This summer, major world central banks are re-igniting their monetary accommodation. But one decade and billions of dollars, euros and yen of stimulus later, monetary policy seems almost exhausted. Instead, could fiscal easing kick-start growth and take us out of the low rate, low growth economic paradigm that we have been in since the 2007-08 financial crisis?

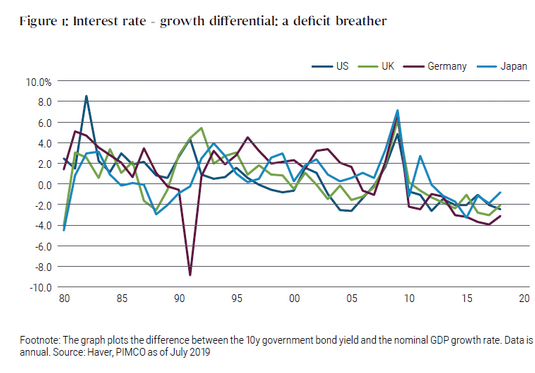

International support for fiscal easing is on the rise. The ascent of populist parties in recent years has brought increased support for fiscal easing, not only from populist leaders, but also from influential academics: Olivier Blanchard and Larry Summers, for instance, have stressed that debt is more affordable in the current low interest rate environment. As Figure 1 shows, sovereign yields are below nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates in most major developed economies, implying that governments can run primary deficits on a sustained basis without seeing sovereign debt/GDP ratios rise.

International policymakers, including former Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Ben Bernanke, current European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi and his soon-to-be successor Christine Lagarde, have also called for countries with fiscal space to spend more. And from a more extreme position, Modern Monetary Theory advocates promote looser fiscal policies, arguing that governments would never need to default on debt denominated in their own currency as they can always print more.

While most leaders and scholars agree that fiscal easing can be stimulative, the effects of fiscal policy depend on a number of factors. In this respect, we highlight three scenarios:

1. Effective: Standard economic theory says that expansionary fiscal policy increases output, inflates prices, boosts nominal and real policy rates, steepens the yield curve and supports risk assets. If this expansionary policy was concentrated in one country, say the U.S., the easing should strengthen the country’s currency, leading to increased imports and therefore, a deterioration in the country’s current account.

2. Ineffective: If the fiscal boost is perceived as temporary, and quickly reversed to restore equilibrium in public finances, any additional public spending could be met by increased savings by the private sector, in anticipation of future fiscal tightening. Economic activity and asset prices would largely be unaffected as a result. This would resemble a “Japan scenario,” given that Japan has failed to lift growth and inflation meaningfully over the past two decades despite multi-trillion yen fiscal deficits.

3. Loss of control: In this scenario, fiscal easing has adverse macroeconomic effects, as policymakers lose control of the system. Usually, profligate governments engage in fiscal easing financed by aggressive money printing. Institutional structures are not solid to start with, or become fragile in response of the loose policies, making markets and economic agents lose confidence in the institutional system. In consequence, inflation spikes, growth and risk assets sink, rates rise steeply and the currency depreciates. Some emerging markets have followed this route before.

Lessons From The Past

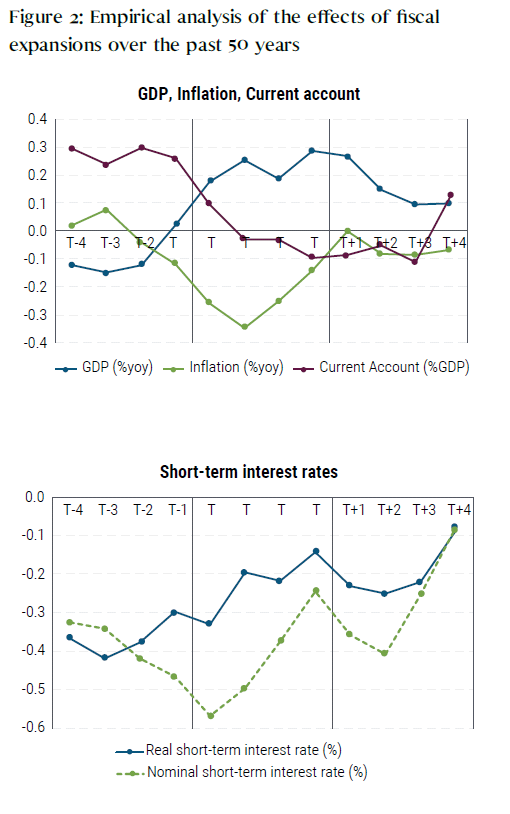

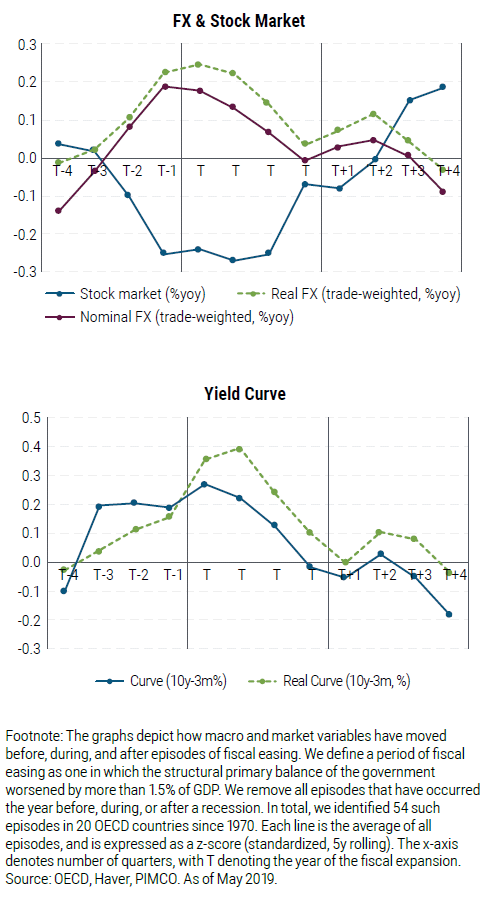

To test our scenarios, we identify 54 fiscal expansions in 20 different Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries since 1970, normalizing various macro and market variables to make them comparable.

As Figure 2 shows, we find that fiscal easing tends to push output and inflation higher (the latter with a bit of a lag), lift interest rates and strengthen the currency. Current accounts tend to deteriorate, while risk assets generally rally. Granted, these relationships are not perfect – and there may be on the forces in play during periods of fiscal easing – but the overall message seems to support conventional theory: fiscal easing does kick-start economies.

However, these effects tend to be short-lived. Following a fiscal boost, firms initially hire more people and increase production. But after a while, and as production approaches full capacity, firms start raising prices, ultimately bringing the economy back to where it originally started, just at a higher price level. If the central bank also raises its policy rate in response to the fiscal easing, in order to stem inflation, the short-term expansionary effects also end up being more muted. In this context, it is not surprising that the effects of U.S. President Trump’s tax cuts in 2018 waned soon.

How Likely Is This Regime Shift Towards More Aggressive Fiscal Policy?

While we see a more activist role for fiscal policy over the secular horizon, we are not banking on a regime shift that reduces the global savings glut enough to get us out of the New Normal’s L-shaped growth framework, globally. In a recent piece, for example, we have argued that U.S. interest rates could converge to or move below zero as the next economic downturn hits.

Still, increasing populist pressures, low borrowing rates, and limited monetary policy space and effectiveness mean that the chances of having a regime shift in the coming years is likely to rise. On a relative basis, the countries most likely to embrace this shift in our view are the English-speaking ones. Here’s our assessment region by region:

• US & UK: In terms of ability to handle a fiscal deficit, the UK’s budget deficit is at a 17-year low, giving politicians some wiggle room, while the U.S. can handle its rising debt/GDP ratio given the “safe-haven”, global demand for its Treasury notes. Both countries also have the support of their respective central banks, which provide significant anchors. In terms of willingness, and following Britain’s decision to leave the EU, most British political parties seem more open to fiscal expansion. In the U.S., meanwhile, a fiscal regime shift depends on the degree of institutional cohesiveness (President and Congress belonging to the same party) and on whether the government’s majority in Congress is sizeable enough. The bar for that to happen remains relatively high, which is why a fiscal regime shift in the U.S. is not our base case at present.

Europe: Fiscal easing has been constrained since the 1992-Maastricht treaty, and the countries that can actually afford to loosen up, such as Germany and Holland, appear less willing to so do. On the other hand, those most willing to spend, like Italy, are the least able. The Eurozone is also constrained because the ECB faces institutional and political constraints to buy national debt. In our baseline scenario, we therefore don’t expect a meaningful fiscal expansion in the Eurozone over the secular horizon.

• Japan: It is possible that fiscal policy turns more aggressive over the secular horizon. But given the lack of previous success, we think that such a move would be both less of a regime shift and probably less effective than in the U.S. Also, the very high starting debt level is already a constraint, while the VAT hike planned for later this year raises questions about the country’s willingness to embark on more fiscal easing.

What If The U.S. Goes Alone?

If meaningful fiscal easing ahead is concentrated in the U.S., we would expect the effects outlined above to be outsized for the U.S. economy relative to the rest of the world. In this scenario, the interest rate differential between the U.S. and the Eurozone could become more entrenched, the U.S. dollar would most likely strengthen and the country’s current account deficit widen (under former president Regan’s fiscal easing in the 1980s, the current account balance worsened by around 3% of GDP).

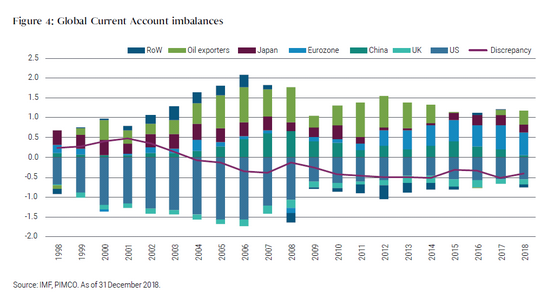

This could stall the improvement in global current account imbalances witnessed since the financial crisis, as seen in Figure 4: The U.S. has stepped up oil production, reducing energy imports and hence improving the country’s external deficit. The mirror image of that has been a fall in the surplus of the countries which exported oil to the U.S. What’s more, China has increased services imports (mostly tourism), reducing its longstanding surplus. Partly offsetting the overall global improvement in imbalances, the Eurozone’s surplus has increased, driven by a weak euro, a correction of current account deficits across the economically challenged periphery, and a sticky high surplus in export-driven Germany.

So, if the U.S. was to embark on a fiscal easing phase on its own, stronger domestic demand and in turn demand for imports would likely widen the country’s external deficit again, and worsen global current account imbalances. This would have several possible consequences:

• Fuel an increase in protectionism, and in turn lead to more global political risk.

• Lead to a less balanced global economy, where final demand engines are more concentrated. Capital flight risk could rise in the most levered economies, perhaps causing sudden stops in financing. Under this scenario, we could also not rule out risks of economic overheating, asset price bubbles and eventually significantly higher interest rates in these economies.

This is why we believe that a broad-based global fiscal expansion, rather than one led by a single country running an external deficit, would be preferable.

Investment Conclusions

As we argue in our Secular Outlook, remain positioned for a continuation of the L-shaped New Normal environment for the next few years, while exercising special caution given possible disruptions, including populism and a slowdown in China, among others.

These disruptive forces mean that a regime shift towards aggressive fiscal easing is more likely as time goes by, as governments seek to counter global economic challenges. We will closely monitor political developments in this regard, and be ready to adapt our strategies to a new scenario with higher growth, inflation and interest rates, were policy makers globally to turn on the fiscal taps.

Nicola Mai is a portfolio manager and a sovereign credit analyst for PIMCO. Peder Beck-Friis is a portfolio manager for PIMCO.