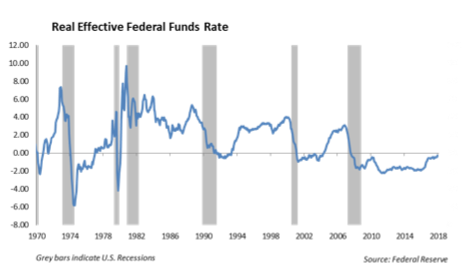

Historically, the Federal Reserve has targeted a real Fed Funds rate of 2 percent. However, in today’s new monetary regime, which includes managing the size of the Fed’s massive bond portfolio, we expect the Fed will be satisfied with a targeted 1.0 percent real Fed Funds rate. With the recent rate of inflation stubbornly below 2.0 percent, this would imply that the Fed has a targeted Fed Funds rate near 3.0 percent.

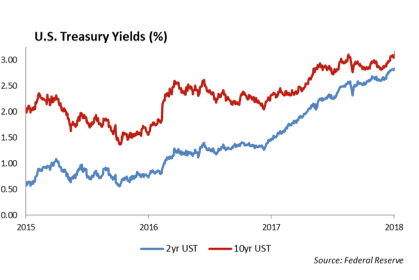

After a liberal monetary easing following the Financial Crisis, the Federal Reserve has increased short-term interest rates by 200 basis points over the last two years in a move to normalize interest rates. Now, investors are facing the issue: How high will interest rates rise? Since August, investors have seen the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note move from 2.82 percent to 3.20 percent as markets shift to a new paradigm that includes higher levels of interest rates.

The level of interest rates is critical to global capital markets because it sets the borrowing level with which borrowers and lenders can exchange credit. The lower the rate of interest, the more freely credit can transfer. In addition, lower interest rates accelerate the growth in private credit, which in turn, encourages private credit expansion.

In addition, the level of interest rates is used in valuations for public and private securities. Most financial models incorporate some discount rate to value future cash flows. This discount rate is normally derived as some level of risk premium over the risk free rate, which is determined from the current level of interest rates.

The New Monetary Policy Regime

Following the Financial Crisis, we have maintained that the United States has moved into a new monetary regime. History shows that monetary regimes last for an average of 30 years. We have moved away from a period where the Federal Reserve targeted short-term Fed Funds Rate through the management of our monetary aggregates (M2). This period lasted roughly from the early 1980’s to 2000 when the statutory requirement for reporting lapsed. Since 2008, the Federal Reserve has lowered the Federal Funds rate to zero and used its balance sheet to purchase bonds in the open market. This process of targeting measured bond purchases by the central bank, known as quantitative easing, resulted in the growth of the Fed’s balance sheet to $4.5 trillion. This program allowed the government to run deficits and the Fed to issue debt without the correlated run-up in the rate of inflation normally associated with monetary easing.

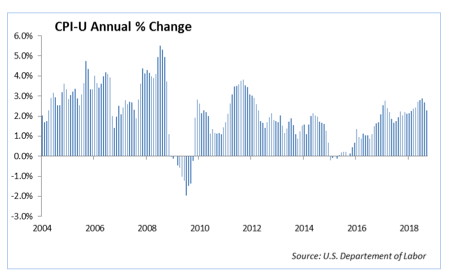

Over the past four years, the rate of inflation measured by the CPI-U has remained persistently low. As a result, with the nominal Fed Funds rate near zero over this period of time, the effective Fed Funds rate adjusted for the rate of inflation was actually negative.

Is there some level of real rate of interest that the Federal Reserve is targeting? We believe the answer is yes.

Typically, the real Fed Funds rate is declining sharply as economic activity is slowing. The exception was the recession in 1981-1982 where inflation was increasing as the economy slowed. Through the first half of 2019, we expect that the Fed will continue to push short-term interest rates higher. However, in the second half, we expect the economy to show signs of slowing, which will force the Fed to begin a narrative of “pausing” its tightening program.

Historically, the Fed has targeted a real Fed Funds rate near 2 percent. In this new monetary regime, however, we expect the Fed will only be able to push rates high enough to achieve a 1 percent real Fed Funds rate. As they attempt to shrink their bond portfolio during a time where the capital markets are adjusting to higher rates, we expect the potential negative impact on economic growth will cause the Fed to err on the side of a lower targeted nominal Fed Funds rate. With inflation near 2.0 percent today, this would imply a nominal Fed Funds rate closer to 3.0 percent, which leads us to believe that the Fed has roughly three more moves higher, including an increase of 25 bps in December.

Greg Hahn is president and chief investment officer of Winthrop Capital Management.