Expectations for inflation are breaking upward, as are stock markets. In the U.S., 10-year inflation expectations are their highest since 2014, at just above 2.2%. German inflation expectations are also rising sharply, but the gap between the two is now the widest it has been since the global financial crisis in 2008:

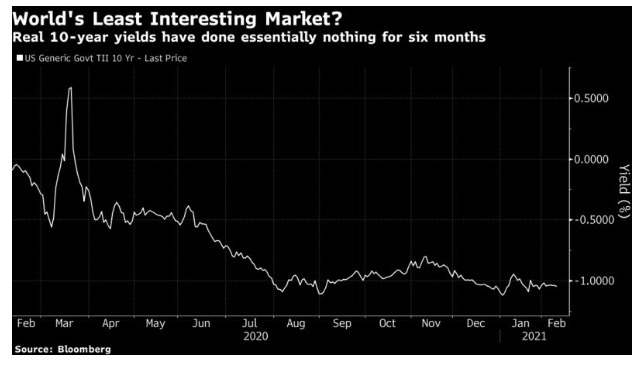

Rising inflation can be a problem, but it can also be a symptom of growth. The strength of the stock market suggests that investors are looking solely at the good side for now. And that, as ever, can be explained by the bond market, which continues to give equity investors room to operate. As Brian Chappatta notes elsewhere, the yield on the 30-year bond is now above the round number of 2%; but what really matters is the way that real yields, taking account of inflation, have moved. And they have barely moved at all. This is the yield on 10-year Treasury inflation-protected securities:

There has been a huge change in inflation expectations since last summer, and it has had no effect whatever on real yields. This allows stocks and alternative assets like bitcoin to flourish. The reason inflation-protected yields can stay stable is that investors are confident the Fed really will allow inflation to “run hot” — meaning that it will average above 2% for a while — and that inflation in turn won’t take off in a serious way to levels of or 4% or 5% or beyond. If that were to happen, the Fed would have to raise rates, and people buying bonds at current prices would lose a lot of money.

If the market is correct about this set of assumptions, then we have about as perfect a set of conditions for equities and risk assets in general as one could ask. Are they right?

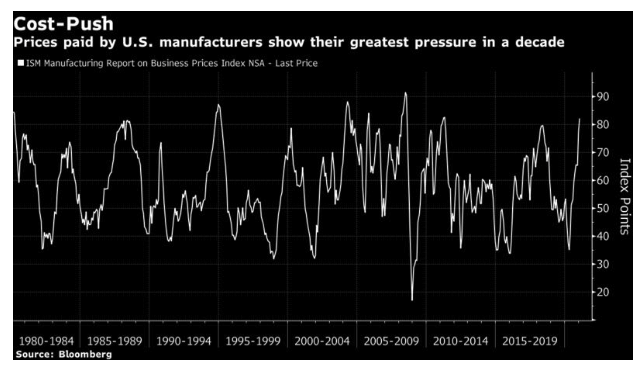

Recent macro numbers suggest that inflation pressures are worryingly high, even if they have not yet broken out. Prices paid by manufacturers, as measured by the ISM survey, are showing the greatest pressure in almost a decade:

Meanwhile, unit labor costs, measured quarterly, also suggest that labor is getting more expensive, in a way that hasn’t been seen in decades:

So is the market really right to be so confident that inflation will remain under control?

Handily, the next installment of the Bloomberg book club will be addressing the issue in a live blog on the terminal tomorrow at 4 p.m. London time/11 a.m. New York time. We will be discussing The Great Demographic Reversal by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan, which makes a long and persuasive argument that the market has it wrong, and inflation is due for a secular increase.

If you haven’t read it yet, you won’t have time to complete it, but it will still be worth following the discussion, which will involve Pradhan, along with me, my colleague Stephanie Flanders, and Barclays Plc’s chief U.S. economist Blerina Uruci. If you have time, try to pick up a copy and read just chapter five. That has the kernel of their argument that the current demographic shift, which is seeing the relative number of retirees and dependents increasing after several decades in which the world’s working age population steadily rose, will lead to higher inflation.

Their case is that with fewer workers, labor will have greater negotiating power. As the employed will have to pay more and more in taxes to look after the elderly, they will use that negotiating power to gain higher wages, which will lead to inflation.

The main reason others differ from the Goodhart and Pradhan thesis, I think, is that there is a belief that the retired won’t be allowed to become so expensive. Pension benefits will be trimmed back, the retirement age will rise, and the working generation will win a little back from the older generation, rather than having to take it from their employers through collective bargaining. If this happens, the effect of aging will be yet more disinflation, as the workforce continues to expand and everyone feels an even greater need to save.

Arguing against the Goodhart/Pradhan thesis is the intergenerational fury that is widespread at present, and obvious in the attempt by the Redditors who took part in the short squeeze of GameStop Corp. to get back at “boomers.” With good reason, millennials feel a simmering sense of injustice when they look at the luck of the baby boomers. This could lead to higher retirement ages and so on.

Arguing in favor of Goodhart and Pradhan is the extreme difficulty countries around the world have found when they have tried to reduce pension benefits. The recent sudden breakdown of social order in Chile was largely triggered by anger over inadequate pensions, for example. Last year, Emmanuel Macron in France tried and failed to raise retirement ages, giving up in the face of widespread protests.

Here is perhaps the crucial passage in the book:

If we are right in our political economy assumption that the social safety net will remain in place, then the age profile of consumption will continue to be flat or even upward sloping. The elderly will depend on (and vote for) government support and continue to save too little for the longer life they have inherited. The ineluctable conclusion is that tax rates on workers will have to rise markedly in order to generate transfers from workers to the elderly.

Workers, however, would not be helpless bystanders. Labour scarcity… will put them in a stronger bargaining position, reversing decades of stagnation… They will use that position to bargain for higher wages. This is a recipe for recrudescence of inflationary pressures.

The world is still not ready to think about the inflation that is likely to rise structurally. Central banks will, soon enough, have to revert to their normal behavior. The zero lower bound is largely consequences of a combination of a China effect, an unprecedented demographic backdrop and the deepest cyclical shocks since the Great Depression, once during the financial crisis and more recently during the pandemic.

Are they right? To follow as Pradhan defends this thesis, go to TLIV on the terminal on Wednesday. Send any questions beforehand or during the live blog by email to [email protected].

Mario To The Rescue

Maybe this is what Mario Draghi meant when he said he would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. Back in 2012, as a freshly installed chairman of the European Central Bank, Draghi’s promise finally convinced the markets that the euro zone could muddle through its sovereign debt crisis. By the time a populist Greek government attempted to call the European Union’s bluff, three years later, enough order had been restored that the EU could cow them into submission.

What was surprising was that the markets never attempted to call Draghi on his pledge. The chart below shows the spread of Italian over German 10-year bond yields, the clearest measure of the perceived extra political risk attached to Italy. The yellow line marks Draghi’s speech. Italian spreads have never since approached their level of the summer of 2012; as ECB chairman, Draghi was spared from having to show whether he was prepared to go through with his vow in the event of a speculative attack.

Now, however, it looks as though the debt is coming due. Italy’s last general election was in 2018, and resulted in a bizarre coalition between the left-populist Five Star Movement, and the right-populist Lega. That sent the spread over bunds flying higher, as one of the few things the two parties had in common was their anti-Europeanism. Now, after a botched confrontation with the EU over Italy’s budget deficit, the exit of the Lega from the coalition, and a dreadful pandemic, we are in the outlandish position where Giuseppe Conte, prime minister since 2018, has resigned, and the only person all parties seem to agree on as a new premier is Draghi. While he may be one of the most famous and internationally respected of living Italians, Draghi also happens to be one of the most strongly pro-European. He also happens not to be an elected politician.

Some thoughts on this. First, political science and particularly political institutions are more important to investing than many realize. What has just happened is the equivalent of President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris standing down because they can’t get their policies through, and the parties in Congress coming together to make Ben Bernanke president. In other words, this just couldn’t happen in the U.S. Whether that is a good or a bad thing, I leave up to you.

Is it good for Italy? The country has done this kind of thing before. The blue lines show the premiership of another Mario, Monti, who had previously been a European commissioner, and was called in to act as premier in the wake of the toppling of the populist Silvio Berlusconi. His appointment briefly calmed the markets; but he still needed Draghi’s intervention to vanquish the speculators, and his premiership was over within two years.

Draghi has the job of spending money that the country receives in Covid relief, rather than Monti’s miserable task of overseeing austerity. And his presence at the center of the EU sharply increases the chances that it can thrash out a way to make some kind of a common fiscal policy work. This will be seen as a sharp reduction in risk for the euro zone as a whole, and with some justification.

Investors might remind themselves, however, that Italy’s voters will get their say in 2023, if not before. Draghi might not be able to face them down as easily as he faced down the markets in 2012.

Survival Tips

You never know what music will raise your spirits. My daughter Andie has persuaded me to listen to the music of Hozier, the young Irish musician best known for his debut hit Take Me to Church, an angry attack on intolerance in general, and the Catholic church in particular. Some of his other songs, however raise a smile. My favorite is Jackie and Wilson; it’s infectious. For an explanation of the underlying philosophy, Hozier handily explains it here. Alternatively, there is Someone New, or Moment’s Silence, which sounds religious, and isn’t. He has a soulful and original voice and I’ve enjoyed listening to him.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.