Kimberly could tell something unusual was going on as soon as she saw her clients on the computer screen. The man had been one of her clients for some time, after originally being referred by his father. The father, it happens, had been divorced late in life. The dissolution of the marriage, which had lasted for more than 40 years, was very traumatic for his children (including Kimberly’s client) and their spouses, putting aside the fact that it greatly complicated the financial planning. It didn’t take long for the other shoe to drop: “Another woman is living with Dad,” said Kimberly’s client. “We thought everything would smooth out when we moved him into the retirement center, but now this other woman is in his life—and his apartment—and we don’t know what to do.”

Cathy faced a different type of problem case. Two of her longtime clients were divorcing, and there was a wide disparity in the exes’ income that was bound to become contentious. The couple’s children were still of college age, which meant that after the assets were separated, the two would still face ongoing student expenses—thus ongoing arguments and resentment.

As a financial advisor, Cathy found herself caught among the parents, friends and siblings of the couple, all of whom felt the need to offer unsolicited opinions about how the situation should be handled. To make matters even more complex, both of the ex-spouses entered new relationships, which meant the circle of participants—and opinions—expanded further, adding to the dysfunction. The ex-spouses waited until after their sons graduated from college before moving in with their new partners full time.

The situation seemed all too normal for the boys. Many of their friends had experienced similar situations.

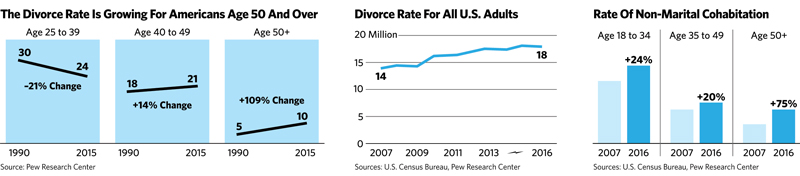

In fact, these predicaments are not unusual—and they’re growing more common every year. So-called “gray divorce”—the dissolution of marriages by partners in their 50s or older, usually after more than 30 years of marriage—is increasing at a faster rate than divorces in other demographics. U.S. Census data shows that while the divorce rate is actually becoming less common for younger Americans, the rate among those age 50 and older has doubled since the 1990s.

And frequently, older people who are widowed or divorced are living unmarried with new partners. The rate of non-marital cohabitation in this group has risen 75% since 2007.

This all raises real-life questions, awaiting answers that few people seem to have. An older parent’s new living arrangements can create ripple effects that involve estate planning, healthcare, financial planning, family dynamics and a host of other considerations. There are suddenly new questions and decisions to be made, not only for these “repartnered” older people, but also for their children, grandchildren and close family friends. The older children are likely especially concerned, since they’re the ones already taking care of aging parents, and the presence of a new companion in their mother’s or father’s life can add a whole new set of considerations and uncertainties.

Older people have a real need for companionship, and that has to be balanced with the expectations and emotional needs of the younger generations. The many complicated transitions involved in such situations—emotional, financial, medical, etc.—require careful handling that affords to all parties respect, fairness and, above all, love.

Understanding The Money/Relationship Ecosystem

It is often helpful to begin such conversations by putting finances and family relationships into perspective. We need to remember that money need not control or alter any of our most important relationships. We should be in control of the way money affects our families, and one important key to that control is open, honest communication about financial matters. In fact, it is often the case that money dominates the family dynamic most in families that never discuss it.

After the commitment to open and honest communication, a second important principle is for family members to focus on gratitude for what others have given them emotionally and financially. When everyone comes to the table thankful for what they have, rather than afraid or defensive about what might be taken away, the discussions tend to proceed much more smoothly and with fewer hurt feelings when it’s time to talk about the financial planning later.

Money And Marriage

According to studies, married people tend to have more money than non-married people. At the same time, money (or the lack thereof) can strain a marriage, especially a household mired in excess consumer debt. So it makes sense that researchers have also found higher rates of happiness among couples who show thrift in their household budgeting.

Different Lenses

At the same time, it’s important to remember that different family members—and especially those from different generations—tend to view money and its proper uses through different lenses. One spouse may be a dedicated saver, while the other gets an actual hit to the pleasure centers of the brain from making a purchase. When financial discussions are necessary, keeping these different perspectives in mind and maintaining respect for all points of view can lead to more productive conversations and decisions. But it’s key to have open, honest and respectful communication among all parties.

The Gray Divorce/Cohabitation Conundrum

Baby boomers are the largest generation in American society, and they’re entering the retirement ranks at an increasing rate (not to mention moving in together unmarried at a faster rate than people in other age groups). This is happening at a time when eldercare, with all its attendant healthcare, social, financial and emotional challenges, is becoming a concern for them and their Gen X and millennial children.

There are several factors at play when older people decide to live together without getting married or remarried.

Social Security. Older women who remarry typically lose spousal benefits that contribute an important source of their monthly income. Also, unmarried couples may pay less federal income tax on Social Security benefits than those who file joint returns.

Financial aid for their children. For persons with college-age children, the greater combined household income in a marriage may reduce the financial aid available to their kids at college.

Estate planning. People who want to pass assets to their children or grandchildren may find their inheritance plans complicated if they have a new spouse.

Alimony. People who remarry can lose alimony payments from an ex if they live in non-community property states.

Medical expenses. Having a spouse means you take on responsibility for someone else’s medical expenses. Unmarried couples may have more options.

There are emotional, financial and legal drawbacks to living arrangements among unmarried people. For one thing, it’s uncertain whether the relationships will last or how they might affect other family members, especially how new situations will affect the rights of financial beneficiaries. When it comes to legal status, in most states, marriage laws supersede cohabitation agreements when it comes to the disposition of estate assets, tort claims and other legal remedies.

Older People In New Relationships

When older people enter new relationships, they’ll need to understand what goals and values they share with their new partners and how the relationship will affect others. It’s also important for them to be able to share their differing attitudes toward financial matters openly and without judgment.

Beyond that, there are some important practical questions they’ll have to answer.

• Are their wills up to date? Especially when it comes to any language about the exes?

• How would they like to divide assets among themselves and their children or other heirs?

• What is their new partner’s tax filing status?

• Does their new partner have life insurance or retirement accounts, and who are the beneficiaries? What about the pensions?

• Who is the healthcare proxy? How involved do they want their new partner to be in their healthcare decisions?

• Who will be their primary caregiver if they become incapacitated?

• Who holds their power of attorney?

• Is their new partner currently receiving Social Security benefits from an ex-spouse? Alimony?

Cohabitants should also consider having a formal “living together” agreement. These can afford important protections to partners who aren’t married, since in most states non-marital unions do not enjoy the “defaults” provided by marriage. These agreements can provide guidance for matters such as:

• Who pays for what, and how much?

• What is separate property and what is commingled?

• How should commingled property be distributed if the relationship ends?

Though these may sound like plans for a worst-case scenario, these agreements should be approached with an attitude of joy for the relationship, concern for the rights of both parties, and respect for everyone involved. These plans should clarify what is being agreed to, how the agreement will be put into action, the functioning of mutual accountability, and the desired outcome of a successful relationship.

Important Considerations For Family Members

Like it or not, other people have vital stakes in these new relationships. The children, grandchildren and other family members must deal constructively with their own attitudes about the new arrangement, even if there are misgivings, uncertainty, financial or emotional worries for the welfare of the older parent or other considerations.

But family members should also keep in mind what is most important to the aging parent. After all, human beings never grow too old to desire companionship and the comfort of a close relationship, and the new person in their lives shouldn’t threaten the relationships older people have with their children. The kids and relatives should be “curious, not furious.” The more they can put themselves in their parents’ place and remain open-minded and considerate, the more likely they’ll continue to enjoy a trusting, loving and respectful relationship with their moms and dads.

But it’s important for adult children of aging parents in new relationships to take several things into account:

• They must think about their loved one’s long-term-care expenses, preferences, resources and options.

• They must plan for their parents’ ongoing money management.

• They have to think about selling or keeping the family home.

• They have to account for estate planning documents like trusts and wills.

• They have to make final arrangements, anticipating what happens when their parents pass on.

The key for the children is to be as involved as their parent wants them to be, while remaining as diligent as they need to be. The kids have the right to express their concerns, but they also have to be willing to acknowledge their parents’ choices and needs.

And, of course, there are a few things that the adult children of repartnering parents should definitely not do:

• They should not launch an intervention or open communications that feel like interventions.

• They should not involve unnecessary parties (for example, they shouldn’t discuss “Dad’s new girlfriend” at the Thanksgiving table).

• They should always aim to listen more than they talk. It’s no good if they fail to listen half the time.

• They should not focus on finances more than they do on people.

Instead, there are three elements that should guide every conversation:

1. Shared values. (“We matter to each other because …”)

2. Communication. (Family members should build bridges, not walls.)

3. Agreement on financial policies. (Parents and children should map the desired route to the parents’ financial destination together.)

Conclusion

Some things can be expected to remain constant: the human desire and need for companionship, the bonds between parents and children, and the mutual caring that families and loved ones provide for each other. Those things could become more complicated now that we’re living longer lives.

Financial advisors have to take all these financial and emotional aspects of aging into consideration. Our guidance should be informed by a thorough understanding of not just the financial implications of our older clients’ situations, but also knowledge of their priorities, goals and core values.

In these situations, as in most circumstances of life, relationships are paramount.

Kimberly Foss, CFP, CPWA, is the founder and president of Empyrion Wealth Management. Catherine Seeber, CFP, CeFT, is a vice president and financial advisor with CAPTRUST. Foss and Seeber will discuss the subject of divorce at this year's Invest In Women conference on November 10-11.