust in 1997 and began managing small-cap portfolios for institutional investors two years later. Today he’s responsible for several small-cap equity strategies representing more than $4.4 billion in assets.

Small-Cap Edge Prevails

Because small-cap companies tend to outperform larger ones over the long term, a smaller company size is considered a favorable factor. Still, large caps have taken the lead recently. Over the five years ending July 31, for example, the S&P 500 posted an annualized return of 11.34% while the Russell 2000 lagged with only 8.53%. The performance gap reached a historically high level in June 2019, when large caps were up nearly 10% for the year while small caps were down more than 8%.

A number of external forces have contributed to the unusual situation. The increased globalization of world markets has favored large companies, which tend to derive more of their sales from foreign sources, and investors often gravitate to blue chips in times of uncertainty.

But a number of factors could be turning the tide. Small company stock valuations are “on the cheap side” next to those of large companies, says Bergson. The threat of tariffs has more of an impact on larger companies, which typically have a stronger foreign sales presence than smaller ones. A strengthening dollar, which makes goods produced in the U.S. more expensive overseas than non-U.S. goods, also hurts small companies less. And Bergson points out that the advance of large company stocks has not been uniform. Financials, for example, have struggled in an environment of low interest rates.

Although he won’t put a time frame on when small caps are likely to outperform large caps, Bergson believes that the “small-cap premium,” which gives those companies an edge, is still in play. “Over the long term, small-cap companies have demonstrated an advantage over large caps. The small-size factor is among several equity factors that research shows have outperformed the broad market dominated by large caps over the past 50 years.”