In the first half of 2017, a record $10.15 billion worth of syndicated insurance-linked securities (ILS) were issued, according to Steve Evans, owner and editor-in-chief of Artemis.bm, a Brighton, U.K.-based news and data service focused on the securities. Overall, as of November 2017, the global ILS market was worth some $90 billion, he says.

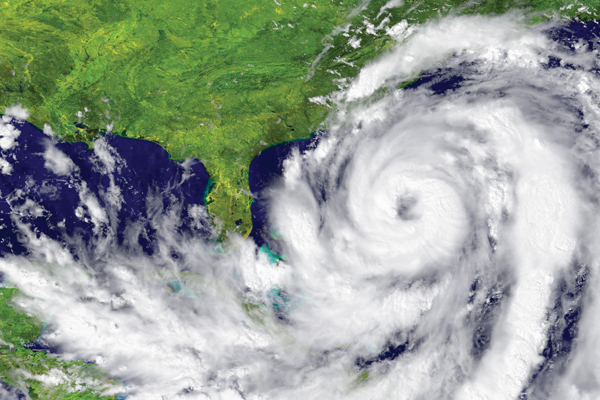

Much of this market is made up of catastrophe (or “cat”) bonds that see investors assume the risk of certain disasters such as hurricanes, playing the role of reinsurer. Generally classified as 144(a) private-placement securities regulated by the SEC, they can be traded only by qualified investors. But that’s only one piece of the pie. “Many transactions are now placed as collateralized reinsurance and then securitized privately for fund managers,” Evans says.

What exactly are these instruments? Where is this money coming from? And what should savvy advisors when they are considering the potential benefits and pitfalls of these vehicles?

What Exactly Are ILS Investments?

First, it should be understood that, as an asset class, insurance-linked securities comprise a range of alternative instruments accessible mostly to institutional investors. But Russell Hill, chairman and CEO of Halbert Hargrove Global Advisors in Long Beach, Calif., calls it a “quasi-institutional market.” He sees a fair amount of high-net-worth-individual participation.

“We have a pretty broad range of investors,” says Hill. “It’s a developing market, but the total market size is actually not large enough for some large institutional investors. Smaller institutions, many hedge funds and some RIAs use them, but in our case most of the people who own them are high-net-worth individuals.”

These securities represent a convergence of capital markets and the insurance industry. “Typically, when an underwriting insurance company decides it has too much risk in a particular area, it will sell part of that risk to a reinsurer,” explains Hill. The reinsurers, in turn, can raise capital and share a portion of that risk by issuing insurance-linked securities. “For them, this is capital that’s somewhere between straight debt and equity,” he says. “It comes from a different place on their balance sheets. So they want to issue it. They need the capital.”

And that need is growing, particularly in emerging markets, he says, where the insurance industry has developed along with the economies. “The more they develop, the more they insure. Then the reinsurance market has to take up that slack to help the local companies take that risk,” says Hill.

At the same time, bond investors are looking for yield in a low-interest-rate environment. Everyone gains, it seems.

Insurance-Linked Securities

January 2, 2018

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment