What’s the value in “value” emerging markets investing? After all, for many investors the allure of emerging markets is their tantalizing growth prospects, fueled by the sector’s favorable one-two punch of a youthful population demographic and potential for a blossoming middle-class consumer society. Given those features, emerging markets are generally viewed as a way to juice the growth profile of an equity portfolio, with the value component to be filled in with supposedly cheaper and/or less risky U.S. or other developed market stocks.

But value investing isn’t just about finding stocks with low price-to-whatever multiples. “Because people pursue growth in the emerging markets universe, it stands to reason that there’s a lot of latent value there,” says Paul Espinosa, lead portfolio manager at the Seafarer Overseas Value Fund. “It’s not that I don’t look at growth, but I minimize that factor in what I look for.”

One of the key metrics that Espinosa and his team focus on is the spread between the return on equity and the cost of equity of a company. According to Seafarer, the team looks for a return on equity significantly higher than the cost of equity throughout most of the economic cycle. This analysis forces them to understand the actual operations of the business and the cost of its growth, instead of just the growth it delivers. They believe this process can produce better investment results.

“To the extent that most EM investors are focused on the growth factor, they leave these other two factors on the table for the picking that can be bought at very attractive prices. That’s the opportunity,” Espinosa says.

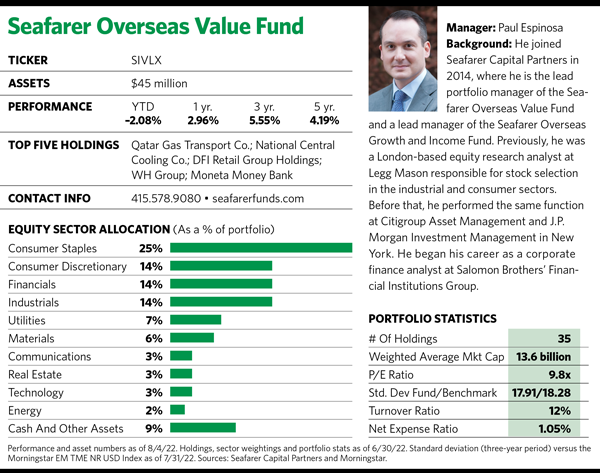

And for the most part this approach has meant success since the Seafarer Overseas Value Fund launched in 2016. According to Morningstar, the fund has been a top-quartile performer in the one-, three- and five-year periods within its diversified emerging markets category. And year to date as of early August, it had massively outperformed its peers and its Morningstar designated benchmark index; it lost only about 2%, which outperformed the category by 17 percentage points and the benchmark by 14 percentage points.

Seafarer Capital Partners is an investment advisor founded and run by Andrew Foster, a former high-level investment executive at Matthews Asia. The firm also runs the Seafarer Overseas Growth And Income Fund, which is the larger of the company’s two funds. That fund holds more traditional and familiar large-cap overseas companies, whereas the Seafarer Overseas Value Fund offers a more eclectic and diversified portfolio that includes recent top-10 holdings from such places as Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and the Czech Republic. Among other holdings within the portfolio’s 35 constituents are companies that hail from Georgia, Peru and Vietnam, along with a healthy dollop of smaller, lesser-known companies listed in China/Hong Kong.

And despite its emphasis on emerging markets, the fund invests in companies headquartered in developed markets that have significant operations in developing nations.

Old-School Investing

Foster is a co-manager at the Overseas Value Fund, and analyst Brent Clayton is also part of the investment team. But Espinosa is the main driver of the fund’s strategy, which he says is an amalgamation of everything he’s learned over the years at previous jobs.

The fund employs a bottom-up security selection process based on fundamental research, and it doesn’t rely on algorithms to point the way. “The process is labor-intensive,” Espinosa explains. “I like to think of it as old-school investing. We don’t start from the benchmark at all. It’s about pencil and paper, and doing the numbers.”

He posits that investing strategies based on artificial intelligence and reams of statistics can produce data that sometimes lack context. “The fact you can analyze data doesn’t mean that you have information,” he continues. “Information comes from thinking, so this is about setting the numbers first, and then meeting the companies and talking to management and then putting the numbers together.”

He adds that his investment process isn’t about trying to capture which sector or company will work in the next year, but rather how in real terms he will get a dollar return above inflation from investing in a particular company at a particular price.

Espinosa uses screens for seven categories of value in emerging markets to identify long-term investments. These categories are related to a company’s balance sheet and cash flows and include measures such as balance sheet liquidity (cash or highly liquid assets undervalued by the market) and a company’s breakup value (when its liquidation value exceeds its market capitalization).

“The seven categories try to define value in terms of their fundamental drivers and not just in terms of multiples, which I think is the problem with the traditional definition of value of low multiples. If you do that, you could fall into traps,” Espinosa says.

He incorporates these categories with other attributes of a company, such as the spread between its return on equity and cost of equity (or ROE-COE spread), along with a company’s resilience (which he defines as its ability to prolong the growth and income stage of its life cycle for a long period) and its global validation (the company’s proven ability to sustain and defend its source of value). Espinosa also seeks a valuation he believes is consistent with the targeted minimum long-term rate of return.

“I’m not pursuing countries or sectors; it’s really all about the companies,” Espinosa says, adding that he and his team compile a portfolio of companies that each have their own individual drivers. “In my opinion, diversifying across drivers of investment return gives you a better chance of performing through the cycle. I don’t care what factor is outperforming right now. I have my diversity of companies that will drive the investment return, and I think that adds value.”

Finding Gems

The end result is a multi-capitalization portfolio where mid-caps represented 38% of the holdings at the end of June, followed by a 32% weighting in large caps and 22% in small caps. (The remaining 9% was in cash and other assets.) Countries in East and South Asia made up 55% of the fund’s assets, while Latin America and the Middle East/Africa region were the next biggest weightings at 13% and 12%, respectively.

Beyond using his valuation screens to find potential portfolio candidates, Espinosa uncovers what he calls investing “gems” by traveling quarterly for roughly two weeks at a time to less-trafficked parts of the investment world, attending industry conferences and doing company visits. He sometimes finds well-run companies in unlikely places.

“There are good companies everywhere,” he says. “Many investors consider emerging markets or frontier markets as risky. That can be true in a general sense, but when you get into company specifics there are gems everywhere.”

But not all gems are investable. For example, he notes, there are some brewers in Africa he would’ve invested in but didn’t because their equities were too illiquid. But beer has universal appeal, and the Overseas Value Fund taps into that industry segment by investing in Anheuser-Busch InBev, a Belgium-based multinational brewing giant (the result of InBev’s acquisition of Anheuser-Busch in 2008), as well as its subsidiary, Brazilian brewer Ambev.

In a white paper from last September, Espinosa explained that his fund took a stake in Ambev after he and his team ascertained that its high ROE-COE spread provided a significant buffer to continue being profitable even if Brazil suffers a recession and the Brazilian real devalues.

In an interview, he explains that AB InBev and Ambev are different companies from a portfolio perspective because they bring different things to the table. AB InBev is levered, pays a low dividend and is a deleveraging story, while Ambev has net cash and pays a high dividend.

“They offer a diversity of the drivers of return,” Espinosa says. “I expect investment returns from both but they’ll do it differently—one from lowering debt and increasing the dividend, the other by increasing its volumes and margins due to investments in terms of changing how it operates.”

Espinosa offers that investors typically find value-oriented investments in efficient, developed markets by spotting some sort of trouble (without which a company likely wouldn’t be cheap in the first place). But in the emerging markets, he says, lots of well-run companies are undervalued simply because investors aren’t turning over enough rocks to find those gems.

“To me it’s easy pickings, and we haven’t had to pursue trouble to find value,” he says. “In our opinion, that market is mature enough where you can pursue other strategies that look at other factors, and you can get them at good prices because no one is pursuing them.”