The U.S. bond market took a day off to celebrate Christopher Columbus and Native Indigenous Americans, which was probably just as well. By the end of last week, the bond market was showing clear signs of losing its nerve over inflation again. Moreover, this wasn’t a uniquely American phenomenon: German inflation breakevens, the implicit inflation forecast that can be derived from the bond market, are at their highest in eight years, even if they remain below 2%. In the U.S., forecasts for both the next five years and the five years after that are close to the highs they touched during the brief inflation scare this spring:

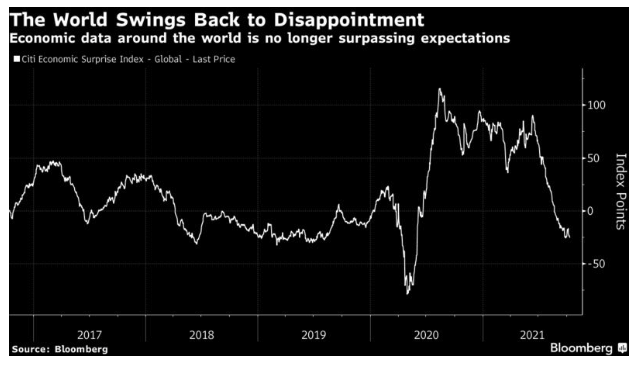

But even if there is some clarity that inflation is a problem again, it’s not because of any overheating. Incoming economic data for the world as a whole have generally been disappointing for the last few months, and on balance they are now inflicting negative surprises, as indicated by the Citi Global Surprise Index:

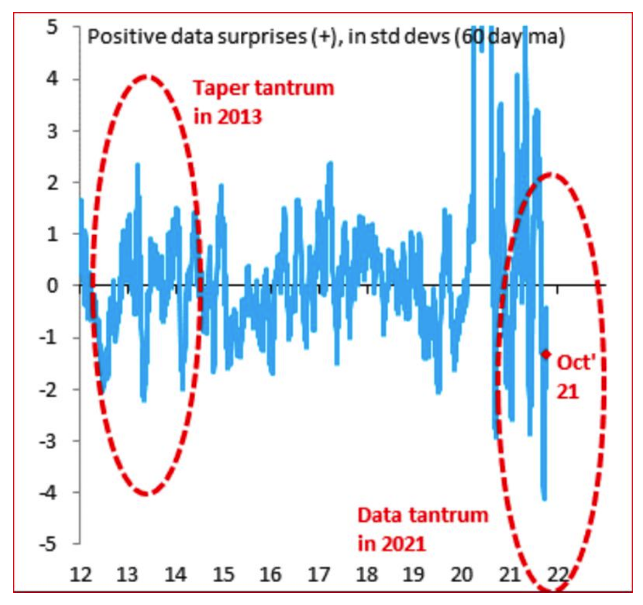

Meanwhile, in the U.S., Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance, notes data surprises are now running significantly negative. Importantly, they are notably more negative than in 2013, when bond yields surged in apprehension of tapering of quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve. “The big stylized fact of the last few months is that the recovery from Covid is way slower than markets had been expecting,” Brooks said.

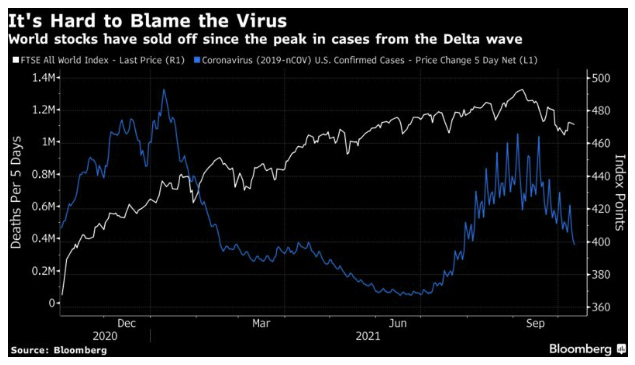

Note that he was talking about the economic recovery from the pandemic, not the medical one. After the successful vaccine tests in November 2020, almost a year ago, the stock market was able to look past the winter wave and ahead to the vaccination campaign, then began to pause with the onset of the summer delta wave in the U.S., still by far the most important economy. But in the last few weeks, the global stock market has sagged even as cases have reduced sharply:

Absent the arrival of a truly terrifying new variant that is lethal and also impervious to all the vaccines we have at present, it looks as though we have reached the point where the market is no longer that concerned about the pandemic’s medical progression. There is general optimism that it needn’t be as horrifically damaging in the future, along with pessimism that it’s bound to become endemic.

That raises the issue of just why bond yields are surging and the stock market is wobbling. Plainly the worry is that inflation is back, and it won’t be transitory. Handily, you can find the latest update of Bloomberg’s inflation indicators here. The bottom line is that inflationary pressure is indeed broadening, and this shows up most clearly in commodities markets, in the labor market, and in complaints from businesses that they are wrestling with higher prices.

There will plenty more inflation talk this week, with U.S. CPI data for September due on Wednesday. Here are the main points to watch:

Commodities

Energy prices are rising the world over, and this terrifies people. The echoes of the 1970s are obvious enough, even without the intrusion of Big Power politics as countries compete over resources.

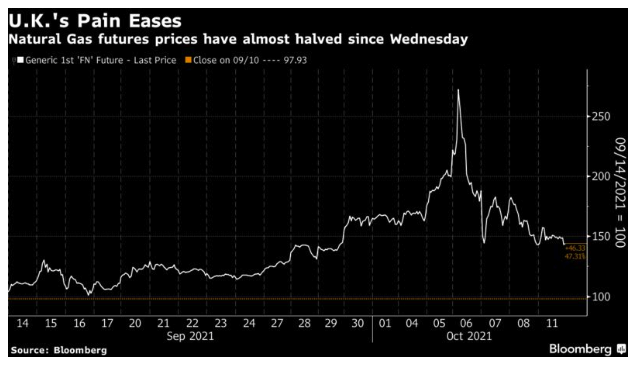

However, the most eye-catching crisis, in the U.K., has seen some easing of the pain in the last few days. The main natural gas futures contract for the U.K. has roughly halved since its peak last Wednesday. The fall seemed to start with a few words from Russian President Vladimir Putin about making more natural gas supplies available, which is alarming. But the fact remains that the most extreme energy scare to date has eased in intensity over the last few days:

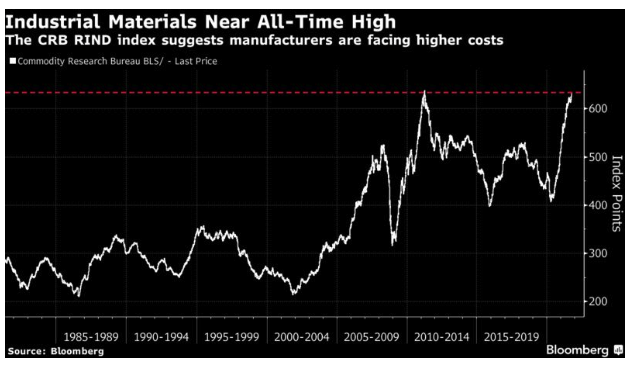

Beyond that, the oil market has plainly hoovered up the most attention. But other corners of the commodity market may be more concerning. The Commodities Research Board RIND index covers a group of industrial materials that are not available on futures markets, and so may better reflect the pure pressures on supply and demand into industry, rather than picking up speculative flows driven in other markets. It includes commodities such as burlap, tallow and lard. And this motley assortment of commodities is now almost at an all-time high:

The surge in prices is still not quite as great as the rise that brought it to the previous peak in 2011, just before commodities lapsed into a decade-long bear market. But the signs of pressure are unmistakable.

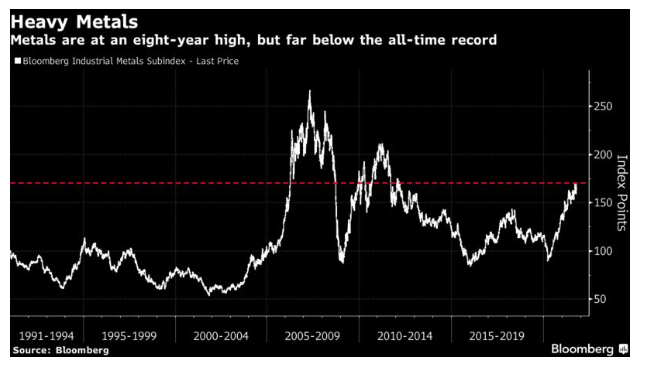

Then there is the move in industrial metals, which are normally driven by demand from China. At present, China is trying to douse speculation in metals, but that hasn’t stopped a surge in prices. Bloomberg’s industrial metals index is now at its highest since early 2012:

In the indicators, note that they are driven by levels, rather than percentage increases. This is on the theory that it is high absolute prices that create economic damage. Had we based the indicators on rates of increase, which is what many in the market tend to watch, the heat map would be implying much more inflationary pressure than it currently shows.

The Labor Market

The other factor raising inflation fears is the labor market. The non-farm payroll data, published last week, include figures on the rise in average hourly and weekly earnings. Despite the disappointing rise in payrolls, the data showed earnings continuing to rise healthily. In itself, this is a positive development that may yet alleviate much social tension. But it also implies inflationary pressure.

There are two problems with the data. One is the compositional effect. The most poorly paid workers tended to be laid off during the Covid shutdown last spring, with the result that the average earnings of those left shot up. A second issue concerns base effects. Comparing to 12 months ago risks a false comparison with an extreme low.

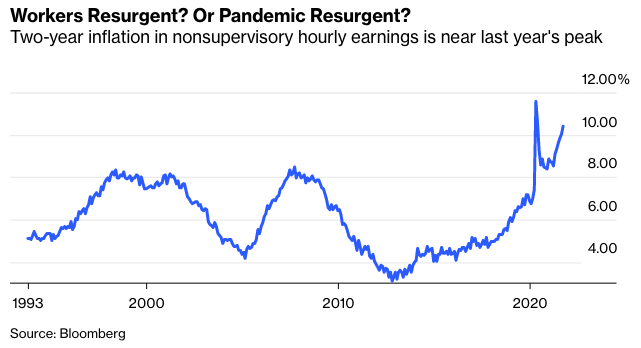

To try to deal with this very simply, I put together the following chart, which takes the two-year inflation rate (since September 2019, before the pandemic even started) of the average earnings for people in nonsupervisory positions. These will tend to be lower-paid workers. This is how the two-year increase in their pay has moved since 1993:

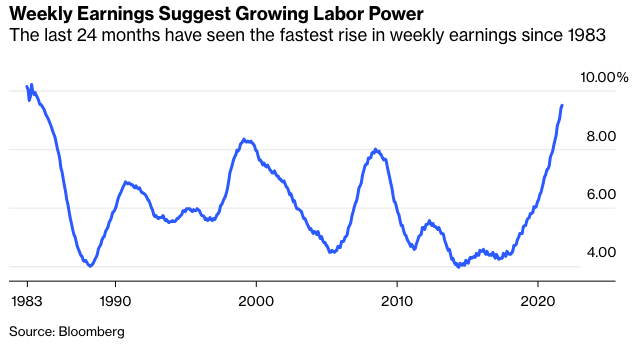

There are also data for weekly earnings, which can help spot when employers are keeping pay constant but cutting employees’ hours. This tends to be seasonal, so in the following chart, I’ve looked at the 24-month moving average of two-year inflation of average weekly earnings. The data go back to 1983, and since that year, on this basis, U.S. wage inflation has never been as high as it is now:

Many caveats apply. There may still be compositional effects distorting the numbers. The pandemic is still impacting the behavior of employers and employees alike. And more granular data (such as the wage tracker data due from the Atlanta Fed in the next few days) should give a much more accurate picture. Also, note that the levels of wage inflation showing up at present are not at all excessive, and only look high in comparison to a long period in which labor has had a very raw deal.

But at the margin, it is completely reasonable for numbers like this to awaken fears that inflation will be higher than the forecasts had been projecting.

The Corporate Sector

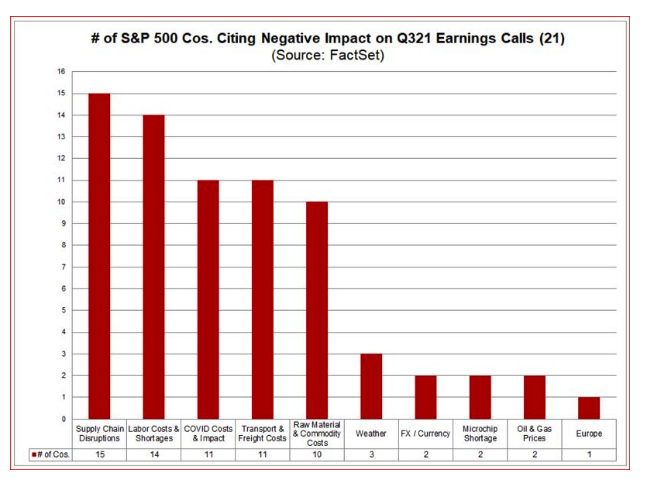

The earnings season for the third quarter is about to get underway, and it will inevitably provide much anecdotal information on how businesses are dealing with prices. Judging by the few companies to have reported already, many will take the opportunity to warn about supply shortages and rising prices. It’s possible that they will be doing this to excuse poor performance; after all, it’s a CEO’s job to put as good a gloss as possible on the results. But these numbers for the 21 S&P 500 companies to have reported so far, produced by John Butters of Factset, do show that bottlenecks and inflation are dominating discussion, and they are doing so more than a year after the worst shutdown conditions were lifted:

There are two reasons to take this seriously. First, note that only three CEOs complained about the weather, while more than three times that number complained about the costs of labor, transport and materials, as well as supply-chain disruptions. There has been plenty of extreme weather in the last few months, and it’s alarming that the inflationary conditions are so much more serious for companies than floods, fires and hurricanes are. Second, only two mentioned currency. The dollar appreciated by about 2% during the third quarter, and it’s up by 5.5%, on a broad trade-weighted basis, since it hit a low early in January. A rising dollar makes earnings generated in overseas countries appear to be worth less in dollars. The many multinationals in the S&P routinely complain about this. So again, we need to take them seriously when they complain far more virulently about costs created by the pandemic.

Survival Tips

One important tip to start off: When going on a brief transatlantic trip, make sure you have access to Wi-Fi at all points on your itinerary. Also, make sure it's strong and secure enough to handle remotely accessing a Bloomberg Terminal. I didn't do this when I went to England this past weekend for my cousin's wedding, with the result that I missed sending two issues of Points of Return. Sorry.

Some other hints borne from my weekend jaunt back home: First, if you do want to try traveling, it's more pleasant than it used to be. Providing you use the Verifly app to store all your Covid information, traffic flows very swiftly through calm and half-empty terminals. And, if you happen to need to go to Britain, be prepared to be gouged for ridiculous sums of money for your tests, one of which must be taken within two days of arrival, and the other within three days of departure (which in my case meant that I took two tests at the same time, and had to pay twice).

Finally, after a wonderful occasion I wouldn’t have missed for the world, here are some suggestions from the happy couple’s playlist for the reception. For their opening dance, they played the “Muppet Show” theme song, and it was great. As this was on the South Coast in Sussex, of course there was something by Brighton’s own Fatboy Slim: “Praise You.” And there was plenty of Madness, who still cannot fail to soothe the most furrowed brow. Everyone enjoyed “Baggy Trousers,” the soundtrack to the school years of the bride, groom and many of us in attendance. And their final dance was to “It Must Be Love,” the most beautiful song in Madness’s repertoire. I had forgotten that the video was set at a funeral. It was just as appropriate for a wedding.

(And have a wonderful life together, guys, from your big cousin…)

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.