They say a horse made by committee is a camel, but in the independent broker-dealer (IBD) space, there are many ways to build the perfect beast—and with lots of client assets at stake and wealth to be transferred to a new generation, a lot of people with big pockets have decided this is the place to build it. Overall despite a stock market decline in the fourth quarter of 2018 that erased all of the year’s gains, broker-dealers had a good year.

The last 10 years have seen huge change in the IBD world: As the insurance industry and banks retreat, tired of the low margins and lost promises of bundling and cross-selling investment and annuity products, private equity has stepped up to seize opportunity. PE firms like Lightyear Capital, Genstar Capital, Warburg Pincus and Thomas H. Lee all have different agendas, and a more long-term view of what the space could be—whether it’s nurturing caterpillars into IPO butterflies, or tapping into different service channels for a variety of formerly bundled services that have been spun out of the insurance companies and banks.

To view FA's 2019 broker-dealer ranking, Click here .

To view FA's 2019 extended broker-dealer ranking, Click here.

“We’re certainly seeing consolidation in this industry and expect that will continue,” says Carolyn Clancy, an EVP and head of the broker-dealer segment at Fidelity Clearing & Custody Solutions. “Fidelity’s M&A transaction report found that the IBD channel had eight transactions in 2018, up from just three in 2017. But what’s more significant is the growth in assets involved with those transactions—it grew almost 175% year over year. Private equity is driving significant activity, as PE firms are holding a record amount of cash and see established, growth-oriented wealth management firms as strong investments.”

Meanwhile, regulators still cast a long shadow over the industry. The Department of Labor spent many years preparing a now-defunct rule ordering salespeople to disclose their conflicts, and though the rule died in court, state-level regulators are pushing similar initiatives and many financial institutions have already taken the spirit of the law to heart in their practices. “It appears to us that sellers [of broker-dealers] may be pricing in the perceived ‘risk’ of future regulation, but buyers are not,” says Amy Webber, the president and CEO of Cambridge Investment Group. “That is a positive for the sellers.”

If you don’t have size, however, you can’t command pricing from a technology and clearing perspective. Consumers have shifted to ETFs and index funds away from ’40 Act mutual funds whose admin fees, 12b-1 fees offered extra revenue for small broker-dealers. “Not only do they lose revenue from the 12b-1 fees, they also are losing revenue share from the mutual funds,” says Larry Roth, a veteran who in the past has run two big broker-dealers, both AIG’s Advisor Group and Cetera. “So the mutual fund companies and annuity companies and fixed annuity companies and others across the board are paying the little firms a lot less and in some cases nothing in terms of revenue share. If you’re a private company, it causes you to think about possibly selling.”

That’s just one factor speeding consolidation. Bigger firms are thus much better positioned because they can, in an age of margin compression, earn profits on things like technology, back-office and administrative fees, the overrides on the commissions and then spreads on cash in a higher interest rate environment. Roth calls it an arbitrage. “If I can make 20 cents on a dollar of revenue and the company that’s selling can only make 5 cents on a dollar of revenue, then it’s only natural that big firms are going to be buying those assets.” The big firms can have 10% to 16% of their revenue find its way to EBITDA, says Roth, now founder and managing partner at RLR Partners offering strategic consulting. Smaller firms now are seeing less than 5% of their top line making its way down to EBITDA, he says, and one of the reasons is operating expenses, which are dramatically less at big firms because of their scale.

What Do Private Equity People Want?

The private equity regime is different from that of insurers—private equity usually wants a three-to-five-times return on investments it holds for about five years to justify its leverage and the 2 and 20 fee structure. Their deals are often laden with debt.

Genstar, known as a growth-oriented private equity firm, entered the IBD world with a splash last summer, acquiring Cetera Financial Group for $1.75 billion, by far the biggest IBD deal ever. But Lightyear Capital’s Advisor Group, a network of four IBDs, capitalized on the trend of life insurers exiting the business. Last year, it acquired Signator Investors from John Hancock and earlier this year many reps at Questar Capital moved from Allianz Life Insurance to its insurance-oriented Woodbury unit. In a consolidating industry, IBD networks with different business models have an advantage. Signator was absorbed by Advisor Group’s Royal Alliance unit, and both operated on similar business models.

The multiple channel approach also motivated Morgan Stanley veteran Doug Ketterer to enter the business three years ago. Two years ago, he launched Atria Wealth, a holding company that’s acquired four firms, including Cadaret, Grant & Co. and Next Financial. The firm’s idea was that there are different channels with market share being overlooked “whether it be insurance, wirehouse, the bank channel and some of the other ones; what we really wanted to do is bring a differentiated approach to that channel,” he explains. “We have a presence in the financial institution group with CUSO and Sorrento Pacific—and they place advisory and wealth management investment solutions programmed in credit unions and banks. And then we have a different but somewhat similar channel in the traditional independent advisory channel with Cadaret Grant, which we acquired toward the end of [2018] with a pending acquisition of Next, which is similar in the traditional independent model.”

Financial Advisor reported earlier this year that Genstar and Lightyear had held talks about merging Advisor Group and Cetera. Melding the two IBD networks’ operations would have created a 15,000-advisor force to run up against giants like LPL and put the firm in great IPO stead. (By press time, that deal had fallen through.)

Tony Salewski, a Genstar partner and new board member, has declined comment about the talks. However, he said Genstar saw many overlooked strengths at Cetera. Those strengths include the way Cetera managed to hold together despite problems arising from its 2014 sale to Nicholas Schorsch’s RCS Capital and subsequent 2016 bankruptcy. “If it performs well through a storm, it will perform really well” now, Salewski explains. Cetera declined to participate in Financial Advisor’s Broker-Dealer survey.

The deals haven’t stopped. In late February, Warburg Pincus announced it had acquired a majority stake in Kestra Financial. No price was disclosed but sources said the transaction valued Kestra at about $700 million.

What Advisors Want

Then there are the advisors, who are making big demands on the broker-dealers they decide to dance with, including incentives, back-office help and technology—the kind of mobile apps that their new generation of clients are going to demand so they can sign on, invest and watch their money with ease. “Their clients are demanding it because the regulatory environment is actually increasing in complexity, so complexity can be simplified by technological solutions,” says Rich Steinmeier, head of business development at LPL. “They want us to make it easier to have an integrated proposal system that takes outside portfolios, analyzes them, makes a proposal and then integrates that proposal back into our advisory platform. So we made a purchase of AdvisoryWorld, a firm that has those capabilities.”

Advisor retention is critical. LPL grew last year as a result of its purchase of National Planning Holdings for $325 million. LPL was to pay more if it could hold on to 72% of the assets of NPH’s 3,200 advisors. In the end, however, LPL is believed to have captured about 70% of the assets, so it avoided the payment.

Still, the acquisition has provided a lift for LPL stock, which has surged from the high $40s in the summer of 2017 when the NPH deal was announced to $73 a share on March 11. Indeed, some think the transaction was a steal for LPL, given the prices Cetera and Kestra fetched, and that the subsequent surge in LPL’s stock price has fueled private equity interest in the IBD space.

Without the NPH additions, LPL filings suggest it had a small advisor loss for the year (it had 16,109 advisors according to its 10-K for fiscal 2018). One of the reasons is likely that the industry is fighting the impressive foe: age. Different sources put the average age of advisors in the mid-50s.

Like many firms, LPL helps its advisors buy other practices from those who are retiring, Steinmeier says, as a way to fight the aging exodus. “We’ve in the past year introduced an Independent Advisor Institute where we are standing with small business owners and advisors to help them introduce new talent that we are helping to train and grow into their practices so they can have transition solutions.”

Some firms are tackling the age issue head-on. Triad Advisors CEO Jeff Rosenthal believes his firm’s advisor force is about five years younger than the industry average. Triad is trying to drive a youth movement among both clients and reps. “Being entrepreneurial-minded, Gen X [clients] like working with business owners who happen to be financial advisors,” he says.

Raymond James, which has grown overall, said in SEC filings that its private client group’s fourth-quarter recruiting was muted by advisor retirements and advisors leaving the business. (The firm was still up to 7,815 total advisors at the end of 2018, an increase of 278 from the year before; that includes 4,649 independent contractors and 3,166 employee advisors.) Jodi Perry, the head of independent advisors at Raymond James, says the recruiting pipeline remains robust but says there’s another industry problem that might have a chilling effect on recruiting: “Some of the national [brokerage] firms are pulling out of the advisor protocol, so that’s changing the way the advisors are feeling about the current firms.”

Jodie Papike, a third-party recruiter at Cross-Search says up-front money or transition assistance from firms to get advisors to move has continued to creep up. There have been offers on the IBDs side that are as high as 40% of someone’s trailing-12-month gross dealer concessions “and can reach as high as 50%,” she says. “Five years ago, 40 was at the very, very top end, and an independent firm would typically never go higher than 40%. … That’s either 50% of their trailing-12 gross dealer concession or 50 basis points on their assets.”

All the consolidation creates recruiting opportunities. Securities America was believed to be the biggest beneficiary of attrition following the LPL-NPH deal. The Omaha, Neb.-based firm grew 26% in 2018, a year when the S&P 500 was down 4%. That all came from recruiting and the growth from existing advisors, Securities America CEO Jim Nagengast says.

He adds that NPH advisors who joined his firm managed to generate “98% of the previous year’s revenue.” Given all the disruption, Nagengast says the [industry] average is 80% in the year after switching firms but “we focused on the speed of transition.” Securities America has added 121 back-office employees over the last two years to support its growth.

Commonwealth has stuck to its recruitment knitting and doesn’t plan to grow through acquisitions but through its pitch to advisors with more assets who want to use its vaunted technology platform. The primary source of new recruits comes from IDBs and insurance-based broker-dealers, said Commonwealth managing principal John Rooney.

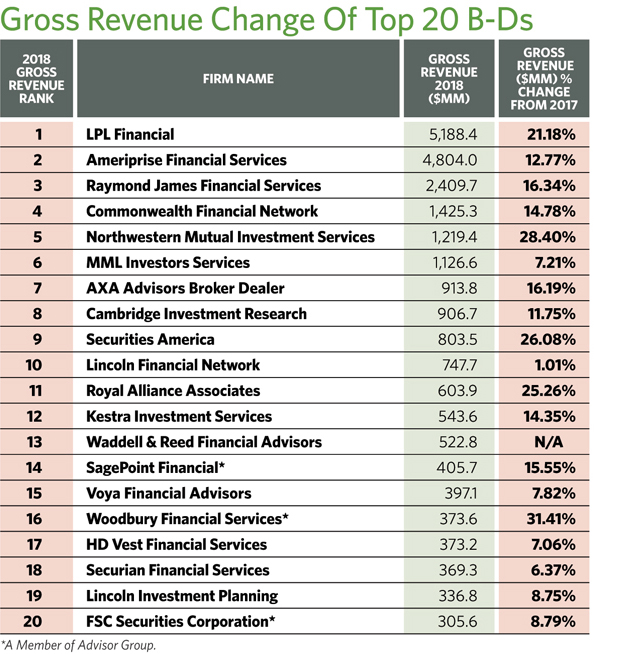

“Some businesses are forced to [acquire] when they’re challenged by recruiting,” says Trap Kloman, the company’s president and COO. “Or have less opportunities to grow. Our recruiting is excellent. We had a record year in 2018. We did $1.4 billion in revenue last year; divide that by 1,800 advisors [or about $775,000 per advisor]. … About $550,000 is our median.”

Is The RIA-Only Model The Future?

It’s also become increasingly important for the big players to offer their advisors an RIA-only option. That’s because the RIA space, along with retirement, is one of the biggest sources of attrition for IBDs.

Over the last year, most of the large IBDs have publicized their RIA-only custodian model widely, even if they’ve offered the option for a decade or more. For many younger advisors, the fee-only chassis has become the model of choice. Even though the DOL rule is dead for now, years of public discussion about fiduciary advice have accelerated this trend.

Another motivation is the opportunity to monetize one’s business, according to Derek Bruton, president of Chalice Wealth Partners, a fintech membership platform. Private equity firms are even more attracted to the RIA space, and dozens of aggregators are acquiring firms in it. “The valuations are quite different and the RIA side is valued much more favorably,” Bruton says.

The question for IBDs entering the space is whether to play offense or defense. Triad Advisors CEO Jeff Rosenthal, who is targeting younger advisors, has about 30 RIA-only advisors, and he maintains that offense is the way to go.

That’s what Commonwealth Financial Network is banking on. Today, Commonwealth has about 80 advisors in the fee-only space, but they tend to be eight to 10 years younger and have higher assets under management than the rest of the network’s reps, according to Greg Gohr, senior vice president of wealth management at the firm.

“We definitely anticipate marketing this to a certain segment of the RIA community,” typically firms with between $100 million and $400 million in AUM that have run into capacity and support issues, Gohr says. “We can give them everything they need to double their business.”

Bruton, who once headed up Merrill Lynch’s RIA-only operation, says playing defense—or setting up a business unit simply to slow attrition—doesn’t translate into a winning formula. “If you aren’t committed, your advisors and your staff will sniff it out,” he says.

It’s far too early to tell who the winners and losers will be, but Bruton believes that LPL and Raymond James Financial, both of which have been committed to this field for at least a decade, will be serious competitors.