What Is Real?

In times of inflation, real rather than nominal values grow far more important. How well has a price or return delivered for you, after taking inflation into account? In markets, it’s real rates that most matter. But how exactly do you measure reality?

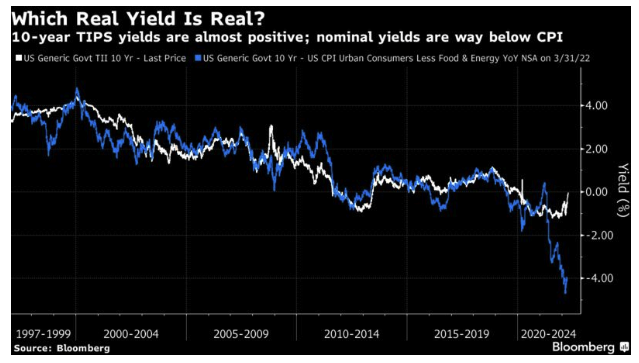

The issue matters because real yields have stayed incredibly low for much of the last year as nominal yields have risen. With real yields low, financial conditions hadn’t tightened so much. But that is fast changing. At the time of writing, the 10-year TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) yield is above zero. True, it’s still only positive by less than one basis point, which is scarcely restrictive, but the speed of the adjustment in the last few weeks has been impressive. It challenges the assumption that real yields will forever stay accommodative.

However, there’s an argument that TIPS embody unrealistic expectations for inflation. A brutally simple version of the real yield would subtract the current rate of inflation from the nominal yield. Over time, this has been very similar to the TIPS yield. But no longer. The nominal 10-year yield is four percentage points lower than core inflation (and even further below headline inflation):

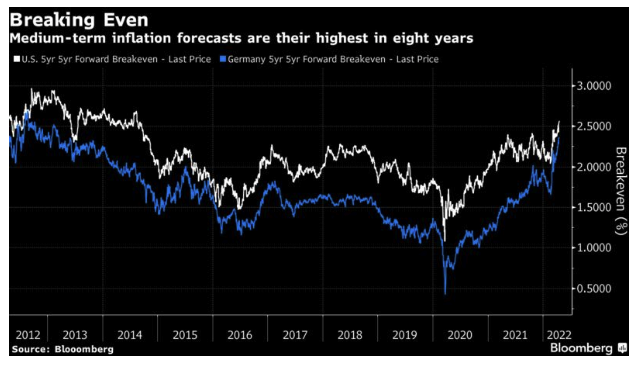

So are we paying a real interest rate for long-term money or not? Another abstruse corner of the bond market muddies the picture further. The Federal Reserve’s favorite measure of market-based inflation forecasts is the five-year/five-year breakeven, which captures expected average inflation for the five years starting five years hence. Like the 10-year TIPS yield, this has been a source of comfort throughout the inflation scare of the last year. Inflation expectations on this basis have remained steadfastly under control. Whatever the fears in the present, this measure has said the market is confident that the Fed can rein in the price pressures over the next five years.

But that is no longer so comfortable. This breakeven is now at its highest since 2014. The level isn’t scary, but the fact that it has now plainly broken out of the low-inflation regime of the post-crisis era is disquieting:

Even more disquieting is the speed with which the market has abandoned its fixed assumption that German inflation had been anesthetized. It’s coming around now, with the German five-year/five-year breakeven suddenly almost equal to the U.S. If market forecasts can change so quickly, does that mean we should ignore them? Quite possibly. But however measured, a lot is riding on continued negative or very low real yields. To quote Jim Reid, financial historian at Deutsche Bank AG:

I’m not convinced the bond market’s prediction of future inflation is particularly useful. Spot real yields should rise from here as spot inflation falls, but I’m still not convinced inflation falls anywhere near enough over the next couple of years for real yields to get anywhere near positive. I’m also still convinced real yields on this measure stay negative for the rest of my career due to financial repression. If I’m wrong (maybe due to nominal yields rising more than I think and inflation falling faster), run for the hills given the global debt pile.

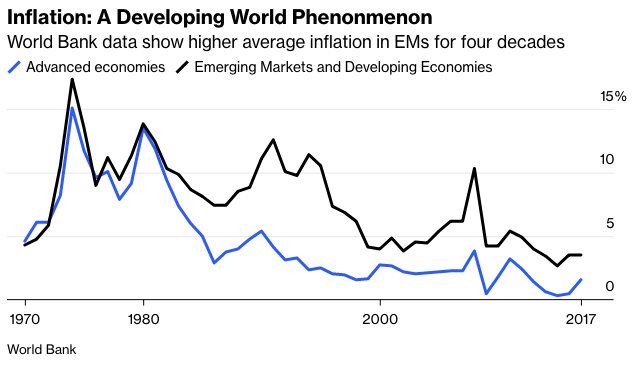

Emerging Inflation

If these assumptions are difficult, an even bigger one is coming in for reassessment. For about as long as economists have made a serious effort to measure them, emerging economies have been prone to higher inflation than the developed world. The following chart is based on data from a World Bank book and go up to 2017:

That assumption no longer holds good. This chart compares Bloomberg’s measure of average consumer price inflation in emerging economies with U.S. headline inflation:

Even though emerging markets currently have prices under better control, their central banks have to remain far more vigilant than their developed-market counterparts, so they have already hiked rates. That raises their risk of stagflation. It should strengthen their currencies, which will help combat inflation but render them less competitive. And it’s in the world of foreign currency that the rubber will hit the road and these assumptions and contradictions will be resolved.

Something’s Gotta Give: Foreign Exchange Edition

There is no compromising in the world of currencies. Each currency pair is in effect a zero-sum game, with some traders winning and others losing by the same amount. Confused and divergent views of inflation and real yields in different countries must be reconciled into one exchange rate. The forex market will probably determine whether the current extraordinary conditions tip over into crisis.

Something in currencies has to give, thanks to the extreme divergences in monetary policy. This summary is from Larry McDonald of Bear Traps Report LLC:

The current policy divergence between the a) PBOC (cutting rates, 530B yuan additional liquidity), b) the ECB—wind down net asset purchases this quarter / set for a 2H rate hike—QT out of the question now, c) BOJ aggressive balance sheet expansion, d) Fed promising 9-12 rate hikes looking out a year with QT aggressively involved. This type of insane monetary policy divergence will clearly break something, that is certain—unsustainable.

This is strongly worded but not unreasonable. Central to everything, as ever, is the dollar. Following the popular dollar index, which compares the dollar against a basket of major developed market currencies, there is still much further to go. It has recently gone above an index level of 100. Excluding very brief spikes during the first Covid shutdown of 2020 and in the immediate aftermath of Donald Trump’s election in late 2016, it hasn’t been at this kind of level in almost two decades. However, prior history in the period since the dollar’s peg to the gold price was removed in 1971 suggests that the dollar could appreciate much more. The logic of current divergent monetary policies is that it should do exactly that:

Meanwhile, the logic confronting investors is that the yen can only get weaker. That makes the “carry trade” safe once more. Popular in the years before the Great Financial Crisis, when it contributed greatly to excessive speculation, the yen carry trade involves borrowing in the Japanese currency at low interest rates and parking in a currency that offers higher rates. It works unless the yen strengthens. And so money is pouring into countries like Colombia, Australia and particularly Brazil, where rates are expected to rise. Countries backed by commodities should be more durable in an inflationary environment in which raw materials prices are rising:

The all-time high for the Aussie dollar carry trade, and the near-high for the Brazilian real trade, suggest that things cannot be taken much further before something breaks. The Bank of Japan remains determined to stay dovish until it can force inflation up to 2%. The weak yen presently stands to drive up the price of imports to Japan very significantly. Westpac publishes a “real effective exchange rate” comparing the yen to its trading partners’ currencies, and taking into account different inflation rates. All else equal, the fact that Japan has lower inflation than almost everyone else should cause the yen to strengthen. That hasn’t happened:

Given the sharp fall for the yen since the index was last calculated at the end of last month, we can say with some confidence that the currency is at record weakness in real terms. Is that really what Japan desires, and will the rest of the global economy withstand it? Or will it force the BOJ to change course?

Then there’s the euro. A natural benchmark is the Swiss franc, geographically at the center of Europe and long regarded as a hard currency. The franc spiked against the euro during the sovereign credit upheavals in the summer of 2011, and again in early 2015 when the Swiss National Bank abandoned its attempt to keep its currency from appreciating too far. The franc is now approaching those levels again, and nearing parity, a point that could have a big psychological impact both in Switzerland and in the EU:

Again, can investors keep piling on to a trend that seems to be growing over-extended, and can the central bankers and politicians involved tolerate it? It’s questionable. So is whether the ground rules remain the same as they used to be.

A decade ago, when Brazil’s finance minister complained of “currency wars,” he meant that carry trades were pushing the real up and making his country less competitive. In that environment, the “war” was to have as weak a currency as possible to fight deflation. Now, with inflation the enemy, the “winners” will be the currencies that strengthen the most. To cite Vincent Deluard, investment strategist at StoneX Group Inc.:

When the economy is at full capacity, the only way to increase supply is to import: Strong currencies are needed to lower commodity bills and steal trade partners’ output. The winners of the currency wars of the 2020s will be the currencies which can rise the fastest.

On that basis, the U.S. and China seem well placed, while potential winners, Deluard suggests, include the Australian, Canadian and Singaporean dollars, the Swiss franc and the Norwegian krone. Things don’t look great for Japan or the eurozone.

There’s space to argue about real yields and their definition. But the one thing we know for sure is that the contradictions in currency markets will be resolved, somehow or other.

Reopening: Bad For Some

For all the excitement in the fixed income world, stocks had a good day. Then the market closed, and Netflix Inc. announced its results for the first quarter. For the first time in more than a decade, its number of subscribers had declined (slightly) from the previous quarter. Cue carnage.

In after-hours trading, the Netflix share price came down more than 25%. This is the second quarter when results that didn’t boost hopes for further revenue growth prompted a collapse in the share price. This is more about valuation than sales. If we look at Netflix’s price/prospective sales ratio, the last decade has been a story of ever-greater optimism expressed through valuation, and then a sudden return to reality. The line indicates where the Netflix price/sales ratio will be now, if the after-hours share price holds up.

What conclusions can we draw? First, it’s at least good news that this is tangible evidence of reopening post-Covid; very slightly fewer of us are spending money on streaming videos. Second, it tends to confirm the folly that many investors were pricing stocks that did well out of the pandemic on the implicit assumption that lockdown behavior would continue in perpetuity. Netflix was a great place to shelter, but it was never a great idea to assume that its growth would continue.

Third, the extent of the crash in the share price for results that aren’t that bad shows just how much of Netflix’s value was locked in the future. It’s a classic long-duration stock. That makes it sensitive to changes in interest rates, and it’s also very sensitive to slight changes in future growth assumptions.

Fourth, we’re now seeing one of the fallacies behind FANG investing brought ruthlessly to light. Each of the big internet platforms has been priced as though it will achieve dominance, but in fact many of the FANGs compete with each other; Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. are trying to get a share of Netflix’s streaming revenues, Apple and Meta Platforms Inc. are in open conflict, and so on. They can’t all simultaneously achieve the dominance that is possible for each individually. Any day now, we can expect the chatter to get going over who will buy Netflix and for how much—and that will pose a fascinating question for the antitrust authorities. Apple and Amazon would both be logical buyers, but should they be permitted to make such an acquisition?

Finally, the “no skidmarks” way the share price has twice fallen vertically (borrowing a phrase from Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts LLC) is concerning. There is a lot of hope expressed in valuations, and the slightest challenge to that hope means instant crash, with no attempt to squeeze the brakes first. It’s not encouraging.

Survival Tips

On the subject of reopening, it continues apace. Last night, I had the pleasant duty of chaperoning my daughter to Radio City Music Hall to see the New Zealand songstress Lorde in concert. She is indeed rather wonderful—a very talented songwriter, with a Dali-esque set, and a straightforward and unpretentious way of presenting herself. This is what she was like as a teenager back in 2013. Here she is from 2019, and from last year.

As for the wisdom of being in a packed indoor place: Most, if not all, the rest of the crowd were much younger than me and had less to worry about from Covid. Very, very few were masked while dancing and singing along to the music. The great majority did put on masks unbidden to get out of the building, which involved packing together in some narrow stairwells. It all made sense. And it does feel like a relief, albeit a transgressive one, to be back in a crowd of people.

It also looked like it was great fun to be at Coachella last weekend. And I would have loved to be in New Orleans for what looks like a cathartic return to the stage by Arcade Fire. Yes, we all need to get out more. And now we can.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.