We are reminded of Ben Graham’s Mr. Market analogy. In his analogy, the stock market is like having a business partner (Mr. Market) who offers to either buy or sell his half of the business to you based on how the business is doing. When times are rough, he sets a very low price because he is afraid you will dump the whole thing on him. When times are good, he sets a very high price because he is afraid you’ll buy the other half away from him. Mr. Market volunteers to set the price each day, just like the stock market does, but you don’t have to act on it.

We like to combine value buying, made available by Mr. Market, with the second tenet of our investment discipline. We want to own businesses on behalf of clients for a long time. We act as if we own the whole business, despite only owning a small part of it. Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger have been the leading proponents of this part of our discipline. Buffett says, “Own shares of a company as if you’d be fine if stocks didn’t trade for 10 years.”

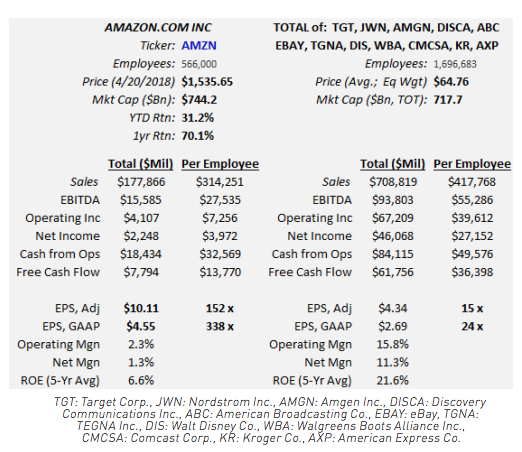

With those thoughts in mind, look at the contrast created in the following statistics:

For the same money that Mr. Market demands to buy the entire Amazon Corporation, you can buy a basket of 12 companies we own. We chose the list based on companies that are being treated very poorly by Mr. Market because of the “existential threat” coming from technology companies, placed in the retail, grocery, media, pharmacy and health-care industries. These companies have met our eight criteria for common stock selection, which means they have measurable qualities that have historically led to durability and future success. We like them even though Mr. Market doesn’t.

If a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, Mr. Market is laying an incredible bird in our hand. Our basket of owned companies has nearly four times as much in sales, 16 times as much in operating income and 21 times as much of net income. Amazon has generated a five-year average return on equity (ROE) of 6.6 percent versus 21.6 percent for our companies. Here is what Charlie Munger said about long-duration equity returns based on ROE:

“Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns six percent on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you’re not going to make much different than a six percent return—even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18 percent on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with one hell of a result.”

We have no way of knowing whether Amazon will succeed enough in the future to justify buying it today and holding it for a long time. We do think we know that our basket of companies is offered at reasonable/bargain prices in relation to the S&P 500 Index. We also believe that some part of them will survive and prosper with high returns on equity for a long time. Based on Munger’s teaching, if they do survive and prosper, we could end up with “one hell of a result.” Here are his thoughts on tortoise stocks versus hare stocks:

“It is occasionally possible for a tortoise, content to assimilate proven insights of his best predecessors, to outrun hares that seek originality or don’t wish to be left out of some crowd folly that ignores the best work of the past. This happens as the tortoise stumbles on some particularly effective way to apply the best previous work, or simply avoids standard calamities. We try more to profit from always remembering the obvious than from grasping the esoteric. It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.”

Lastly, our best way of thinking about this investment contrast is imagining that we were the wealthiest person on earth and we could afford an investment of $740 billion. Would we buy the whole company called Amazon or would it be obvious to us to buy the other 12 companies that fit our eight criteria for close to the same amount?

William Smead is CIO and CEO of Smead Capital Management.