Even fans of student debt relief will admit it doesn't solve the core problem of crushing higher education costs. For that, debt-forgiveness proponents such as Bernie Sanders and education economist Sue Dynarski have a long-term solution: free college.

They have a point. If we're going to burden the tax base to pay for the nation's college students through debt forgiveness, we might as well be more upfront about it. Just be prepared for the result. Free college will not only worsen the quality of American universities, currently the best in the world, and mean fewer resources for students, it would also be more regressive and would deepen inequality compared with a system where students pay or take out debt.

Free college, like universal health care, is one of those things that exist in Europe that Americans love to idealize. In Europe, most universities are public and France, Germany, Sweden and Scotland don’t charge fees to domestic students. But like just health care, nothing is ever really free. Free college is paid for with taxpayer money, which is always in short supply, and that often results in lower-quality services in the form of over-crowded classrooms and crumbling buildings. It's popular to make fun of the plush facilities on American college campuses, but a lot of the spending on students is valuable. More spending per student is one big reason why British and American universities dominate global rankings.

Limited resources also means rationing. And when capacity is limited, places tend to go to students from higher-income families. They get better secondary educations and appear more qualified when it comes to admissions in competitive schools. In Germany, about three-quarters of adult college graduates send their children to college, while only 25% of adults without degrees have children in college.

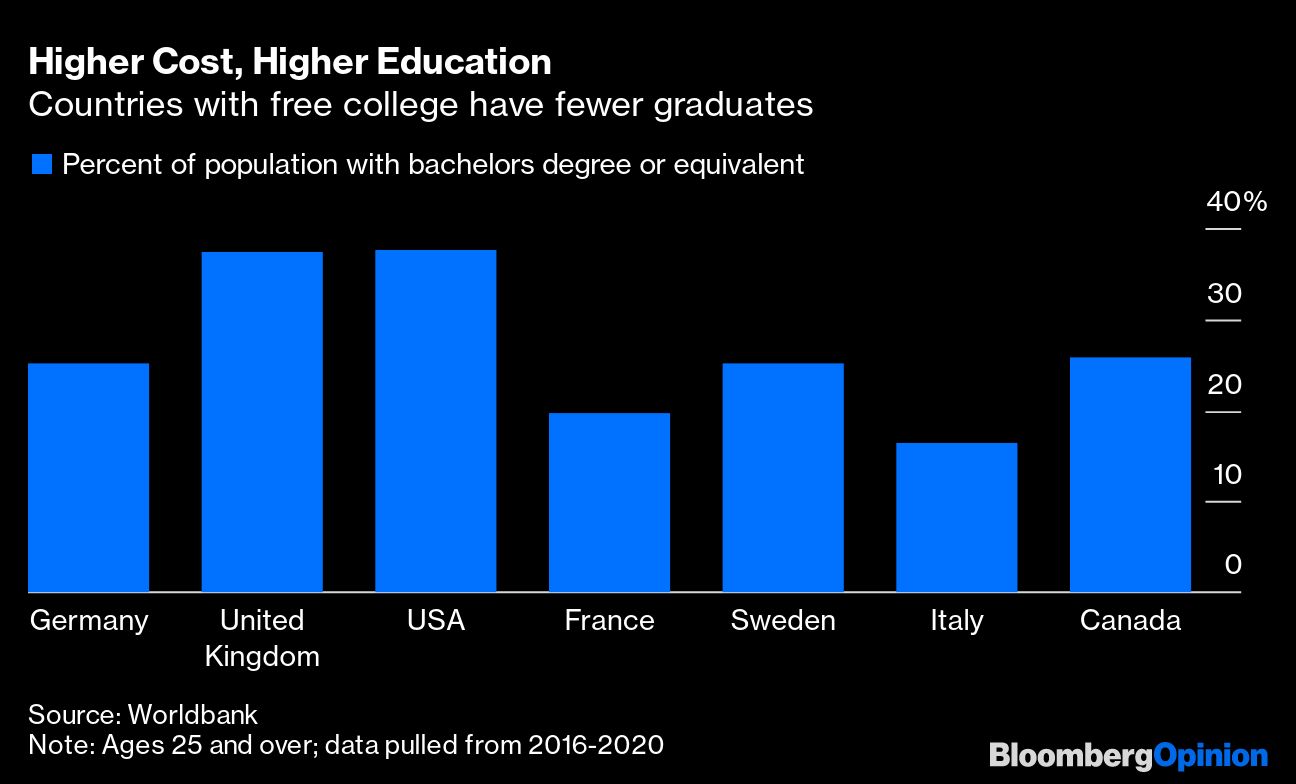

The figure below shows the share of the population (25 and above) with a bachelor’s degree (or equivalent) in different countries between 2016 and 2020. The countries that offer free or very cheap college have much lower graduation rates than the higher-cost US and UK.

Perhaps lower graduation rates would be fine, since it seems like too many people go to college anyway. But free college doesn’t mean more vocational training. Germany briefly charged fees starting in 2006. But after lots of protest it returned to free college in 2014. Once they removed fees, more students went to university, and this reduced the number of students who enrolled in vocational schools.

The United Kingdom also offers a useful case study. Until 1998 college was free for English students. At first fees were modest, but they now exceed £9,000 per year (typically about $12,000 — more than many state schools in the US), which are financed with loans that graduates pay back based on their income when they start work. One study found that charging fees resulted in more students attending university; it narrowed the participation gap between students from high- and low-income families and more resources were spent per student.

Meanwhile, Scotland went tuition-free for Scottish and European (until the UK left the EU) students. A study by Lucy Hunter Blackburn of the University of Edinburgh estimates that the result was many low-income Scottish students ended up taking on more debt than their English peers because they had to get loans to pay for living expenses. Up until 2016, English students from low-income families could also get grants to pay for living expenses (now living expenses are also covered by loans) while Scottish students had to take out loans or rely on their families. She concludes that free tuition in Scotland amounted to a £20 million (at the time, $30.9 million) transfer from low-income to high-income families. And while enrollment of students from low-income families increased all over the UK in the last 25 years, England experienced more growth despite charging fees.

Based on the European experience, free college is not the solution to financing education if we want a system that reduces inequality and leaves students with little debt.

Free college might look different in the US because of the extensive network of private institutions. We could limit free tuition to public universities and let private schools such as Harvard and smaller liberal arts colleges continue to charge fees. In some ways that would make the education system better — odds are many private colleges, especially the low-value ones, would close because fewer students would be willing to pay fees when they have a free option.

The only private universities that would survive would have to offer very high value or have very large endowments. But fewer colleges leaves fewer spots for students overall, and even more competition for the few places available at high-quality state schools — especially for students who are barely qualifying now, but end up benefiting from their education through much higher lifetime earnings. When it comes to completion and getting some value out of education, Dynarski points out that the quality of the school is what matters. Yet free college undermines quality because it means less spending per student and doesn’t necessarily lead to higher completion rates .

Free college at public universities risks further entrenching inequality by worsening what is already a two-tier system in US higher education. Inequality will only be exacerbated if the high cost of free public education means there’s less government money to subsidize loans for lower-income students who want to attend good quality, private schools that still charge tuition.

One of the benefits of university for students from low-income families is the exposure they get to students from more privileged backgrounds . A more disparate two-tier system undermines that process and further segregates our economy and society.

The US higher education system, which charges fees and offers need-based aid and loans is clunky and often wasteful. There needs to be more scrutiny over needless spending, tuition inflation, how loans are structured and schools that offer no value.

But the current system largely works and is better than most other countries. The overwhelming majority of people who graduate from college are rewarded with higher lifetime earnings, and many Americans do go to college. Moving to free college would mean students would still have lots of debt to pay their living expenses and the quality of public education would decline. The better solution is to reform student loans and keep university fees.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of “An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.”