It helps to be prepared for medical emergencies. As the coronavirus spreads, health officials are scurrying to ensure medical facilities have adequate supplies to deal with the rising caseload.

As the economic consequences of the coronavirus spread, policymakers are struggling to formulate their reactions. Unless they improve their preparedness, it could mean the end of the global expansion.

Central banks have done their part. This week, the Bank of England surprised with a half-point rate cut, and announced a funds-for-lending program targeting small businesses. The European Central Bank (ECB) chipped in by expanding its quantitative easing program. The U.S. Federal Reserve injected $1.5 trillion of liquidity into the financial system to keep order, and is likely to reduce interest rates further at its meeting next week (if not before).

Monetary measures can help support financial conditions and bolster flagging market sentiment. But they are not the best tools for the task at hand. The lag time between central bank action and economic reaction means that recent movements may not reach their maximum benefit until after viral contagion and the related supply chain disruptions have eased.

On Thursday, ECB President Christine Lagarde called for “an ambitious and coordinated fiscal policy response” to address the spreading malaise. Her comments were primarily aimed at Berlin and Washington. Properly structured and sized, additional spending can add immediate impetus to economic activity and target it to the areas of greatest need.

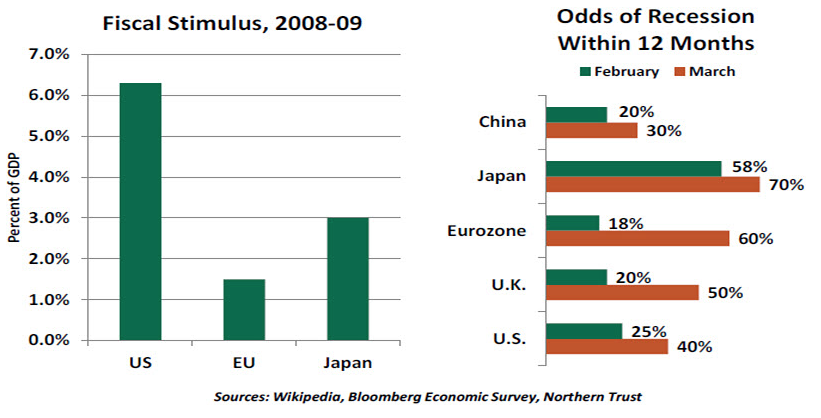

The substantial fiscal programs of late 2008 and 2009 helped hasten economic recovery and launch the long bull market that ended this week.

Fiscal policy takes more time to formulate, given more complex governance (and significantly more complex politics) surrounding the process. A range of economic actors and sectors will ask for relief, and debate will center on whether to stimulate demand with direct government spending, tax reductions, or checks to households.

Not surprisingly, China has moved most forcefully. In response to the virus, it has implemented a range of measures to support activity and minimize financial distress. The scale of its reaction matched the scale of the challenge, and there are signs of recovery in Chinese activity. While there may be costs to pay later, those costs would likely pale in comparison to allowing the economy to decline further.

Western governments have been nowhere near as quick or as bold. A few billion dollars, euros, and pounds have been appropriated to assist, but the amounts are a drop in the bucket for economies that are trillions of dollars in size. The United States has authorized only $8 billion thus far, a paltry sum compared to the $900 billion of fiscal stimulus passed in 2008 and 2009. Cautious measures fall well short of the “shock and awe” that will be needed to arrest any declines in consumer, business and market confidence.

The American response to the spreading crisis has been entirely insufficient. The process has been hindered by a delayed recognition of the scale of the challenge, which led to delays in the design of appropriate responses. It isn’t surprising that the White House and Congress began on somewhat different tracks, but the magnitude of the occasion should prompt much more rapid coalescence. Markets have been anxiously awaiting a resolution.

There are elements of support that make immediate sense. Medical aid to facilitate testing and treatment, employment support for those who may be furloughed or fired, programs targeted to industries most severely impacted, and aid to states to head off local contraction would all have powerful impacts in the near-term. The programs must be sizeable: at least 1% of gross domestic product (more than $200 billion for the U.S., €135 billion for the eurozone). As we go to press, a package of that scale is reportedly being finalized in Washington; Europe will require more time.

Ideally, economic stimulus should be well coordinated across countries. But the diminished standing of global interactions and global commerce is making this difficult. At moments like these, the recent tendency of countries to go their own way is jeopardizing the health and wealth of nations. They need to come together—right now.

The Staying Put Option

Ryan reviews the rapid slowdown in travel, and deliberates whether to add to it.

My family and I were slow to decide on our summer travel plans. In this case, procrastination worked to our advantage. Conversations that began with open-ended daydreaming about destinations abroad took a darker turn: Is travel a good idea in the midst of a health crisis?

Epidemiologists have shared clear guidance that we should all avoid gatherings of large numbers of people. The recent spate of trade show and conference cancellations reflects sound judgment. Corporate travel departments are uniformly reducing business travel, not wanting to put their employees in any danger. Tourists now face the choice of whether to rearrange their plans, though new travel restrictions may make the decision for them.

Travel is a cyclical sector. We expect less travel in any economic downturn: Employers will limit travel expenses, and households can get by without a vacation. But such decisions usually follow diminished economic circumstances instead of causing them. The ordering may be reversed this time around. Airlines and hotels are already seeing mass cancellations. Their employees are braced for a reduction in hours if the slowdown is temporary, or layoffs if demand stays depressed.

International airlines started by reducing their service to areas highly impacted by COVID-19, citing low demand for these routes, safety concerns for their employees and temporary government prohibitions on arrivals from these destinations. But as the virus has spread, so has a nervous attitude toward travel and mass gatherings. An increasing number of events (including a sizeable fraction of the world’s sporting contests) have been cancelled, and an increasing number of tourist attractions have been shuttered.

When these things occur, the knock-on losses to the host city are legion: hotel rooms sit empty, restaurants welcome fewer patrons, and rideshare drivers find fewer fares. Sales tax receipts fall, affecting local governments.

Halted tourism is especially painful, as it is usually a permanent loss. While deferred purchases of durable goods can be made up as economic conditions improve, trips not taken are not recovered. Airplanes flying with empty seats today will not recapture that revenue another time. Cancelled conferences are rarely rescheduled. A family that decides against a holiday this year is unlikely to book two trips to make up for it next year.

Any lost hours or reduced payrolls in the travel and hospitality sector are likely to fall first on the lowest-paid workers. Throughout the current expansion, job growth in the hospitality sector has consistently outpaced that of the economy as a whole. The sector has welcomed re-entrants to the labor force, boosting the participation rate. This labor-intensive sector needs many cleaners, servers, cooks and drivers when the economy is thriving; when conditions cool, these front-line workers are the first to be culled.

Travel and entertainment are important sectors of the U.S. economy. Restaurants, hotels, transportation and recreation add up to about 15% of U.S. consumer spending. Further, over the past decade the U.S. had seen a steady rise in the number of leisure travelers from abroad, who spend a considerable sum of money while here. In 2018, nearly 80 million international visitors arrived, spending over $156 billion. China’s share of tourist arrivals also grew as its economy thrived, accounting for nearly three million arrivals in recent years. These trips are vital to the domestic economy, as the industry employs nearly 9 million people.

Reticence on the part of travelers was already a poor omen for hospitality workers. This week’s travel ban from the White House added further gloom to the industry outlook. The new prohibition on any foreign traveler entering the U.S. from continental Europe took the whole travel industry by surprise. The restriction affects 3,500 flights per week in a busy airspace, with only a day of notice. The pronouncement required further clarification that U.S. citizens and permanent residents may return to the country, and that goods imports are not restricted—but cargo also arrives in the hold of passenger flights that are now disrupted. Airline share prices plummeted, further shocking an industry already under pressure.

Targeted support to these affected industries may take shape with forthcoming fiscal interventions; if governments can keep companies afloat and stem layoffs, such intervention will be worthwhile. For now, airlines and hotels are offering discounts and more flexible terms to convince hesitant travelers to get back on the road. Indeed, airlines’ waiver of future rebooking fees convinced me to go ahead and reserve my family’s summer flights. For a range of reasons, I am hoping we’ll depart on schedule this July.

Bearing The Brent

The COVID-19 outbreak has led to financial market corrections and weaker demand across sectors. Under these conditions, a modest oil price decline would be no surprise. However, the dramatic price drop that followed last Friday’s collapse of discussions among crude producers sent shock waves through financial markets.

Tensions between Russia and Saudi Arabia pushed oil prices off a cliff. The 24% decline seen last Monday was the biggest single-day drop since the Gulf War in 1991. After Russia refused to lower output, Saudi Arabia slashed oil prices with plans to increase production. Shortly after, Russia indicated similar intent, bringing back memories of 2014 when Saudi Arabia, Russia and the U.S. competed for greater market share. As production escalated, prices plummeted.

Tumbling oil prices couldn’t have come at a worse time for highly oil-dependent economies. While advanced economies are attempting to dampen the economic shock from the virus outbreak in a coordinated way, the oil price war has exposed the absence of coordination between major oil producers. Dealing with the virus threat will be expensive, and lower oil prices will only add to the rising fiscal pressure on petro-economies, particularly in Venezuela (Russia’s ally) and Iran (Saudi Arabia’s main opponent), which has 9,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases.

The move by Saudi Arabia to lower prices and ramp up production to garner market share is seen by many observers as an attempt to bring Russia back to the negotiating table. The price war will hurt Russia, but every oil exporter will feel pain, including Saudi Arabia. Lower oil prices, if sustained, will likely create a big fiscal hole for oil-dependent nations.

According to International Monetary Fund estimates, the fiscal breakeven—the price of oil that balances the government’s budget—is well above current levels in several nations. It is close to $200 a barrel for Iran and over $80 for Saudi Arabia. Russia’s breakeven price of $40 and its floating currency give it a greater cushion against a price decline.

Saudi Arabia’s financial reserves and its sovereign wealth fund provide a buffer, but the cushion is smaller than it was in 2014. With a much higher fiscal breakeven level, Saudi’s public finances are already under strain. According to Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank, if government spending is not adjusted, a price of $35 for Brent crude would push Saudi Arabia’s budget deficit from an estimated 6.4% to about 15% of gross domestic product (GDP) this year. A prolonged volume/price war will jeopardize the country’s economic modernization program and could weaken Mohammed bin Salman’s grip on power as the Saudi populace grows disaffected.

Though the U.S. is the world’s largest energy producer, its diverse economy makes it less vulnerable than Russia and the Middle East. But Oxford Economics estimates that a sustained $30 plunge in oil prices would shave off 0.2% of U.S. GDP due to reduced investment in the shale sector. The crash in oil prices could prompt a wave of defaults among producers with weak balance sheets and credit ratings.

Economic weakening can lead to civil unrest. The slump of recent years has already bred that sentiment across commodity-driven economies like Iran and Russia. The dual shocks of a price war and COVID-19 will be another litmus test of their political systems, especially for those with less fiscal room. As we went to press, the oil price had pared some of its recent losses amid renewed hope for talks between Saudi Arabia and Russia. We are hopeful this brinkmanship will be resolved before it leads to a price war none can afford.

Carl R. Tannenbaum is executive vice president and chief economist at Northern Trust. Ryan James Boyle is a vice president and senior economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. Vaibhav Tandon is an associate economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust.