Whether a midstream energy mutual fund is taxed as a C-corporation or a regulated investment company (RIC) can have a meaningful effect on its portfolio composition, performance characteristics and after-tax returns. In the current market environment, we believe RIC funds offer structural advantages due to their better flexibility to invest across the broad midstream universe, greater tax efficiency and potential for increased total return.

According to Morningstar, more than 70 percent of the assets in open-end mutual funds devoted to midstream energy investments are in funds taxed as C-corps. These C-corp funds often appeal to income-seeking investors, but they have several drawbacks not found with RIC-structured funds. We believe these considerations are particularly important today for three key reasons, amid improving midstream fundamentals and a shift in business models away from master limited partnerships (MLPs).

#1 C-Corp Funds Tend To Own A Small Percentage Of The Midstream Universe

C-corp funds typically seek to maximize income and distributions paid, and in doing so they tend to own primarily MLPs. C-corp funds can own securities of midstream corporations, but they usually limit these holdings as these investments generally offer lower yields and add inefficient layers of taxation.

While C-corp funds’ focus on MLPs may not have been an issue several years ago, MLPs are now a shrinking slice of the midstream universe—a trend we expect will continue.

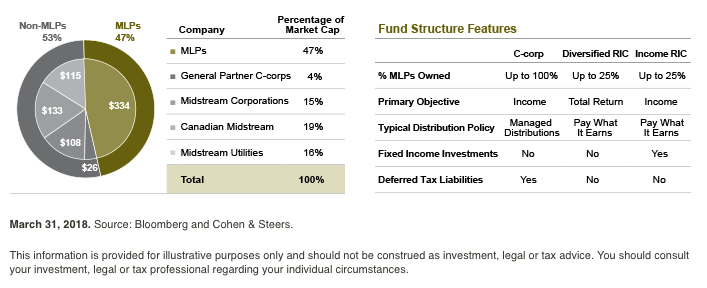

MLPs represent 47 percent of the midstream sector (Exhibit 1), down from 53 percent at the end of 2013. Increasingly, the sector consists of corporations, including general partners that manage the operations of MLPs, companies that own midstream assets, and Canadian-listed energy infrastructure companies. C-corp funds may therefore be underinvested in potentially attractive, non-MLP midstream opportunities.

Post corporate tax reform, we believe midstream companies will continue to move away from the MLP structure, as lower corporate taxes diminish its relative advantage. In addition, the recent Federal Energy Regulatory Commission proposal further reduces the incentive to utilize the MLP structure for companies that own certain regulated interstate pipelines.

RIC funds tend to have a broader mix of holdings, with no more than 25 percent of assets in MLPs. As a result, they tend to have lower yields than C-corp funds, but generally own more growth-oriented investments, potentially making RIC funds better total return vehicles.

RIC funds also have appeal to income-seeking investors due to distributions being partially tax deferred. RIC fund distributions generally consist of 50–80 percent return of capital, with the balance typically treated as qualified dividend income that is taxed at the long-term capital gains rate.

In essence, a RIC fund typically offers a similarly high tax-deferred rate on distributions as a C-corp fund invested entirely in MLPs—all while accessing a broader investment universe to achieve its goals.

What distinguishes different types of RIC funds is what they do with the other 75 percent of the portfolio not invested in MLPs. Some limit their non-MLP holdings to general partner and other U.S. midstream corporations—meaning that the remaining 75 percent of their holdings are invested in just one- quarter of the midstream universe. Still other RIC funds include a substantial fixed income allocation, potentially boosting yield but increasing their interest-rate sensitivity and foregoing possible equity returns in the process.

Diversified equity RIC funds invest across the entire midstream equity space and, in our view, provide the greatest flexibility to generate strong total return potential in midstream equity investments.

#2 C-Corp Dividends May Not Be What They Seem

Most C-corp MLP funds employ managed distribution policies and have maintained high payouts in recent years—despite substantial distribution cuts across the MLP market—by returning capital to shareholders.

The Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP), an exchange-traded fund, can serve as a useful proxy for the MLP industry. Since the end of 2015, AMLP’s dividend per share has declined by nearly 31 percent, as many MLPs have cut distributions to retain capital to fund their growth. AMLP’s cuts stand in stark contrast to most C-corp funds, where distributions have remained largely unchanged during the past few years (Exhibit 2).

In our view, most C-corp funds do not have the underlying earnings power to support their current payout—and ultimately, we believe, these funds will elect to cut their dividends.

Many RIC funds, including Cohen & Steers MLP & Energy Opportunity Fund (MLOAX), have pay-what-it-earns distribution policies. Such policies may entail some volatility in the amount of distributions paid each quarter, but in our view represent a healthier way to invest in the asset class. Having gone through the process of cutting dividends, we believe this will allow the RIC funds to continue to participate in the midstream growth story going forward.

#3 C-Corp Funds May Suffer From Stealth Taxes

Even factoring in lower corporate tax rates as a result of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, C-corp funds remain at a tax disadvantage relative to RIC funds. As taxable entities, C-corp funds must record the future tax obligation on any unrealized gain, including increases in an investment’s value and return-of-capital distributions. Investors generally overlook this tax—recorded as a deferred tax liability (DTL)—as it is subtracted from the fund’s net asset value (NAV), resulting in a higher gross expense ratio and reduced performance.

These DTLs may result in double taxation—once at the fund level on unrealized gains and again at the individual level on any realized gains when the shares are sold, in addition to taxes on ordinary income distributions. The added DTL obligation may reduce an investor’s after-tax return in a rising market.

In a declining market, unrealized losses should theoretically generate deferred tax assets (DTAs) in C-corp funds. However, accounting rules make it difficult for mutual funds to support net DTAs, since they are not operating companies, and many funds are not allowed by their auditors to book the entirety of the DTA. Due to the 21 percent corporate tax rate, over a full cycle, many C-corp funds with net DTLs may capture only 79 percent of the market’s upside and most, if not all, of its downside.

Exhibit 3 shows how the taxes paid due to DTLs on unrealized gains may reduce a C-corp fund shareholder’s NAV by 21 percent. For an individual in the top tax bracket, selling the investment could potentially result in a total tax rate of as much as 37 percent, compared with 20 percent for a RIC fund.

RIC funds are not taxable entities and thus do not accrue DTLs from unrealized gains. Instead, income and realized net long-term capital gains pass through the RIC to the investor. As a result, RIC fund expense ratios do not include tax adjustments. A RIC fund investor is only taxed on realized income and capital gains, allowing them to keep more of what they earn.

The RIC Advantage

We view RIC funds as superior total return investments and C-corp funds primarily as income vehicles. By investing more broadly across the midstream universe, RIC funds have historically achieved better returns with only slightly greater volatility than the more MLP-focused C-corp fund universe.

In our view, the current environment of improving midstream energy industry fundamentals and rising interest rates is likely to favor total return strategies over income—and consequently, RICs over C-corps.

Tyler Rosenlicht, senior vice president, is a portfolio manager for Cohen & Steers' infrastructure portfolios with an emphasis on MLP and midstream energy strategies.