It’s often been said that what’s bad news for the economy is good news for the gold market. This year, with chaos and global shocks in distressing abundance, gold went from meandering between $1,100 and $1,300 an ounce for years to over $2,000 an ounce within a matter of a few months.

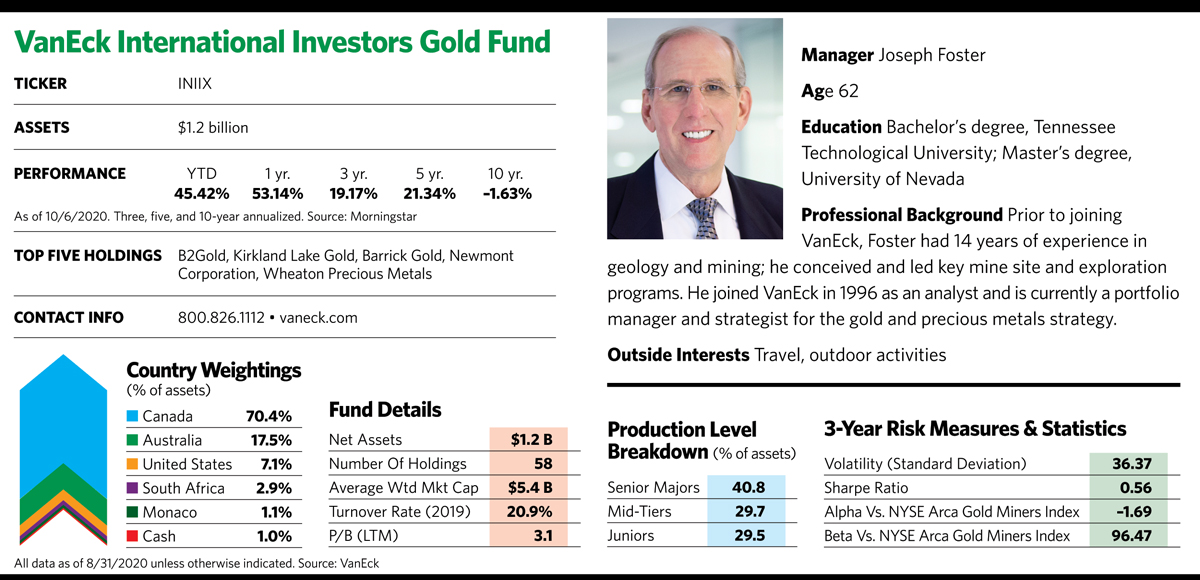

“Gold prices respond to systemic financial distress,” says Joe Foster, who manages the VanEck International Investors Gold Fund. “And there’s a lot of that out there now.”

Foster, a former geologist who made the transition to the investment side of precious metals in 1996, sees plenty of steam left in the current rally. “The case for investing in gold has not been this compelling in years,” he observes. “We believe current price trends suggest a long, sustained rally in gold, similar to the 2001-2008 secular rally. A price of over $3,000 over the next couple of years is reasonable in our view.”

Gold tends to do best in times of marked inflation or deflation, both signals of troubling times for the economy. Foster believes the pandemic is likely to depress economic growth and spark deflation in the near term. Without intervention, millions of Americans risk eviction by year’s end. Continued layoffs, high unemployment, the devastating impact on businesses and government budget shortfalls all point to an environment in which deflation thrives.

Other factors, like the weakness of the U.S. dollar, geopolitical uncertainty and continued rising debt levels at corporations add credence to that view. Negative real interest rates, which signal an economy desperately trying to right itself, is a positive for the perceived safe haven of gold.

Foster says the economic fallout from the pandemic is likely to continue at least through next year. “Things could start returning to normal with the wide availability of a vaccine,” he says. “But I think that’s a 2022 story.”

Further out, gold could also prosper once a recovery begins. At that point, inflation might rear up as the massive monetary stimulus being pumped into the economy to deal with the pandemic leads to rising prices. “The Covid-19 war might end with another cycle of unwanted inflation,” he says.

Amid all the tumult, supply and demand dynamics appear to favor the metal moving forward. Gold continues to be a scarce commodity, and the fact that there have been no significant new gold discoveries since 2016 only adds to its supply pressure. Demand for gold, however, has continued to rise as investors seek exposure and central banks add to their gold reserves. The increasing use of exchange-traded products backed by physical stores of gold offers another level of pricing support.

The Case For Gold Miners

Investors can ride the price of gold through several routes, including physical gold bullion, exchange-traded funds that track gold prices, or mutual funds and ETFs that track gold miners. While all are affected by changes in the price of gold, miners are historically more volatile and magnify the movement of gold prices both up and down.

Because the costs of mining are fixed, any price increase typically brings with it a boost to cash flow profits—and stock prices. Conversely, a price drop has a negative effect on all those things. This historical pattern held true in the upcycle for gold in 2020, when the VanEck Vectors Gold Miners ETF (GDX) was up 42% year-to-date as of mid-September. Over the same period, the VanEck Merk Gold Trust (OUNZ), which follows the price of gold, rose 28%.

Foster has more insight than most into the drivers that make for successful gold miners, or dismal failures. He moved to Reno, Nev., in 1982 to obtain a dual degree in business and geology at the state university’s graduate school. Upon graduation he found work at a local mine, just as Nevada was ramping up its mining industry, and stayed there for a decade. Looking for a life change, he answered an ad from VanEck for a gold mining stock analyst in 1996, got the job, and moved to the New York area.

Although he hadn’t invested in a single gold mining stock before becoming an analyst, his engineering knowledge proved to be a strong asset in evaluating companies. “There are three key things from the technical side: the geology of deposits; how to get gold out of the ground; and metallurgy, or how to extract gold from a rock,” he says. “I learned the investment side on the job.”

He also learned about some of the risks involved in investing in global gold mining companies. An important one is geopolitical risk, which measures the impact of governmental policies and regulations on the business. Such risk has kept the fund out of companies with operations in several Latin American and African countries, as well as China and Russia. Even in the U.S., state-by-state regulations can vary widely and influence investment decisions. “Nevada has a long-established mining industry. It’s the second-largest industry in the state, and it’s a strong part of its heritage. California, on the other hand, has very restrictive laws that are hostile to mining companies.”

He says that companies have been successful navigating through political turmoil. He points to fund holdings B2Gold Corp. and Barrick Gold Corp., which both have mines in Mali. Even with a military coup and a pandemic in the country this year, their production remained steady and operations in Mali did not shut down. The mines are located far from the capital, where the unrest is taking place, and the companies have become adept at nurturing government relationships. “No matter who is in power in Mali, everyone knows it is in the country’s best interest to keep the gold mines running,” he says.

Beyond politics, mining companies also have environmental and social issues to contend with. Many investors think gold miners fall short in those areas, but Foster says that isn’t the case. “Gold miners must have reclamation plans for mines, and they operate under a huge number of environmental regulations,” he says. “They are typically located in smaller communities, where they play a pivotal role in providing health care, job training and employment.”

Although the stocks of gold miners have had an extraordinarily strong run this year, Foster does not think they are overvalued. In past rallies, he says, mining stocks have experienced roughly double the percentage increase in the price of gold. The current rally falls short of that pattern. Price-to-cash flow numbers, a key measure of how well a gold mining company is doing, have also fallen well below the levels of previous gold rallies.

The industry is also in better shape than it was just a few years ago. Many companies have lower debt and better financial discipline than they did a decade ago, and Berkshire Hathaway’s new stake in Barrick points to increased interest among general investors. “Barrick and many other companies we invest in have every intention of maintaining their discipline by controlling costs, controlling debt and using conservative gold price estimates as the benchmark for evaluating capital projects,” Foster says.

The industry is beginning to bifurcate between dividend-paying companies with high quality, low-cost mines and those with lower quality projects and higher risks. “Until there is confirmation that higher gold prices are here to stay, it seems too early in this cycle to speculate on companies that aren’t maintaining the discipline learned from the mistakes of the last cycle.” Chief among those mistakes, he says, was basing new mining project profitability on high gold prices that prevailed when those projects started. Because it takes up to seven years to get a mine running, such assumptions can be disastrous for companies if prices drop.

“We are forecasting gold prices of over $3,000 per ounce, and if correct, all companies will win,” he says. “However, it would be reckless to build a mine and risk a company based on such forecasts.”

Instead, the fund gravitates toward companies that are undertaking projects based on more realistic assumptions, and that have the financial stability to withstand a price drop. It divides its 58 holdings into major, mid-tier and junior mining companies. The major group, which includes Newmont Corp. and Barrick, are some of the more familiar names in the industry. They’re able to generate substantial cash and increase dividends, especially with gold prices at current elevated levels.

The mid-tier group, which accounts for around 30% of assets, consists of companies with smaller mining operations that are looking to expand their footprint through exploration and discovery of new gold deposits. B2Gold falls into this category.

The junior group, which makes up another 30%, consists of companies in the nascent stages of drilling and exploring. Fund holding Liberty Gold, a Canadian exploration and mining company, is in the process of redeveloping a local gold mine in southeastern Idaho that was shut down in the 1990s when prices dropped.

If the tumult of 2020 extends into next year, a similar scenario may not unfold for a while.