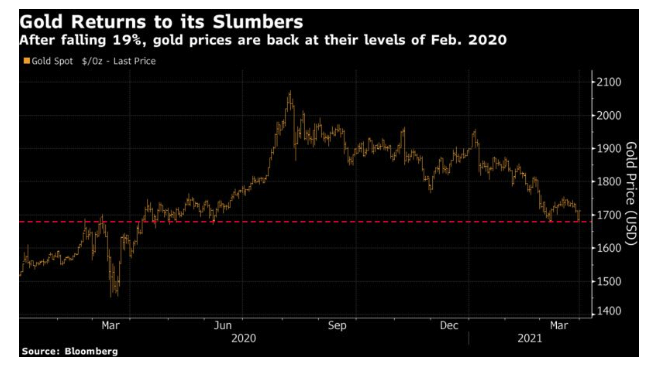

As 2021’s first quarter comes to an end, gold hasn’t enjoyed a great time of it. The precious metal has tumbled 19% from its high last August and is back where it was in February of last year, before the pandemic hit the developed world.

Gold did at least manage to rally in Wednesday trading, as traders took heart from its ability to stop short of the 20% fall that would have qualified as a bear market. But the problems for gold are still significant, and come as something of a surprise. Last August, I wrote a Points of Return on the gold price, which looked at various arguments by analysts and concluded that “absent a swift victory over the virus, all of these... methodologies suggest that there is far more room for gold to rise than to fall.”

Progress in the fight against the Covid has arguably been better than expected since then. The third wave that hit the U.S., and the second wave in Europe, shattered hopes that populations might already be close to “herd immunity,” but progress in producing vaccines has been far faster than expected then. This has, as predicted, made the environment less favorable for gold. Still, the extent of the decline requires some explanation.

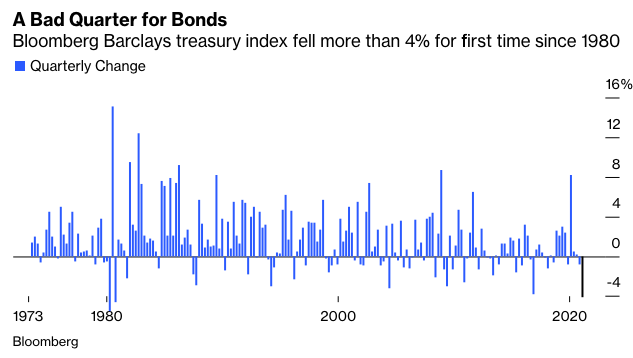

First, and most important, this has been the worst quarter for bonds in some decades. These facts may well be related.

Not even the Federal Reserve’s insistence that it will keep financial conditions as lenient as possible has been enough to keep longer-dated bond yields down. As a result, the Bloomberg Barclays Treasuries index has fallen more than 4% for the quarter, the first time this has happened since the first and third quarters of 1980, when stagflation was at its height.

The assumption in the market, correct or otherwise, is that more inflation is coming down the pike, and that the Fed will have to raise rates in due course to deal with it. What is interesting is exactly when inflation will arrive; that has important implications for gold. Although the metal is regarded as an inflation hedge, it isn’t as simple as that. It is more sensitive to interest rates. When rates rise, because of fears of long-term inflation, gold can be expected to fall. Hence, the price has taken a horrible tumble even as markets brace for inflation.

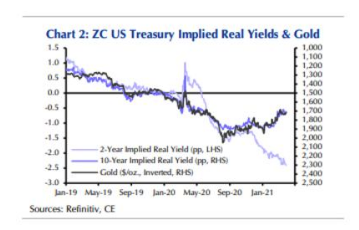

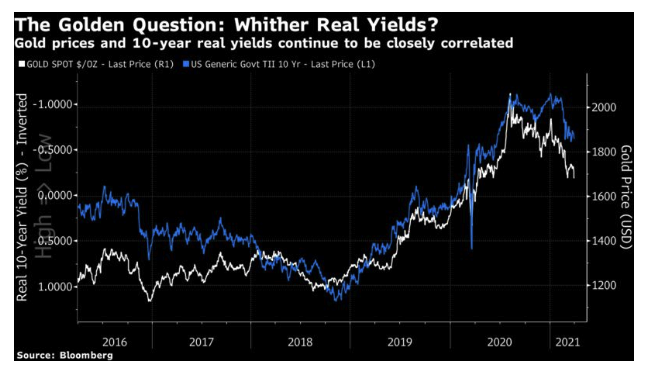

John Higgins of Capital Economics Ltd. in London produced implicit performance for the real yields of notional zero-coupon two- and 10-year bonds. Normally, they track each other, but they have parted company dramatically this year, reflecting the belief that the Fed will be lenient for a while (keeping short rates low), and will have to intervene more strongly with higher rates in the longer term. Gold, unfortunately for investors, follows longer-dated bond yields:

There are reasons for this. Gold yields nothing and lasts forever, so should be treated like a zero-coupon long-duration asset. Higher rates make its lack of yield more unappealing. Low rates make it look better. The lowest real yields in history, as seen last year, were enough to bring the metal to an all-time high in nominal terms. So it shouldn’t be that surprising that, with real yields rising this quarter, the gold price fell.

There’s a little more to it than that, though. If anything, gold seems to have fallen by more than might have been indicated by the rise in real yields. Other factors explain this.

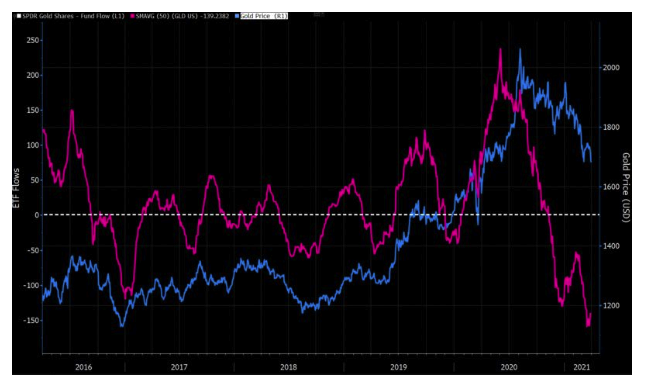

Investor demand, especially through the exchange-traded funds beloved by retail investors, is ever more important. After heavy inflows during the Covid shock to the iShares gold ETF generally known by its GLD ticker symbol, investors have started to yank cash in a big way. The chart shows the gold price in blue, against the 50-day moving average for fund flows into GLD. The outflows appear to have had a big impact:

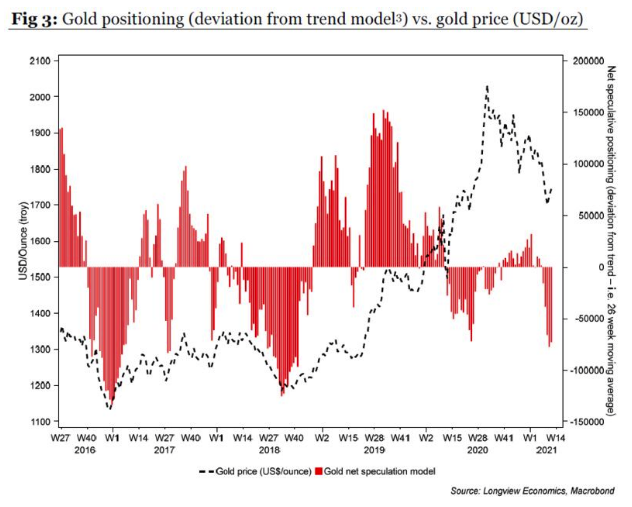

If we look at futures positions, we similarly see a sharp turn against gold in recent weeks. The following chart from Longview Economics Ltd. of London looks at variations from the trend, to account for the fact that gold positioning tends always to be “long.”

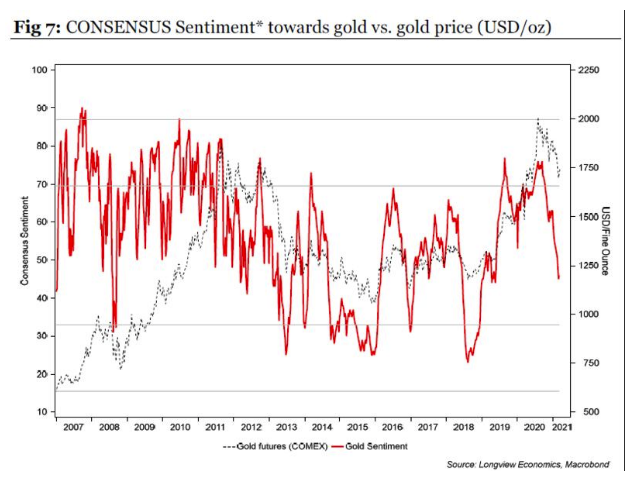

Longview also shows that investor sentiment around the outlook has turned much more negative, using data on consensus predictions of big institutions collated by Consensus Inc., a research group. It is now at levels that are typically bullish for the future price:

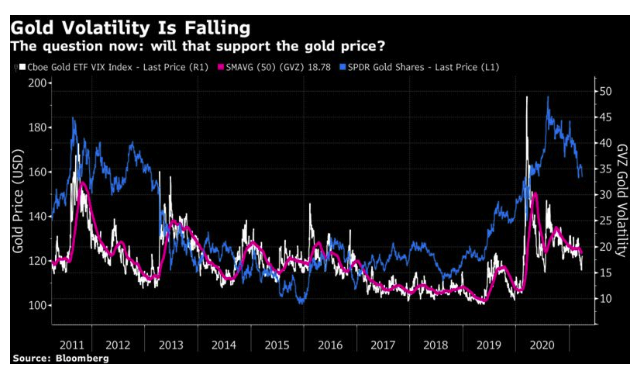

Another potentially bullish sign is the fall in volatility, measured by activity in the options market for gold ETFs in the same way that the VIX index for equities is measured. Calmer conditions probably create better prospects:

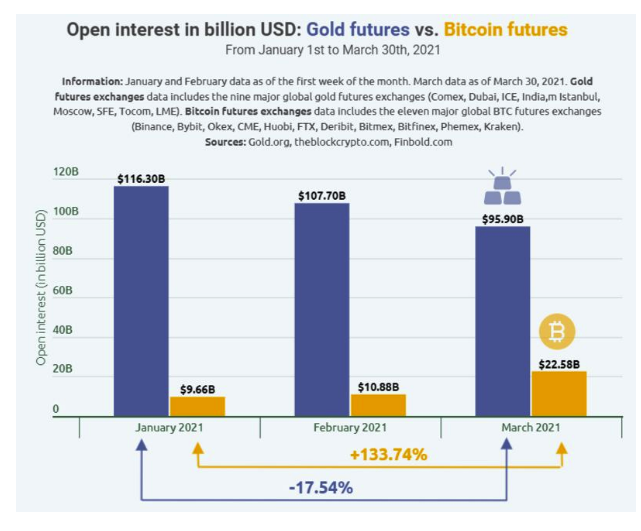

There is one other element to bring in. Gold has new competitors in the cryptocurrency space. Like gold, bitcoin and the like appeal to people who want to bet not only on weakness in fiat currencies that will show up through inflation, but also to show their disapproval of government and its growing powers. Bitcoin continues to be one of the remarkable stories of the age, and it would make sense if it were at the margin taking demand away from gold. These numbers come from the Finbold website and suggest that trading volumes in bitcoin futures are rising fast while trading in gold has declined:

Another crash for bitcoin, very easy to imagine, would probably be good for gold.

Where does all this leave us? For those who think that the bond market has given us a head fake, and that yields will consolidate or even fall over the next few months and years, gold looks like an interesting way to play that. If the inflation scare takes greater hold and 10-year real yields rise, gold looks at risk of a true bear market. But, as in August, nothing matters more than how the economy emerges from the pandemic and the resulting effect on bond yields.

Gold Is The Measure

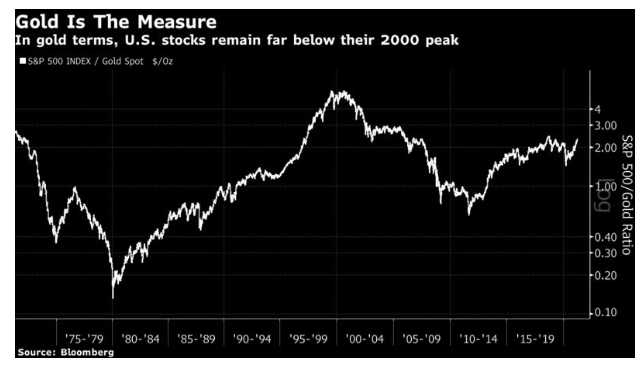

It’s always interesting to look at the stock market in terms of gold. In the long run the ratio between the two, one benefiting from risk appetite and the other from aversion, speaks volumes about the financial and market regime in which we find ourselves. This is how the S&P 500 in gold terms (the ratio of the S&P to the gold price) has performed over the last 50 years—since just before the collapse of the Bretton Woods exchange-rate regime, which allowed gold to vary against the dollar:

The financial history of the last half-century becomes much simpler. A horrific bear market takes hold throughout the 1970s, amid oil shocks and stagflation, to be followed by a scarcely interrupted two-decade-long bull market that finally went too far amid the internet boom. After that came a savage bear market that only reached bottom after the debt ceiling crisis of 2011, when investors grasped that the Fed’s quantitative easing bond purchases weren’t going to cause inflation. Since then there has been another bull market, though so far much slower than the one that preceded it. All of this coheres very well with subjective impressions of how financial conditions felt at the time.

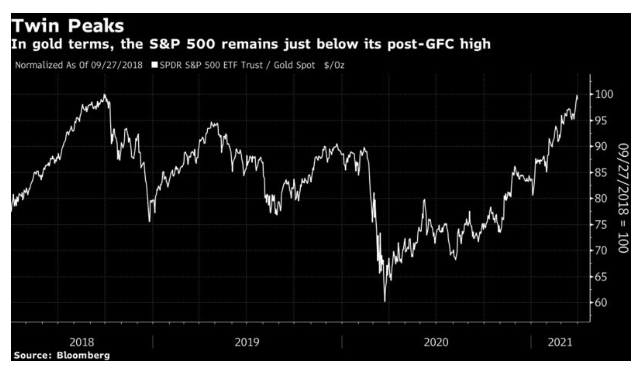

Are we still in a bull market on that basis? Probably, but the final day of the quarter produced an interesting quirk. With the gold price rallying, the S&P in gold terms fell slightly, leaving it just short of the post-dot-com high set at the end of September 2018.

How important is this measure? A lot can get clouded with political preconceptions. Depending on your point of view, gold is the ultimate measure of everything, or an illiquid and irrelevant relic whose value is in the eye of the beholder. But both numerator and denominator in the S&P/gold ratio are dependent to a great extent on bond yields, with stocks weathering higher yields much better than gold has done to date. Barring seriously bad news on the pandemic, it’s fair to expect the S&P in gold terms to take out its 2018 high before long.

Infrastructure Day

It looks like Infrastructure Day has finally arrived. President Joe Biden, an old man in a hurry, is moving quickly to assert his political advantage with a proposal for a $2.1 trillion splurge of infrastructure spending, financed in part by increasing corporate taxes. Anyone who has tried to travel around the U.S. in recent years will know that there are plenty enough worthwhile projects to justify that massive sum. And anyone who has observed the attempts to finance infrastructure projects across the world over the last decade will know that it’s difficult to get good plans financed and off the ground.

Biden is also showing a willingness to learn from his predecessors. He is definitely avoiding what is now regarded as Barack Obama’s mistake of setting his opening bid for a 2009 stimulus package too low. He is also reviving the Trump administration’s initial intense interest in ways to reform the tax code, and not merely cut rates.

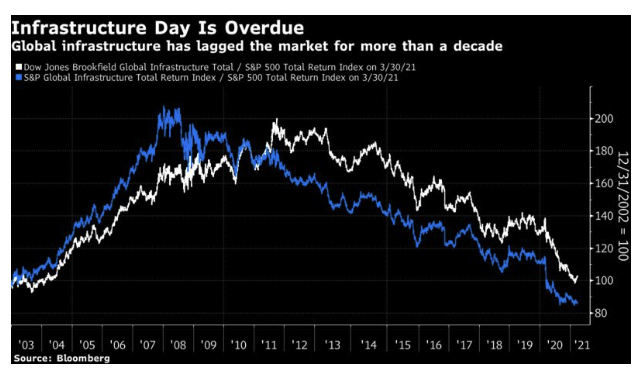

If (and it remains a big “if”) Biden can push a plan through, it might turn out to be a great time to buy infrastructure stocks, which have lagged ever further behind the market since the global financial crisis. They fared very well during the first years of this century on the back of the “BRICS” phenomenon, as investors rushed to finance the development of China and other emerging markets. Since the crisis, infrastructure’s underperformance has been persistent and painful:

The two indexes tell essentially the same story. The Dow Jones Brookfield Global Infrastructure index is a pure play, and has held up slightly better than the S&P Global Infrastructure index, which includes companies with broader businesses. At this point, a spending boost would do both a lot of good. As infrastructure projects, once built, tend to be competitively ring-fenced, with a reliable income stream, they could make a lot of sense.

Those less certain that Biden can pilot extremely contentious legislation through Congress should note that the market reaction was muted; bond yields moved close to the top of their recent range, but the market isn’t going on strike. U.S. stocks remain virtually at an all-time record. This is one case where markets and reality affect each other. If markets stay this unconcerned, the chances that Uncle Sam splashes a lot of money on building stuff look much better. If the bond or stock markets revolt, its chances are much weaker.

Survival Tips

Happy April Fools’ Day everyone (and happy anniversary to my parents, who had a sense of humor when they set their wedding date). This is a reminder to be on the watch for hoaxes as the day proceeds. This year, Volkswagen jumped the gun with a joke about changing its name to Voltswagen, which fooled plenty of people. This wasn’t surprising, as it came out in March. My colleague Chris Bryant describes this as German humor at its best—and VW stock is still higher than it was when the joke came out, so it was a lucrative stunt.

I don’t have the energy to come up with a good April fool, but I can offer two of the greatest British entries: a 1957 Panorama report on the BBC by Richard Dimbleby on the spaghetti harvest in northern Italy; and a travel supplement published by the Guardian in 1977 advertising the Indian Ocean island paradise of San Serriffe. We used to have a tape of David Attenborough (of all people) keeping a straight face for an hour as he described the bizarre wildlife of the Sheba Islands archipelago in a documentary from April 1, 1975, but I can’t find any audio or transcript on the internet. If anyone finds it, let me know.

Meanwhile, as I’ve been writing about gold, you could always listen to Golden Slumbers by the Beatles, or New Gold Dream by Simple Minds (a great album whose title track was playing on the radio the first time I drove across the Golden Gate bridge), or Gold Mother by James, a much-underestimated album, in my opinion.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.