Over the last year, natural catastrophes and political upheaval have brought a barrage of woes to the municipal bond market. A hurricane that brought widespread devastation to Puerto Rico made many wonder whether the U.S. jurisdiction would ever be able to pay off its bonds. President Trump’s mission to destroy the Affordable Care Act, threatening coverage for millions of people, brought uncertainty to hospital revenue bonds. And efforts to lower individual income tax rates, if successful, threaten to make the tax-free status of municipal bonds less attractive.

Over the last year, natural catastrophes and political upheaval have brought a barrage of woes to the municipal bond market. A hurricane that brought widespread devastation to Puerto Rico made many wonder whether the U.S. jurisdiction would ever be able to pay off its bonds. President Trump’s mission to destroy the Affordable Care Act, threatening coverage for millions of people, brought uncertainty to hospital revenue bonds. And efforts to lower individual income tax rates, if successful, threaten to make the tax-free status of municipal bonds less attractive.

Even for a market veteran like John Miller, managing director and co-head of fixed income at Nuveen Asset Management, it’s hard to remember a time when so many balls have been in the air. “There are more potentially impactful events and issues to watch for now than I’ve seen in my 24-year career in the municipal market,” he observes.

Yet municipal bonds have proved to be extraordinarily resilient this year, performing better than many other corners of the fixed-income markets. As of September 30, the broad municipal bond market was up 4.66% year to date, well above the 3% return for the taxable U.S. aggregate bond market. High-yield municipals fared even better, rising 7.22% over the period. Without beleaguered Puerto Rico bonds weighing it down, the latter group would have risen 10.35% over the period.

Much of that performance is attributable to a bounce-back from a late 2016 downturn, when investors believed the newly elected president would lower tax rates, destroy the Affordable Care Act and make other moves that could hurt munis. As 2017 has progressed, investors are coming to realize that the strongly divided Congress and unpredictable leadership could water down those changes—if they happen at all.

“Even if some of Trump’s goals are accomplished, the negatives for municipal bonds are not likely to be as bad as many people originally thought they would be,” says Miller.

One of the biggest questions hovering over the market now is the prospect for lower individual and corporate tax rates, which could hurt municipal bonds by making their tax-exempt status less attractive. Miller points out that, historically, the relationship between tax rate changes and municipal bond prices is far from solid. During the Reagan and George W. Bush administrations, when taxes were cut, municipals still produced healthy gains. Conversely, the increase in taxes under former President Obama did not benefit municipal bonds.

What’s more, the current proposed Republican tax plan isn’t as onerous as it might appear at first glance. Because it would not lower the top personal income tax rate much below the current rate of 39.6%, any change would not likely have much effect on demand for tax-exempt bonds. Additionally, Miller says the 3.8% Medicare surtax on investment income for high earners, which doesn’t apply to municipal bond income, “will likely stick around.” And while the Republican tax plan would also eliminate all itemized deductions except those for mortgage interest and charitable contributions, it does not take aim at the tax exemption of municipal bond interest.

While the personal income tax rate would not decline significantly, the corporate tax rate would fall from 35% to 20% under the Trump proposal. That change could lead to a reduction in demand for municipal bonds from banks and insurance companies.

Ultimately, says Miller, legislators are more likely to settle on a corporate tax rate in the 25% to 30% range. While a lower corporate tax rate might make municipals less attractive to some companies, “it’s unlikely that they would sell off a well-performing municipal bond portfolio because of it,” he says. “The most important thing is that municipals stay tax-exempt, which is the case in the initial tax plan.”

The elimination of the deduction for state and local taxes, another possibility under the proposal, would make bonds that are exempt from state taxation more attractive for investors in high-tax states. For a taxpayer subject to California’s 11.3% tax rate (if the federal rate were 35%), eliminating the deduction would increase the taxable-equivalent yield of a 2.00% California-exempt bond from 3.47% to 3.72%.

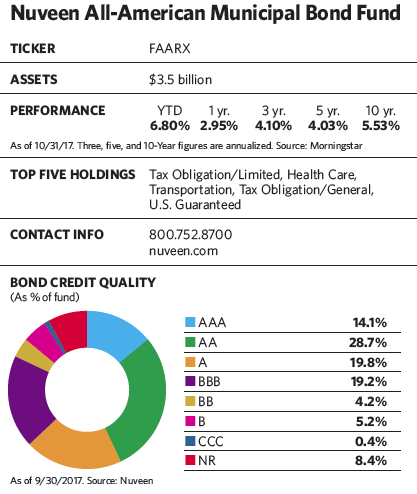

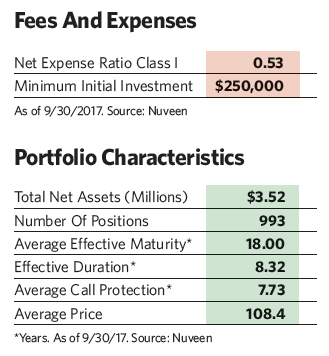

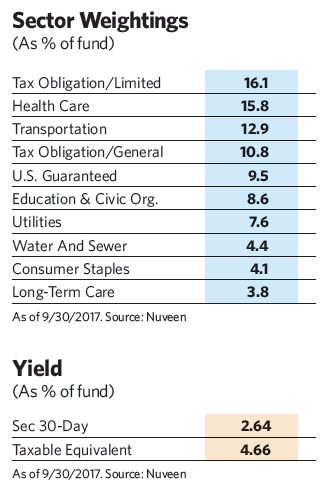

Meanwhile, after-tax yields are attractive at current tax levels. The highest marginal tax rate is currently 43.4% (which includes a 39.6% federal rate plus a 3.8% Medicare tax on investment income). For an investor subject to that rate, a taxable investment would need to yield 4.42% to produce as much after-tax income as a municipal bond investment yielding 2.5%. As of September 30, Class I shares of Nuveen’s flagship municipal bond mutual fund, the Nuveen All-American Municipal Bond Fund (FAARX), yielded 2.64%, creating a taxable equivalent yield of 4.66%.

Health-care bonds, whose interest payments are made from revenue generated by hospitals and other health-care facilities, are another question mark. Miller points out that while attempts to repeal the ACA are a serious threat to the short-term stability of the individual market, various court cases are in the works to limit the president’s ability to eliminate it, and Congress has started to look for bipartisan fixes to water down the cuts. Nonetheless, he does not discount the possibility of some disruption to the individual markets.

But the potential effect on most hospital credits could be minimal, he says. Currently, only 6% of the population is covered through the individual market, and only 4% purchase their insurance on the exchanges. The demographic that currently gets insurance through these plans has never been a vital source of revenue to most hospitals, which historically rely mostly on a combination of Medicare, employer-based commercial insurance and Medicaid for roughly 80% to 90% of their revenues.

Even amid the legislative bickering over the ACA, Miller continues to favor the health-care sector, which makes up roughly 16% of the Nuveen All-American Municipal Bond Fund. He says the hospitals provide strong recurring revenue from essential services. Also, Nuveen’s deep analyst bench evaluates hospital issuers based on criteria such as the demographics in their areas, the insurers in their markets and the hospitals’ debt burdens. These criteria ensure that the fund will stick with creditworthy issuers.

On the downside, there’s been a spike in municipal market defaults, which have climbed from $2.3 billion in 2015 to $27 billion in 2016 and $10.8 billion in the first half of 2017. The lion’s share of defaulted debt comes from issuers in Puerto Rico, which filed bankruptcy-like petitions in May 2017. Miller says the U.S. territory’s difficulties have been telegraphed and evolving since 2013, the year that the Nuveen fund exited the troubled market. “Massive out-migration, damaged infrastructure and crippled tax collection after the hurricane have made a bad situation worse,” he says.

Despite the current problems faced by muni bonds, there are a number of classic arguments to be made for them. For instance, they have less volatility than other corners of the fixed-income market. Over the last 10 years, the standard deviation for U.S. Treasury securities with 10- to 20-year maturities was 8.9, while it was 10.72 for high-yield corporate bonds. Over the same period, the standard deviation was a much lower 4.53 for the broad municipal market and only 7.49 for the high-yield muni segment.

Although the Nuveen fund doesn’t have any bonds mired in the Puerto Rico mess, it still skews more toward below-investment-grade bonds than the municipal bond indexes do. The fund can invest as much as 20% of its assets in securities that are either not rated or rated below investment grade, and according to its latest fact sheet it has about 18% in such securities. By comparison, the iShares National Muni Bond ETF (MUB), the largest muni bond ETF, has virtually no exposure to below-investment-grade bonds. Miller says that in a low-yield environment, lower-rated and non-rated bonds go a long way toward boosting returns, and he points out that defaults, even for lower-rated municipal bonds, are extremely rare. He adds that because the firm’s research department analyzes each credit extensively, the fund has not had a bond in its portfolio default “for many years.”

In addition to investing in carefully evaluated but lower quality corners of the credit spectrum, the Nuveen All-American fund also emphasizes parts of the yield curve that its manager believes appear most attractive. Right now, yield spreads relative to taxable bonds vary but are more attractive at the longer end of the yield curve. As of September 30, the 10-year “AAA”-rated municipal bond yield was 86% that of Treasury securities with the same maturity, slightly better than the 84% historical average since 1984. The yield on longer-term municipal bonds was about even with that of long-term Treasurys. Usually, it is somewhat lower.

To pick up extra yield, the Nuveen fund has a higher stake in higher-yielding, longer maturity bonds than it does in indexed products. Its 8.32-year duration is longer than the six-year duration of the iShares National Muni Bond ETF and the 5.7-year duration of Vanguard’s Tax-Exempt Bond Index mutual fund (VTEAX).

The strategy of taking a stake in well-chosen, lower-quality credits and extending duration has paid off thus far. As of September 30, the Class I share returns of the Nuveen fund were in the top 5% of Morningstar’s municipal long bond category over three years, in the top 4% over five years, and in the top 1% over 10 years.

“With low interest rates, many issuers call or pre-refund their bonds, so index durations are shorter than they’ve been in the past,” Miller says. “That means lower yields. We’re combating the impact of calls and pre-refunding in our funds with active management.”