In a single day in early August, yields on $700 billion of global debt went into negative territory, raising the specter of negative interest rates in the U.S. Until this summer, most experts viewed negative rates as a problem confined to parts of the developed world challenged by slow growth and aging demographics.

By August 14, 10-year U.S. Treasurys were yielding 1.7%—a lower rate than 2-year Treasurys for the first time since 2007—and the 30-year long bond at 2.07% hit its all-time low. Incongruous as it might appears, there are real fears that an economy with a 3.7% unemployment rate and 7 million job openings was stalling out.

Even if America is one of the bright spots in the global economy, that’s little cause for celebration. Tens of millions of working-age Americans aren’t even looking for work. Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell’s misreading of the U.S. economy’s strength in 2018 was a major blunder, according to David Rosenberg, chief market strategist of Gluskin Sheff.

Many interpret the persistent low interest rates as the result of distorted monetary policy arising from the Great Recession, a failure that turned out to be punishing for savers and retirees. Other believe there are larger forces at work, especially declining population growth leading to economic stagnation on a global level.

Arguing that the prospect of negative rates in America was “no longer absurd,” Joachim Fels, global economic advisor at Pimco, cites other factors fueling the phenomenon—longevity and technology. “Rising life expectancy increases desired saving while new technologies are capital-saving and are becoming cheaper—thus reducing ex ante demand for investment. The resulting savings glut tends to push the ‘natural’ rate of interest lower and lower.”

Since the financial crisis, the U.S. savings rate has doubled to 8%. That means American consumers should be in a stronger position to deal with the next slowdown.

Changing Consumption Time Preferences

In recent years, financial advisors have witnessed many of their more affluent clients stand classical economic theory on its head. Traditionally, the time preference consumption theory held that people preferred today’s consumption over next year’s and thus had to be paid a higher interest rate if they were to be enticed to save. “It can be argued,” Fels writes, “that in affluent societies where people can expect to live ever longer and thus spend a significant amount of time in retirement, more and more people demonstrate negative time preference, meaning they value future consumption during their retirement more than today’s consumption.”

Nowhere is the reversal of traditional consumer time preferences more evident than among hard-working, high-earning individuals who are near retirement and inclined to use financial advisors. But it is also starting to surface among younger millennials captivated by the FIRE (“Financial Independence, Retire Early”) movement.

In nations where interest rates are negative for the entire 50-year yield curve, central bank policy has been accompanied by slow growth and aging demographics. Now that those countries are confronted with savings gluts, it’s no surprise their interest rates are anemic, though some have tried to spare small savers. Not only do Germany, Japan and Switzerland have older populations; they also have generous pension systems and very high savings rates. Fewer Europeans participate in the equity markets, but those who do can find higher dividends closer to home than Americans.

Some observers believe Europe’s situation is special. The level of interest rates there “is mind-boggling,” notes Loomis Sayles vice chairman Dan Fuss. “It has taken on a life of its own. The central bank is trying to hold the political union together and help the economy. Relative to the rest of the world, U.S. interest rates are high.”

Who would want to buy 10-year U.S Treasurys yielding a paltry 1.7%? European and Japanese investors, to name a few.

“U.S. Bonds are at their most attractive yields” compared with Europe’s in decades, says Robert Tipp, manager of PGIM’s Total Return Bond Fund. “That’s what people have difficulty getting their arms around.”

It’s also why U.S. government bonds staged such a powerful rally in August. “People who think Treasury yields are going to 3% or 5% are not looking at what’s going on in the world,” Tipp continues.

With America’s higher growth and younger demographics than other developed nations, its situation is slightly different. What’s not clear is how much those advantages will help if the global economy continues to slow. “The Fed has made it clear if we get hit by a sizable shock and [get] close to a recession, they’ll need to take interest rates down to near zero,” says Nathan Sheets, chief economist at PGIM Fixed Income and former Undersecretary of the Treasury for International Affairs in the Obama administration.

The sheer amount of global sovereign debt also acts as an economic depressant. It weighs on animal spirits, Sheets says, makes people worry and drives them into safe assets. When prices for risk-off assets like government bonds soar, institutions like pension funds with pre-established bogeys may feel compelled to move out on the risk curve as prudently as possible.

At the same time, Sheets notes that a number of structural factors holding down rates at both the long and short ends of the yield curve look strong and persistent. In the wake of the financial crisis, bank regulations around the world force them to hold safer assets.

The Fed is targeting 2% inflation. Yet in another sign of the economy’s softness, the central bank’s favorite price indicator, the personal consumption expenditure index (or PCE), has managed to hit that number only 10% of the time in the last decade. Still, inflation remains relatively stable in the U.S. while the rest of the developed world frets about deflation.

Demographics, Debt And Asset Prices

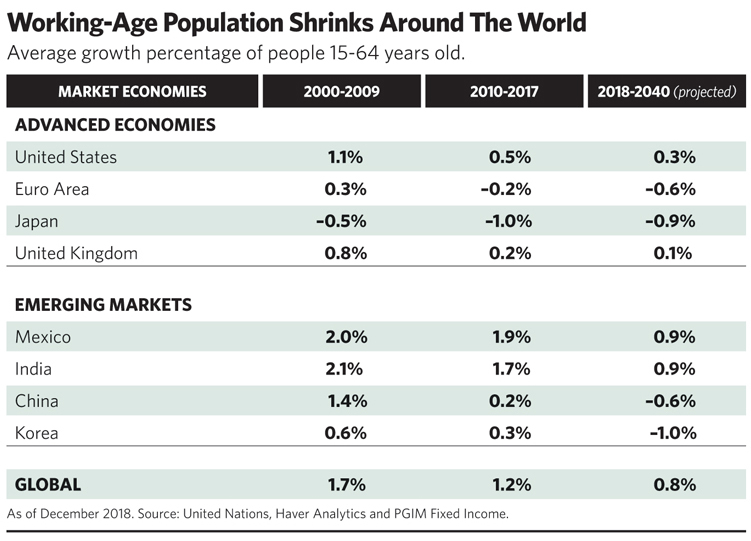

Over the next two decades, China’s working age population, 15- to 64-year-olds, is likely to shrink at 0.6%, exactly the same rate as the eurozone’s. “China is on course to replace Japan as the world’s largest nursing home,” observes economist and market strategist Ed Yardeni. America’s demographic picture is superior, since its fertility rate virtually equals its population replacement rate.

Still, the implications for the global economy are far-reaching. As longevity makes demographic profiles everywhere more geriatric, it puts pressure on governments “to borrow more and accumulate more debt to provide retirement support programs” for their rapidly expanding base of senior citizens, Yardeni says That can exert deleterious effects on traditional economic policy instruments like debt-financed government spending and tax cuts. In the 20th century, both were seen as stimulative for the economy. “That no longer seems to be the case,” Yardeni concludes.

At some point as people age out of the workforce, deteriorating demographics inevitably should collide with increased demand for spending on services for those same individuals. Tax revenues, unfortunately, are likely to be curtailed, Sheets projects. As younger workers watch government services “increasingly being skewed to the old,” upcoming generations might become a force for austerity.

What can prevent a clash of generations? Keeping older citizens in the workforce is one option. The Bureau of Labor Statistics expects the 65- to 74-year-old age group to be the fastest-growing in the next decade.

The longer people work, the less pressure they face to liquidate their lifetime wealth, easing downward pressure on asset prices. Sheets says extended career longevity is already occurring in the U.S. and Japan, though not in Europe.

When it comes to asset prices, older investors tend to become more risk-averse. Theoretically, this should contribute to lower yields.

Miniscule interest rates can also keep equity prices elevated, even if corporate profit growth is muted. Sheets contrasts the earnings yield on stocks (the price-to-earnings ratio reversed) with bond yields. If the S&P 500 is selling at 19 times, it translates into an earnings yield of about 5.2%. Since equities are a long-duration asset, the 10-year Treasury is the appropriate comparison. The difference between 5.2% and 1.7%, or 3.5%, is a proxy for the equity risk premium.

Whether that justifies today’s stock prices is anyone’s guess. What is clear is that smart minds don’t believe the recent drop in Treasury yields is an aberration. Rosenberg believes yields on the 10-year bond could fall below 1.0% “before all is said and done.” Tipp, the 2017 Morningstar bond fund manager of the year, believes they will fluctuate around 1.5%. That could make dividend-paying equities a reasonable alternative.