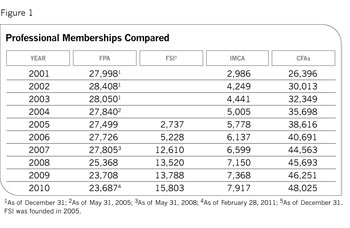

The Financial Planning Association has suffered a 15% loss in membership over the past five years while other professional membership organizations for financial advisors have grown rapidly. According to statistics from the FPA, membership over the past five years declined from 27,726 to 23,687-a sudden 15% drop after years of stability.

Though the association has endured membership declines before in past economic recessions, the recent drop has occurred while other competing organizations have seen their memberships grow sharply:

The Financial Services Institute, a group formed in 2004 after broker-dealers were jettisoned from the FPA, has increased its membership more than fivefold since the end of 2005, rising from 2,737 to 16,000.

At the Investment Management Consultants Association (IMCA), which represents investment consultants and recently started a designation for wealth managers, membership has risen nearly 40% over the past five years.

Advisors have suddenly become the fastest-growing segment of the CFA population and have reshaped the CFA Institute (CFAI) into a more advisor-centric organization. The number of CFAs in the U.S. has doubled in the last five years, and 29% of them now say they manage private client assets.

An examination of membership figures from the professional organizations serving advisors is instructive because it reflects the changing character of U.S. financial advisors and financial advice. (See Figure 1.)

The growing concentration of wealth in the U.S. and the hollowing out of the middle class has produced fewer opportunities for advisors serving the middle-market-individuals with less than $1 million of assets-a target for many financial planners and FPA members. Meanwhile, IMCA and CFAI designations and programs focus on high-net-worth individuals, a target market that is growing and presumably helping to make these organizations more popular with advisors.

While other membership organizations for advisors are prospering because of these secular trends in the economy, the FPA is being tested by multiple challenges.

Much of the loss in membership in recent years can be attributed to the FPA's advocacy on major industry positions that, at times, put it in direct opposition to many of its members.

The FPA's embrace of the Certified Financial Planner designation alienated non-CFPs, who in the past constituted a large percentage of its members.

The FPA's successful lawsuit against the Securities and Exchange Commission, which led to a ruling that ended the exemption of brokers from registering as an RIA, undoubtedly infuriated its members working at Wall Street brokerages as well as many independent registered reps.

In recent months, the FPA's advocacy for applying to registered reps the same fiduciary standard that now applies to registered investment advisors under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 again put it at odds with many registered reps and brokerages.

About 60% of the FPA's members are dually registered as RIAs and registered representatives, and many of them do not support applying the '40 Act fiduciary standard to advisory activities.

In addition, the FPA's members are aging and its ranks are not being filled by enough younger members to offset the slide. FPA membership is declining by about 50 members a month.

A factor accounting for the FPA's decline may have been its leadership's decision in 2003 to split off its broker-dealer division, established in 1987 by the IAFP. In doing so, the FPA set up what's now become a rival membership group, the FSI.

The creation of FSI is referred to by some in the industry as the FPA's "spin-off" of its broker-dealer division, but that's a misnomer. A spin-off implies that the FPA received something in exchange for splitting off this segment of the organization, similar to the way shareholders receive the pro rata value of shares in a new company when its parent spins off a line of business. As a 501(c) not-for-profit organization, however, the FPA received nothing in return for separating itself from B-Ds.

"I was in the room when it happened," says Dale Brown, now president and CEO of FSI. "I can tell you exactly what happened."

Brown was one of the principal players in the events leading up to the FPA's decision to split the B-Ds from the FPA. He had begun his career working at the International Association for Financial Planning in 1988 and served as the IAFP's director of government affairs. After the IAFP merger with the ICFP, Brown became the FPA's associate executive director.

"Not long after FPA was formed, it became clear that FPA's advocacy was focusing on advisory issues," says Brown. "Because FPA was created to advocate for financial planning, [the leaders] were reluctant to advocate for B-Ds because it could dilute their message to regulators about the uniqueness and value of financial planning."

In the months following the formation of the FPA in 2000, the tech bubble burst. Stocks would not bottom until 2002, but the mutual fund scandal headlines established new battle lines between B-Ds and many independent advisors, especially those not affiliated with a B-D. These were dark days for B-Ds, as regulators found them complicit in violations ranging from failing to reduce sales loads based on break points to undisclosed revenue-sharing schemes and other sales violations.

With the leadership of the FPA moving toward a professional model that today is manifested in its support of a strong fiduciary standard, it made less and less sense for them to share the podium with B-Ds. After all, the mutual fund and brokerage scandals were providing a marketing bonanza for CFPs unaffiliated with a broker-dealer.

Decisions at that time to make the FPA a planner-centric organization sowed the seeds for the current situation-the rise of the FSI and the weakening of the FPA. In fact, the same professional issues essentially define the two groups today and make them rivals.

The events of the time are well documented in a November 2003 article in Financial Advisor by Editor Evan Simonoff: "Financial planning," he wrote, "now is an emerging profession that has survived a violent bear market and an extended economic slowdown in remarkably good condition. Advisors may have watched their hair turn gray in recent years, but they have unquestionably gained market share."

Reflecting a prevailing sentiment of 2003, Simonoff added, "Many practitioners have businesses that are healthier than the brokerages and financial services companies that helped underwrite much of the profession's early growth."

The mutual fund scandals in 2002 and 2003 underscored the diverging interests of the FPA's B-D division and practitioners in the FPA's leadership. With successful practitioners who supported the professional movement in control of the FPA, the group asked B-Ds to leave in 2003. Though some B-D executives said they had been "jilted," the decision was based on divergent positions on advocacy issues. Simonoff reported: "FPA President David Yeske presented the decision as a fait accompli and said that it 'was born of integrity.'"

The B-Ds were invited to become "corporate members" of the FPA. Some B-D executives were miffed at how the separation was handled by the FPA, but neither side displayed outward animosity or rancor during the decade that followed.

No one at the time envisioned that the B-Ds would create a rival membership organization for registered representatives. Yet that's what happened. Moreover, FSI is throwing its weight behind FINRA to become the self-regulatory organization for RIAs who have more than $100 million under management and are regulated by the SEC. The FPA opposes FINRA as SRO.

The FSI has 126 B-D members with 188,000 registered reps, and 16,000 of those reps are FSI members now. Membership costs between $99 and $129 a year, and Brown says the group advocates for independent advisors affiliated with B-Ds.

The rise of the FSI is dividing the financial advisory business over the same ideological lines that existed in the 1970s and 1980s and separated the IAFP from the ICFP. In a way, it's almost like the merger of the two groups never happened.

Marv Tuttle, the CEO and executive director of the FPA in the years following the merger, describes the period from 2000 to 2008 as "an era of defining clarity of membership purpose clashing with the FPA's desire to position financial planning as a true and legitimate profession."

"Some members did not support our leadership positions," Tuttle adds.

"But I know our board continues to support the delivery of financial planning under an unambiguous and universal standard of care which meets the fiduciary test."

Tuttle says the average age of an FPA member is 55. "We're seeing an average of 50 to 60 members retire on a monthly basis," he says.

He says that decisions made over the next year by the SEC and Congress on the regulation of RIAs will be crucial to the FPA. "The conversations that will happen over the next six to 12 months will have an impact on us," he says.

"We think that coming up in a short bit, we will see a requirement to be a fiduciary and we want to be in a position to offer best practices to do that," he continues. "We recognize we're in this conundrum because we believe a fiduciary standard is coming. We have taken a position to get ahead of the curve for our members.

"We're just trying to remain true to our position that the [fiduciary] standard be at the level of the '40 Act."

Brown says FSI supports the fiduciary standard. "But we've also said that for there to be true harmonization, something has to be done about the woefully inadequate supervision and examination of investment advisors," Brown says.

"Reps of B-Ds are deciding to drop their B-D licenses and go RIA-only and escape the rigorous oversight-and yes, also the hassle-of FINRA and their B-D's compliance dept," Brown continues. "They're fleeing to a regulatory scheme where ongoing oversight is virtually nonexistent, and that's not good from a level-playing-field and competitiveness point of view, or good for investors. We think a fiduciary standard must be coupled with an effort to close that regulatory gap."

Brown says the best option for reform is an SRO governing RIAs, and "FINRA is the most appropriate candidate for that role."

While the SEC can enact rules to establish a new SRO for RIAs, Brown says the agency will not exercise that authority because it has been burned several times in recent years. Because of the SEC's "unfortunate record in court," Brown says the SEC is asking for explicit authority from Congress to make FINRA the new SRO for federally regulated investment advisors. "Unless Congress explicitly enacts legislation, the SEC won't give FINRA the authority," Brown says.

"The SEC is woefully underfunded and understaffed to do the job," he says, citing estimates that one-third of RIAs have never been examined. "Post-Madoff, how in the world can anyone say RIAs should be left to self-supervision?"

FSI is just one of the new membership organizations competing with the FPA for the attention of advisors. IMCA, a Washington D.C.-based group, is making a concerted push for new members and it has already been growing strongly in recent years.

In the ten years ended December 31, 2010, IMCA nearly tripled in size to 7,917 members, while the FPA membership dropped more than 15%. The IMCA membership has also grown amid the last three years of financial crisis and recession.

The IMCA, besides being a membership group, also licenses advisors in much the same way as the CFP Board does. About 80% of its members hold the Certified Investment Management Analyst designation, and 5% are in the process of getting the designation, according to Sean Walters, the CEO and executive director of the organization.

Getting the CIMA designation starts with a self-study component followed by a qualification exam, with a first-time pass rate of 55% and a cumulative pass rate of 60%, says Walters. While most candidates take a couple of years of study and pass the qualifying exam, it can be done in just a few months.

Once you pass the qualifying exam, you're eligible to attend a five-day course of study at the Aresty Institute of Executive Education at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. At the end of the five-day program, Wharton gives CIMA candidates an assessment, and those who pass are eligible to take the CIMA certification exam, which is administered three times a year. The entire process costs about $7,500, most of which is for the week at Wharton, says Walters.

Most IMCA members historically come from wirehouses, and IMCA does not advocate for its members, nor take an advocacy stance on the fiduciary issue. That has allowed it to continue growing without alienating either its traditional wirehouse constituents or the growing number of RIAs joining. As more CIMA wirehouse brokers go independent, the influence of CIMA on RIAs is growing.

Walters says about 55% of IMCA's 8,100 members are employed by a Big Four wirehouse, while 22% are either RIAs or dually registered as an IA rep and registered rep, and 15% are asset managers, wealth managers and wholesalers. The rest work for banks, regional B-Ds or trust companies. The fastest growing membership segment is RIAs, says Walters-the same advisors the FPA targets.

Along with the fact that obtaining a CIMA designation is much easier than getting a CFP, another factor that may make the CIMA approach appealing to independent advisors is the CIMA's direct approach to the business. Financial advisors get paid for investing, and investing is the focus of the CIMA program.

In contrast, financial planners have trouble getting paid for writing financial plans. That's because many of the people who are willing to pay for a financial plan are so wealthy that they don't need a plan; they'll never run out of money. Meanwhile, the people who do need a comprehensive financial plan, because they could indeed run out of money late in life, are too strapped financially to pay for a plan.

The other membership group that is gaining traction with independent advisors is the CFA Institute. To earn the CFA designation, candidates must pass three exams, which each take the average successful candidate 300 hours, and also have at least four years of work experience in the investment industry. It takes most CFA candidates two to five years to pass all three exams, according to CFAI, and it costs as little as $2,175 for the entire program. The CFA Program is a graduate-level credentialing program that links theory and practice with real-world investment analysis, valuation and portfolio management. Of the credentials for investment professionals, the CFA is widely regarded as the one most difficult to earn.

While the CFAI says fewer than 20% of those who start the program complete it, there are 100,000 CFAs worldwide and 54% of them are in the U.S. Of the 100,000, about 30,000 provide advice to private clients, according to Stephen Horan, who heads the CFAI's private wealth manager division.

Private wealth managers, Horan says, tend to focus on clients with between $1 million and $5 million in assets. Horan says the demise of defined-benefit plans and rise of defined-contribution plans has over the past 30 years created a greater need for advisors to high-net-worth individuals, and the need has accelerated as more baby boomers approach the end of the accumulation stage of their wealth and move into the distribution stage. Horan says another factor that brought more CFAs into the private wealth arena was the financial crisis of 2008. The crisis resulted in the layoffs of many CFAs and they have since moved into advising individual clients. "A lot of talented investment professionals were looking around saying, 'How will I use my skills?'" Horan says. "They see a need among private individuals."

The rise of the FSI, IMCA and the CFAI, and the FPA's concurrent slide in membership, may only be short-term trends. They may well be the effects of the recession. But financial planners should take note. Because the rise of these other groups may in fact be a signal that an underlying problem exists in the way financial planning is applied in business.

Financial plans have always been a loss-leader for independent advisors. Many advisors might opt to sell their services by emphasizing the holistic approach of a comprehensive financial plan or by giving away the plan or discounting its cost drastically as part of an ongoing portfolio management program. Or they might only offer "modular plans" dealing with one particular aspect of an individual's finances, such as college funding or retirement. The financial plan is offered because it is a sound approach, but most planners actually get paid for managing assets and not for financial planning.

Financial planning has been dominated over the past 15 years by high-minded entrepreneurs who have achieved success in their practice and who have good intentions but may not always be as practical as they could be when it comes to creating a business model that can be embraced by a wide range of professional advisors. The refusal of the CFP Board of Standards to give continuing education credit for sessions dealing with practice management, business and marketing is an example of how some decisions can shortchange planners by not preparing them for real-world planning applications in a business setting. It appears that advisors are increasingly turning not to the FPA for answers but going elsewhere to get the support they need.

Editor-at-large Andrew Gluck, a veteran financial writer, owns Advisor Products Inc., a marketing technology company serving 1,800 advisory firms.