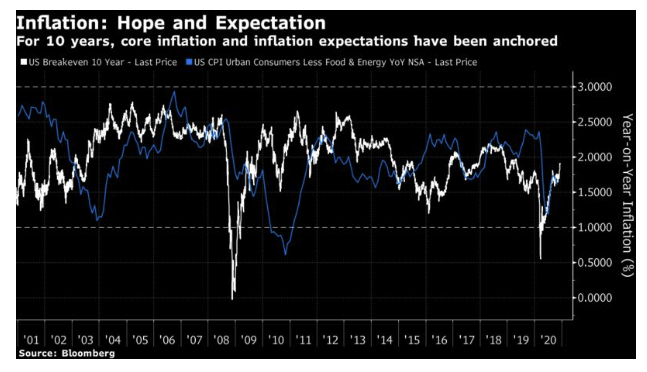

The U.S. publishes its last inflation data for the year on Thursday. The anticipation is that numbers will continue to be in line with the controlled outcomes to which the country has become accustomed. As this will be a column on the risks of a resurgence, it is important to start by making clear how utterly anchored inflation has been in this century. This chart shows how core inflation (excluding food and fuel) and 10-year expectations have varied over the last 20 years.

Neither has ever exceeded the Federal Reserve’s upper range target of 3%. Actual inflation dipped below the lower limit of 1% for a few months in 2010, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, while expectations briefly dropped below that level during the worst months of the global financial crisis and the Covid shock. Both times those deflationary shocks were over within weeks.

So, with the economy still struggling to find its legs, and the last wave of Covid likely to dampen economic activity for months to come, why would anyone worry about inflation? Here is the case.

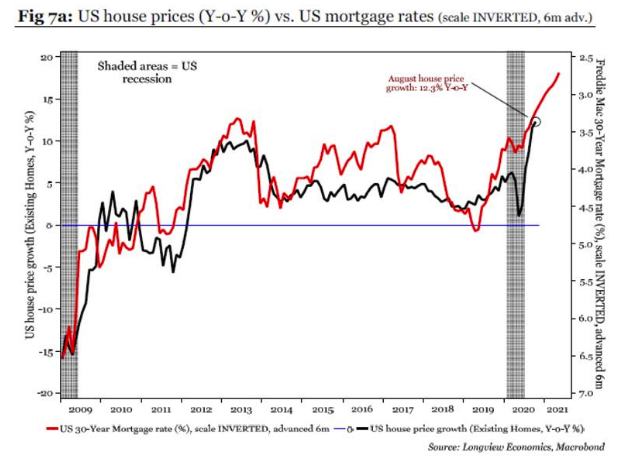

First, there is the housing market. It has roared back. Homebuilding companies are saying these are the best conditions in more than three decades (including, therefore, the bubble that blew up into the GFC). Their share prices are now above their pre-GFC peak, although this surge is plainly not as overdone as in 2005:

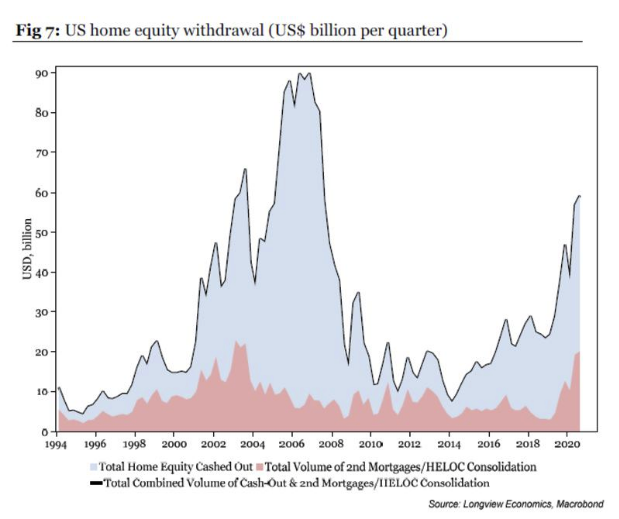

More ominously, people are starting to use their houses as ATMs again. This is what is happening to U.S. home equity withdrawal (in a chart from Chris Watling of London’s Longview Economics):

And there is every reason to think that the homebuilding boom can continue. As this chart from Watling shows, house prices tend to appreciate as mortgage rates fall — and mortgages are now very, very cheap:

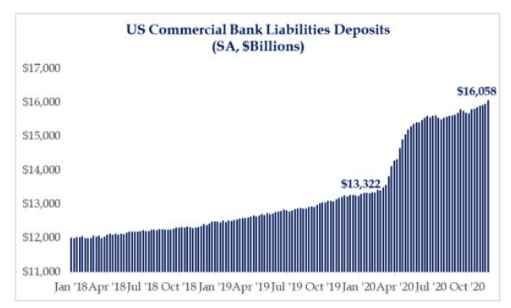

That implies there will soon be more money to be withdrawn from Americans’ brick-and-mortar ATMs. But it looks as though Americans don’t particularly need to go to the ATM, because the money they already have on deposit has shot up since the first lockdown. This chart is from Strategas Research Partners:

At this point many jaded readers will want to point out that there was a housing boom more than a decade ago, and it led to a deflationary crash, not inflation. There is a critical point of difference. When the property bubble burst, American households were painfully overloaded with debt. That has steadily been rectified over a decade of deleveraging, which, not coincidentally, was accompanied by disappointing growth. Now, household debt service ratios are at historic lows, as this chart from Watling shows:

Consumers are primed to spend money in a way they haven’t been for a generation. And the money is right at their fingertips. Monetarists would say that was the condition for inflation. After the privations of 2020, it is a safe bet that there is a lot of pent-up demand as well, so Keynesians should also brace for inflation.

If this seems unduly negative, to be clear, these numbers also suggest that the U.S. is ready for quite an economic boom. That should be something to enjoy, and might even go some way to leveling out the grotesque inequality that has built up over the decades of stable inflation. But some of the factors that have thwarted inflation in recent years are now absent.

Moving to the corporate sector, corporate treasurers also have plenty of cash on hand. Masses of it. As in twice as much as they have held on average over the last six decades, as shown in this Strategas chart, which uses Federal Reserve data:

Beyond the core measure, attention tends to be grabbed by headline inflation, which includes fuel and food and which, after all, represents the stuff that people actually have to spend money on. Next year could see a big change. For the post-GFC decade, oil prices have generally trended down. At any one point, gasoline prices have tended to be lower than they were a year earlier, neatly helping to reduce headline inflation.

While the oil market is still in a lot of trouble, and gasoline futures are still cheaper than they were 12 months ago, the chances are strong that that will change in the next few months. The base effects from this spring’s crash in oil prices should ensure that headline inflation starts to rise:

Then there is the matter of the dollar. It is weakening. The currency ended its last depreciation cycle during the GFC and has trended upward for much of the time since. This reduces inflation by making imports cheaper. A weakening dollar turns this around and becomes a pressure for inflation to rise.

So far, the world has avoided “cost-push” inflation arising from the bottlenecks and supply shocks created by the first phase of the pandemic. But there are still a few months to go, at best, and prices of a number of commodities are rising. For the longer term, if globalization doesn’t pick up again, that tends to mean companies must source their goods with more expensive suppliers, pushing up prices.

On top of all this, the Fed is now in the business of telling everyone that it wants inflation to get above 2% and stay there. The central bank is targeting average inflation, which means that it will happily tolerate gains above target for a while. When Fed Chair Jerome Powell unveiled that new policy at the Jackson Hole virtual symposium this summer, I had fun likening him to the drivers of Reliant Robin three-wheeler cars whose fondest wish was that their car could go fast enough to get them a speeding ticket. There is much slack in the labor market, minimal belief in inflation, and still little in the way of coordinated fiscal expansion, thanks to U.S. congressional gridlock. There is no reason to fear hyperinflation, or even anything on the scale of what was witnessed in the 1970s.

But it’s popular to expect a return to normality, and that would include a world in which economic expansions are accompanied by rising prices. Larry Hatheway and Alexander Friedman of Jackson Hole Economics, put the risks as follows. It is worth quoting them at length:

History suggests that inflation is typically slow to emerge. But when it does, it manifests inertia, as rising prices reinforce expectations of more to come. That’s why the Fed’s overshooting objective is risky. Once inflation exceeds thresholds, bringing it down could be difficult.

Which brings us… to the implications for asset prices. Rising inflation always undermines bond returns, with their fixed nominal coupons. But bond markets are much more vulnerable today, given significant over-valuation caused by central bank asset purchases and in the context of massive future supply due to unprecedented fiscal deficits. Bond markets will be in for a rude awakening if inflation accelerates.

Some argue that equities can withstand inflation because earnings and dividends rise with inflation. That’s simplistic and dangerous thinking.

As interest rates rise, so does the rate at which future earnings are discounted. Even more important, rising inflation increases economic risk. Central banks will eventually have to dampen spending to curb inflation. Accordingly, when inflation picks up investors require a higher risk premium to hold equities. Inflation de-rates valuations, which in some cases are already very high.

In sum, investors should care about rising inflation, which is now more probable than at any time in the past two decades. When it comes, it will be fast. Given that the consequences are huge for all investors, it is time to take notice.

ECB vs Covid

Thursday will see a dose of preordained excitement as the European Central Bank holds its last scheduled monetary policy meeting for the year. Christine Lagarde, its president, already promised that the bank will “recalibrate” its asset purchases at this meeting to deal with the developing challenges posed by the pandemic, so the only (very interesting) question is exactly what the ECB chooses to do.

The latest piece of high-frequency data is the ZEW survey of German industry, conducted early this month. This suggested that the current “lighter” lockdown is having the effects that might be predicted. Expectations for the future have improved slightly and are back close to their highs for the decade. The effect of rebounding Chinese demand for German autos, in particular, should be a boon. But the assessment of the current environment remains dreadful. The central bank will plainly want to do something to tide the euro zone through this period:

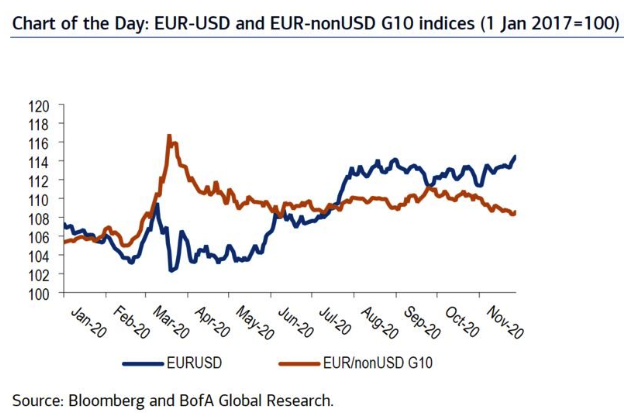

Whether Lagarde will also use this as an opportunity to push down the euro is another question. A weaker currency might help, but as the following chart from BofA Securities Inc. makes clear, the euro’s recent apparent strength is a function of the dollar’s feebleness. Against the rest of the G10 currencies, the euro spiked during the Covid shock, and is now sliding:

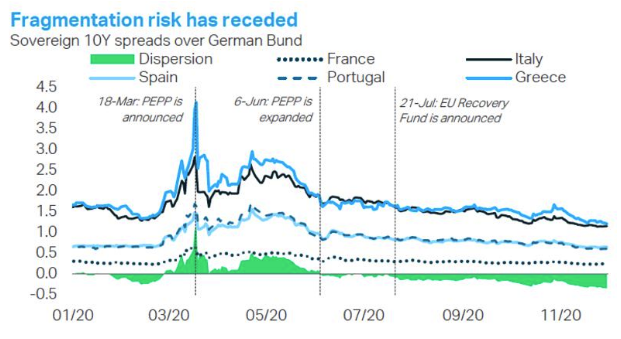

Lagarde also has a tricky political task on her hands. There has been great excitement this year over the EU Recovery Fund, in which leaders agreed after a marathon summit to borrow together to raise funds for Covid relief. There were distinct echoes of Alexander Hamilton’s masterstroke of collectivizing the states’ war debt and establishing the Treasury market, a critical step in moving the U.S. in a federal direction, and so this was hailed as a Hamilton moment. But as this chart from TS Lombard makes clear, the critical steps in bringing peripheral countries’ yield spreads under control all seem to have come from the ECB and its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, or PEPP:

As TS Lombard also shows, the PEPP has been skewed far more toward Italy and Spain than the predecessor APP, or Asset Purchase Programme. When it came to fighting Covid, this made sense. But continuing the PEPP will make the politics of the euro zone very complicated once more:

The key questions are the level of future purchases, along with Lagarde’s guidance on how long the PEPP will continue. This is TS Lombard’s handy graphic summary:

The ECB is likely to opt for something at the lower end of this range of possibilities. If Lagarde announces an intention to spend 27 billion euros ($33 billion) on PEPP per week until the middle of 2022, that will be very expansionary, and it will suggest that the more cautious “Bundesbank” voices have been overruled. It might also suggest that the central bankers are dubious about the hopes for joint fiscal policy. The dilemmas with which Covid confronts policymakers around the world aren’t over yet.

Survival Tips

Thursday night sees the beginning of Chanukkah, the eight-day-long Jewish holiday that celebrates the rebellion of the Maccabees. It’s a very sweet winter rite, in which Jews light an extra candle on the Menorah each night, and eat plenty of oily food to celebrate the miracle by which the oil in the lamp in the temple survived for eight days without running out.

If you want to know how to make latkes, the fried potato pancakes that go with Chanukkah meals, the Maccabeats (local heroes in my Upper Manhattan neighborhood), offer a Latke Recipe. After dinner, you are supposed to play dreidel, a game with spinning tops. This gives rise to the Dreidel Song, a song even more irritating than the average Christmas song, unless performed by the Maccabeats (listen to the whole thing to catch the Bohemian Rhapsody reference at the end). Chag sameach, everyone.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.