Kimberly could tell something unusual was going on as soon as she saw her clients on the computer screen. The man had been one of her clients for some time, after originally being referred by his father. The father, it happens, had been divorced late in life. The dissolution of the marriage, which had lasted for more than 40 years, was very traumatic for his children (including Kimberly’s client) and their spouses, putting aside the fact that it greatly complicated the financial planning. It didn’t take long for the other shoe to drop: “Another woman is living with Dad,” said Kimberly’s client. “We thought everything would smooth out when we moved him into the retirement center, but now this other woman is in his life—and his apartment—and we don’t know what to do.”

Cathy faced a different type of problem case. Two of her longtime clients were divorcing, and there was a wide disparity in the exes’ income that was bound to become contentious. The couple’s children were still of college age, which meant that after the assets were separated, the two would still face ongoing student expenses—thus ongoing arguments and resentment.

As a financial advisor, Cathy found herself caught among the parents, friends and siblings of the couple, all of whom felt the need to offer unsolicited opinions about how the situation should be handled. To make matters even more complex, both of the ex-spouses entered new relationships, which meant the circle of participants—and opinions—expanded further, adding to the dysfunction. The ex-spouses waited until after their sons graduated from college before moving in with their new partners full time.

The situation seemed all too normal for the boys. Many of their friends had experienced similar situations.

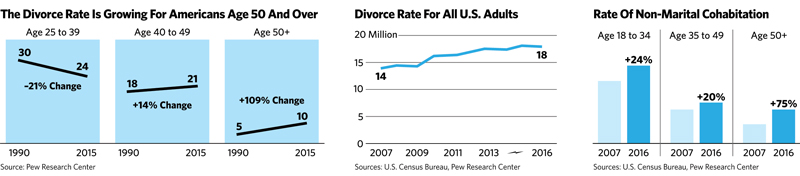

In fact, these predicaments are not unusual—and they’re growing more common every year. So-called “gray divorce”—the dissolution of marriages by partners in their 50s or older, usually after more than 30 years of marriage—is increasing at a faster rate than divorces in other demographics. U.S. Census data shows that while the divorce rate is actually becoming less common for younger Americans, the rate among those age 50 and older has doubled since the 1990s.

And frequently, older people who are widowed or divorced are living unmarried with new partners. The rate of non-marital cohabitation in this group has risen 75% since 2007.

This all raises real-life questions, awaiting answers that few people seem to have. An older parent’s new living arrangements can create ripple effects that involve estate planning, healthcare, financial planning, family dynamics and a host of other considerations. There are suddenly new questions and decisions to be made, not only for these “repartnered” older people, but also for their children, grandchildren and close family friends. The older children are likely especially concerned, since they’re the ones already taking care of aging parents, and the presence of a new companion in their mother’s or father’s life can add a whole new set of considerations and uncertainties.

Older people have a real need for companionship, and that has to be balanced with the expectations and emotional needs of the younger generations. The many complicated transitions involved in such situations—emotional, financial, medical, etc.—require careful handling that affords to all parties respect, fairness and, above all, love.

Understanding The Money/Relationship Ecosystem

It is often helpful to begin such conversations by putting finances and family relationships into perspective. We need to remember that money need not control or alter any of our most important relationships. We should be in control of the way money affects our families, and one important key to that control is open, honest communication about financial matters. In fact, it is often the case that money dominates the family dynamic most in families that never discuss it.

After the commitment to open and honest communication, a second important principle is for family members to focus on gratitude for what others have given them emotionally and financially. When everyone comes to the table thankful for what they have, rather than afraid or defensive about what might be taken away, the discussions tend to proceed much more smoothly and with fewer hurt feelings when it’s time to talk about the financial planning later.

Money And Marriage

According to studies, married people tend to have more money than non-married people. At the same time, money (or the lack thereof) can strain a marriage, especially a household mired in excess consumer debt. So it makes sense that researchers have also found higher rates of happiness among couples who show thrift in their household budgeting.