Financial planning is not static or one-dimensional. People’s priorities change, as do their time frames, as do the risks they are willing to take in life. Their confidence in their investment portfolios is reflected in the interplay of the amount of time they have and the amount of risk they are willing to take. Financial advisors know this from experience, and their clients know it instinctively.

Still, a composite view of aggregated return and risk characteristics in the form of crunched numbers can be too abstract to appeal to flesh and blood investors and the psychological confidence they have in their own investments. That’s why we find it’s better to break out portfolios into multiple components to map people’s investments to their different priorities and time frames, whether it’s into higher risk investments that target lower priority and longer-term objectives, or into lower risk investments that address high priority and more immediate objectives.

Priorities

Consider a financial take on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In the bottom rungs, investors seek bulwarks against loss and deprivation, and they hope to maintain a safe and reasonable lifestyle. As they go up the rungs of the ladder, they might pursue more ambitious objectives and “self-actualizing” goals like having a second home, retiring early, or having resources to provide generous support for their children or for charities.

Time Frame

The time dimension is also crucial to investing. Meeting next month’s mortgage payment is not only a high priority but also requires thinking for the very short term, while an objective like, “I want to live at least at my current standard of living when I retire 20 years from now” can only be contemplated and planned from a distance. Investment choices and their related risk characteristics also change with the investment horizon. Markets can move violently in the short term, but in the long term, capital market assumptions become an increasingly reliable guide for expectations.

Risk

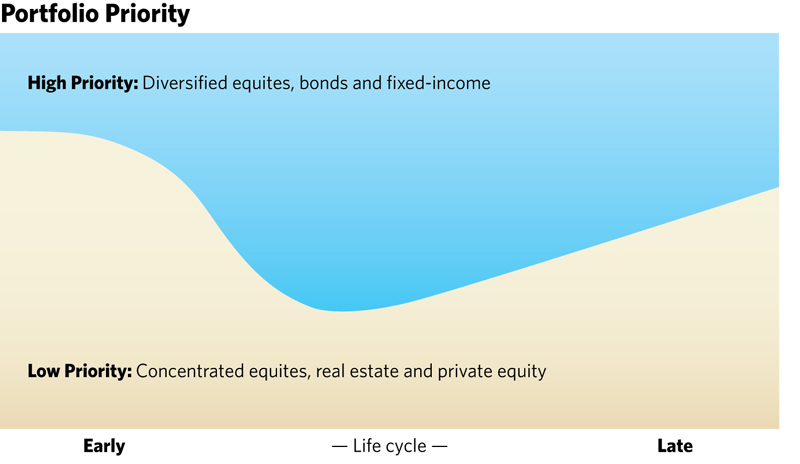

The difference in people’s investment risk can become stark as they move from high priority to low priority objectives—and more dramatic than what’s captured by most risk models. Lower risk investments tend to be liquid and operate in efficient markets that have fungible, “bite sized” units with plenty of publicly available information and many investors competing for advantage. In markets like that, advisors expect the risk assessment to be fairly reliable. As the risks ramp up for longer-term investments, they become more opaque. The returns here might turn out to be extraordinarily good, the markets relatively inefficient and the features of the investments more unique, but they come with large price tags that limit investor entry, they provide limited public information, offer less liquidity and suffer from having fewer market participants.

Allocation

Advisors will have an easier time explaining investment plans to clients if they can tie the sub-allocations of their portfolios to their objectives. Just as higher-priority and short-term objectives should be linked to investments with lower risk and more liquidity, lower-priority and long-term objectives can be appropriately pursued in less diversified and less liquid securities—holdings of specific stocks, private equities, real estate or hedge funds, for instance—that tend to be less efficient but have the potential for a high upside.

Breaking the risks up this way when designing portfolio distribution is a departure from the symmetric, bell-shaped normal distribution usually used for risk analysis. It dampens the downside tail to provide a buttress against big losses while extending the upside—albeit with a small probability—to allow for aspirational gains. The expected downside tail is skinnier, the upside tail is fatter.