All kinds of great things are afoot. Bitcoin is at another all-time high as it continues to head for the moon. The Dow Jones Industrial Average hit a record, while many more useful indexes of American stocks came close to peaks. Breakevens for inflation over the next five years reached their highest in 16 years.

From that list, you would think that growth is on, risk is on and everything is awesome (barring some nerves that inflation is going a little too far). But that’s not how things are. There are any number of discordant notes as growth dwindles in the U.S., inflation in Europe rises to the kind of level that might force the European Central Bank to action—and, most importantly, China appears to be lapsing into its most significant economic slowdown not driven by pandemic disease in a generation. So it’s time for a panoply of charts working out what is going on in the world’s second-biggest economy, and how much it matters to everyone else.

First of all, note that there’s plenty to worry about in China. When people fret about it, they mean one of:

• Slowing economic growth;

• The credit overhang and potential for crisis in real estate thanks to the stricken developer China Evergrande Group;

• China’s problematic relationship with the West and the potential for another “Cold War”;

• Trade and the risk of deeper protectionism;

• The leadership’s distinctly authoritarian clampdown on the private sector under Xi Jinping.

This is quite a laundry list, and the items tend to link with each other. It’s as well to try to keep them separate.

Slowing Growth

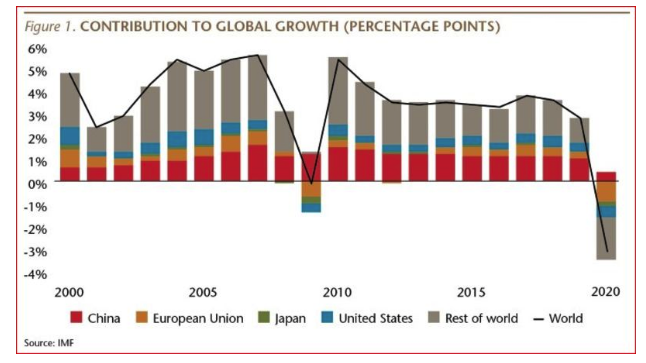

To start with, as everyone knows, China’s growth is special. Since 2001, the country has accounted for more of the increase in global GDP than either the U.S. or the EU every year. It’s been the world’s grower, and spender, of last resort. It even expanded last year. This chart of IMF data, produced by Andy Rothman, chief investment strategist of Matthews Asia, shows just how important China is:

Thus you would think that the plethora of economic data released at the beginning of this week would have caused more than a ripple in financial markets. To start with the one bright spot, exports have resumed their rise after several years of being becalmed. But this may be more a transitory sign of weakness elsewhere than a reason for optimism about China—heavy retail spending in the U.S. may have driven the gain, while China may also have benefited from shortages and supply chain problems for competitors.

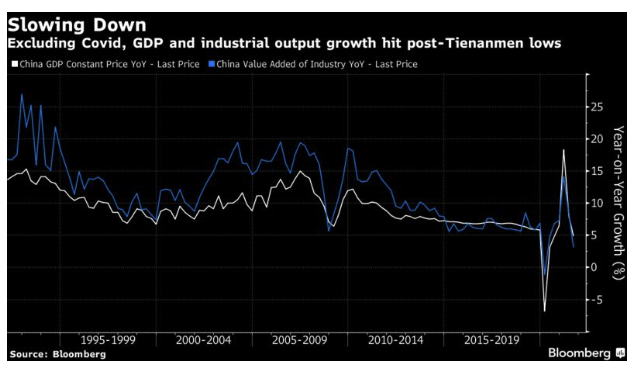

However, growth numbers for GDP and industrial production came in at their lowest levels in three decades. Both dipped below 5% for the first time in the post-Tiananmen era, save only for the brief recession forced by last year’s Covid shutdown:

If we look at annualized two-year changes, to try to get around the base effects created by the Covid shutdown, the pattern of declining growth grows clearer, for both the consumer and manufacturing sectors. This chart from BCA Research Inc. shows two-year annualized growth in retail sales and industrial production:

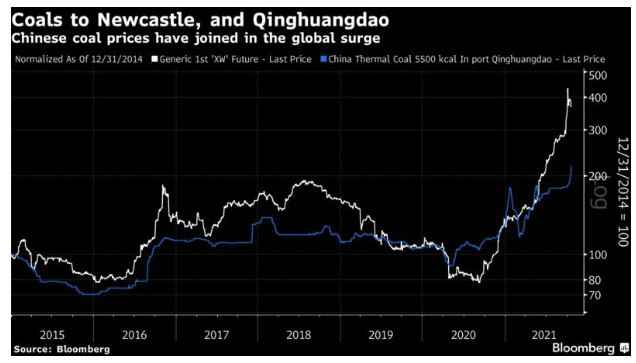

Why is this happening? It looks as though China’s fuel crisis, which saw power outages last month, has much to do with it. The price that businesses must pay for coal hasn’t risen as dramatically as in western Europe, but it has still more than doubled since early last year:

A recurrence of Covid shutdowns has also weighed. There are thus some reasons to believe that growth can pick up again. This might help to explain why the Chinese data didn’t spark a “risk-off” reaction in American and European markets this week; it also suggests that a dose of such sentiment could still lie ahead if growth doesn’t turn around.

Money Supply

If there is a reason to believe that growth won’t return to the kind of 6%-plus rate to which the rest of the world has become accustomed, it lies in monetary policy. The People’s Bank of China controls many levers over money supply and this has risen dramatically over the years, as might be expected to enable China’s phenomenal growth.

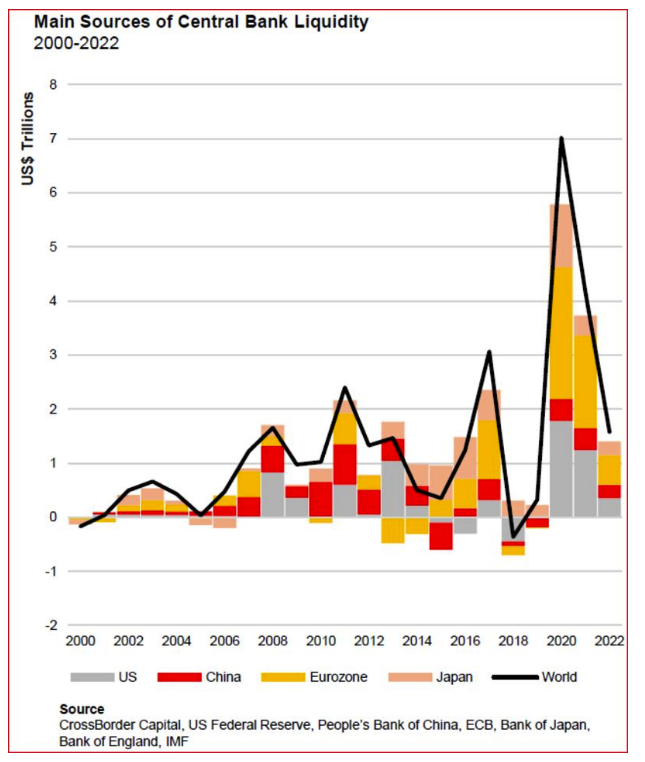

After the financial crisis in 2008, the PBOC in many ways came to the planet’s rescue by engineering a massive spurt of liquidity, while U.S. money supply was constricted. For the decade since, the rest of the world has been plagued by concerns that this debt overhang will lead to a Lehman-style crisis. The PBOC has been prepared to release liquidity when trouble threatens, as during the devaluation crisis of 2015, and last year during the pandemic. But policy makers are plainly anxious to rein in credit, and show no great desire to stimulate the country’s way out of the current slowdown. For the first time in a quarter-century, the supply of money is growing much faster in the U.S. than in China:

Accepting a slower rate of growth in return for reducing the risk of a credit crisis may well be sensible policy for China, but it will have effects elsewhere. The following chart from CrossBorder Capital Ltd. of London breaks down the world’s main sources of central bank liquidity since 2000. The PBOC played a vital and consistent role in the years before and after the crisis. It is now stepping back. The likely reduction in the amount of central bank liquidity over the next two years is on the face of it a reason to brace for slower growth, and for the risk of accidents as debt around the world grows harder to refinance:

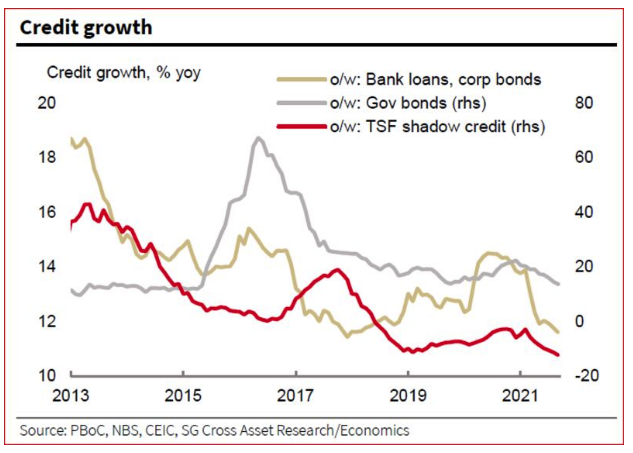

Looking across the different credit channels in China, this chart from Wei Yao of Societe Generale SA shows that all are tightening:

With evidence of slackening economic growth, this looks like an unduly Spartan approach. Several economists suggest that the PBOC will be forced to ease policy before the end of the year. As it stands, liquidity is tightening and likely to tighten further.

Credit And Real Estate

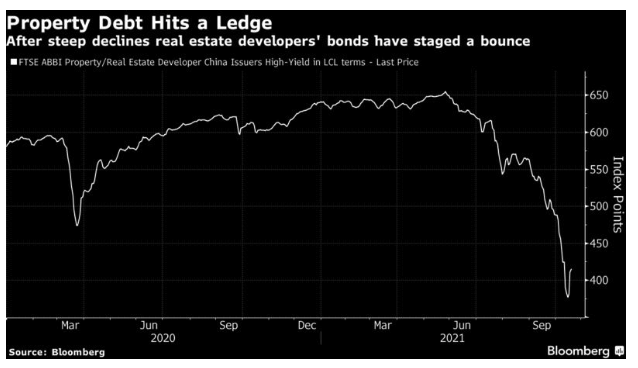

The main reason the Chinese authorities might want to rein in credit lies in its over-indebted property sector. This is why the travails of China Evergrande have attracted international attention. Its problems meeting payments sparked a dramatic selloff of high-yield bonds issued by developers, suggesting that the entire sector was thought to be in danger of going the same way. They staged a small bounce this week that has calmed nerves outside China, although for the moment it looks like one of the “dead cat” variety:

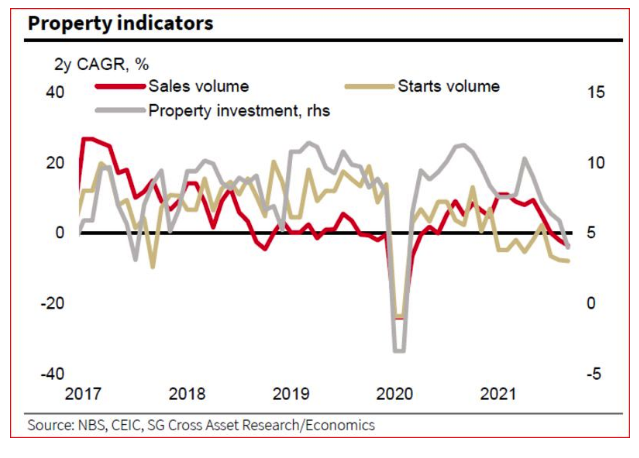

The intent, plainly, is to slow the property sector, and squeeze out speculative excesses. As with money supply, this is probably good policy, but likely means a reduction in the previously insatiable Chinese appetite for industrial materials used in construction. As this chart from SocGen’s Yao shows, the property sector is unambiguously slowing—and again, to avoid base effects, this chart is on a two-year annualized basis:

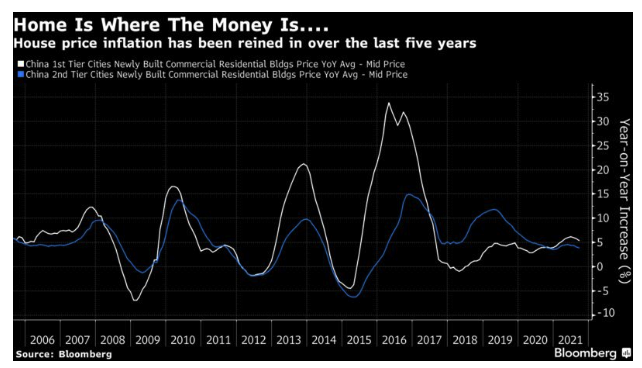

This can also be seen in the decline in house price inflation, which went ballistic at times during the last decade while also falling outright in some years:

So far, the signs are that Evergrande hasn’t triggered a Lehman-style implosion. The risk remains that an enforced slowdown for Chinese real estate has a more insidious effect on global growth.

Stock Markets

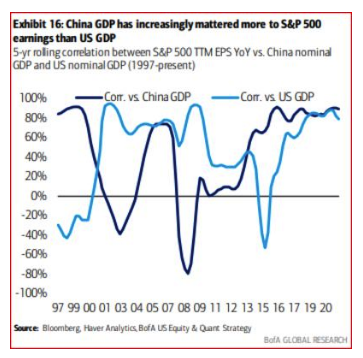

What effect will all of this have on global stock markets? On the face of it, a China that will accept growth of less than 5% is a very big deal. In recent years, BofA Securities Inc. shows that the S&P 500 was more closely correlated with Chinese GDP growth than with the pace of expansion in the U.S.:

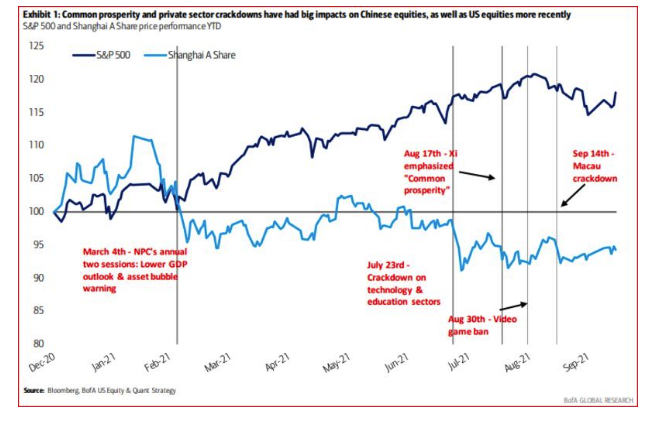

So far, the Chinese slowdown has had little impact on American animal spirits. Beyond that, the impact is complicated because there are so many strands to follow. BofA provides this handy chronology:

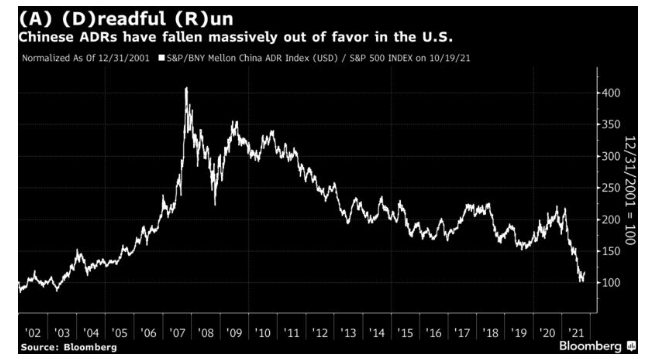

The succession of increasingly anti-capitalist moves by the Xi administration had clear negative impacts on stocks in China, but few had any great impact back in the States. However, if we look at the performance of Chinese American depositary receipts, or ADRs, covering larger companies, the way they have fallen from grace in the last few months is dramatic. Being based in China is plainly now seen as a disadvantage, after years of being viewed as a benefit for which investors would pay for a premium:

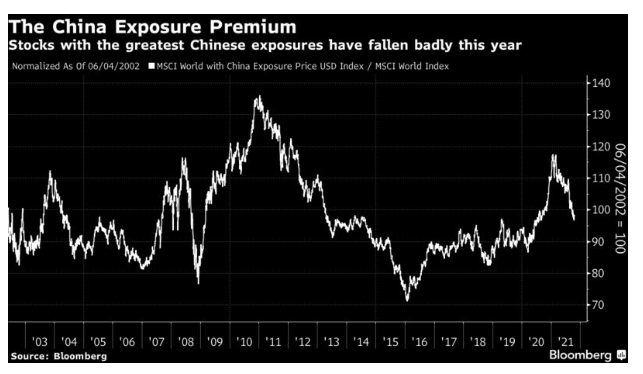

The performance of the 50 stocks within the MSCI World index with the greatest exposure to mainland China yields a similar result. Economic exposure to the country went even further out of favor around the 2015 devaluation, but this year’s fall has been dramatic. It’s hard to explain it as anything other than a response to the political clampdown. China’s governance and political risks now look much higher:

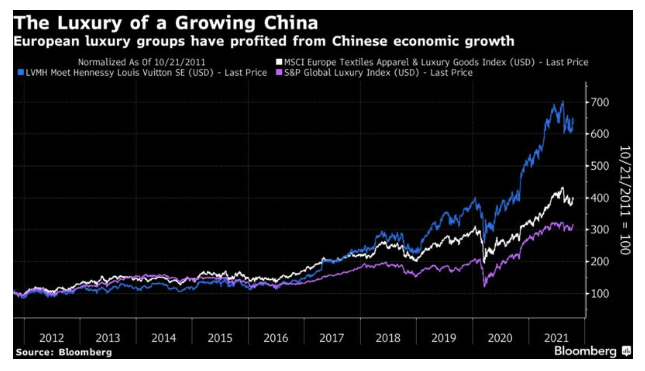

If there is any single sector that stands to be affected, it is luxury goods makers. Paced by the extraordinary success of LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE, luxury goods makers have had a great few years:

A Chinese slowdown might slow demand for luxury goods. If that’s the case, these companies could have much further to fall.

How great are Chinese political risks? For more than a generation now, the country has continued to call itself communist while being unabashedly pragmatic, and allowing the profit motive to help achieve many aims. Rothman of Matthews Asia, a former U.S. diplomat in the country and a long-time bull on Chinese assets, makes the case that political risks are now overstated in his blog, which you can find here. He reads Xi’s “common prosperity" program as an attempt to avoid the polarization and inequality that have come to plague the West, rather than a return to ham-fisted Leninism. His main point is that China has come far too far on the back of entrepreneurship to turn back now:

This perspective is based on the uncertainties caused by the rapid and chaotic roll out of new regulations, rather than on the long-term objectives announced by leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Market-based reforms and the private sector have created the economic growth which has kept the CCP in power for far longer than most other one-party, authoritarian regimes. Reversing these reforms would destroy China’s economy, which would destroy popular support for the CCP. Why would Party leaders take what would clearly be a politically suicidal path?

There is sense to this, and China’s political risks look to have been well priced. But for the time being it will be difficult to spark much investment into China itself. The risk that isn’t yet priced, and looks harder to avoid, is that slowing Chinese growth will have negative effects in the West.

Meanwhile, In Cryptoland

Cryptocurrencies continue to shoot for the moon, propelled there, it would appear, by Tom Brady. The hype is deafening once more, thanks largely to the launch of an ETF that can give you crypto exposure without the trouble of buying a bitcoin. As a result, bitcoin is at another all-time high.

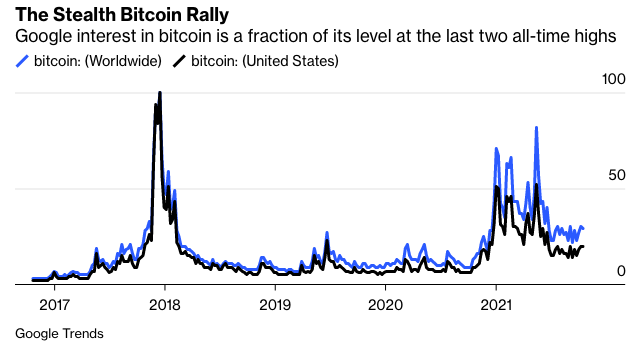

One thing is different about this craze. Among the public as a whole, it isn’t a mania, and the riches you can make in cryptocurrencies don’t dominate discussion in anything like the way they once did.

To demonstrate this, here are Google Trends searches for “bitcoin,” for the U.S. and the world. The lines are relative to their own high, and both peak in late 2017. The exercise shows that there is far less interest in bitcoin now than at that big top. The same goes for the cryptocurrency’s subsequent record rallies in late 2020 and the first months of 2021. Indeed, this all-time high scarcely seems to have prompted any attention:

It’s faintly possible that this tells us many of those likely to invest in bitcoin have already done so. A more likely scenario for now is that this rally has been dominated by institutions catching up with the phenomenon, rather than by retail buying. The effort to institutionalize bitcoin is underway; people in the real world are getting used to the notion of bitcoin and cryptocurrencies, and don’t feel so much need to jump on Google to research them.

Survival Tips

Working From Home still means occasionally Appearing On Television From Home. And that occasionally means that family spills over the airwaves. This discussion of the change of leadership at the Bundesbank from Bloomberg Surveillance this morning was a classic of the genre. Enjoy.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.