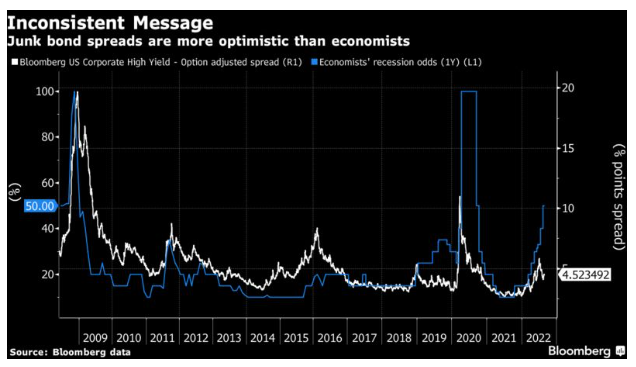

Corporate junk bonds in the U.S. are paying investors a paltry premium for the risk of holding them into a looming recession. Either spreads need to widen or the recession clouds need to vanish, but something’s got to give.

Consider the first possibility, the base case. Junk spreads typically track recession risk closely, and the economic gloom has been mounting consistently for the past nine months. In particular, the median economist in Bloomberg survey data projects a 50% chance of a recession in the next year, and indicators based on the yield curve keep warning of a downturn, too. Yet high-yield spreads are still sitting at 4.52 percentage points over the Treasury curve on an option-adjusted basis, in line with their average over the past decade, according to the Bloomberg U.S. Corporate High Yield index.

If you believe economists are right, then surely that spread will widen. Economists may have a lousy record at calling recessions, but that’s usually because they’re too conservative. They fail to foresee recessions or are too late but almost never forecast ones that don’t come to pass, as an IMF working paper found. In that sense, economists are at the the opposite end of the hysteria spectrum from equity markets, which get riled up about false signals all the time.

Of course, economists have good reasons to be concerned. The Federal Reserve is raising interest rates at a breakneck speed to fight the worst inflation in 40 years, and that process will entail some economic pain, a fact that Fed Chair Jerome Powell underscored in his annual speech Friday in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Resilient consumer spending and the strong labor market may mean that corporate and household debt ratios stay healthy for a few quarters, but the interest rate increases take 18 to 24 months to reach full effect, and the central bank clearly isn’t done raising yet. Meanwhile, China’s economy is slowing and Europe faces even greater recession odds than the U.S., augering headwinds from key trade partners.

But what if it truly is much ado about nothing and the proverbial “soft landing” does come to pass? Clearly, the market has to assign some probability to that outcome. So let’s take economists’ 50% recession probabilities and assume that there are equal odds of a non-recessionary bull case that narrows spreads back to around 325 basis points. On the flip side, let’s assume (optimistically) that the potential recession everyone’s so worried about wouldn’t be particularly deep and would send spreads to around 800 basis points. Under those assumptions, fair value is probably around 563 basis points, 1.11 percentage point above Friday’s close and near to the widest spreads of the year.

What can possibly explain away the disconnect? Part of it probably boils down to some version of the “there is no alternative” sentiment—TINA, as it’s known—that used to pervade equity markets. The downside risks are plentiful for the stock market, and commodities markets may have topped out after the early 2022 rally, so perhaps corporate bond risk doesn’t look so bad by comparison. As my Bloomberg Intelligence colleague Noel Hebert often reminds me, it would be unusual to lose money buying and holding the high-yield index with yields around 8%, provided you have a couple years to stay patient with it. On the other hand, perhaps spreads are just a final remnant of a vapid summer risk rally that’s slowly unraveling across asset classes.

Whatever the case, it’s unlikely that new investors will be lining up to finance high-yield companies anytime soon if markets are offering only 4.52 percentage points in spread for their trouble. One way or another, the status quo isn’t sustainable. In the medium term, that could mean anything from a spike in yields and default rates to the rare and coveted “soft landing,” but the least that bond traders could do is meet somewhere in the middle. For now, they’re still in fantasyland.

Jonathan Levin has worked as a Bloomberg journalist in Latin America and the U.S., covering finance, markets and M&A. Most recently, he has served as the company's Miami bureau chief. He is a CFA charterholder.